Assignment: Write an application that interfaces with an input and/or output device that you made, comparing as many tool options as possible.

I know how to program (that feels weird to say after feeling like an impostor in a computer science PhD program), so this week I decided to make my life more challenging than it had to be.

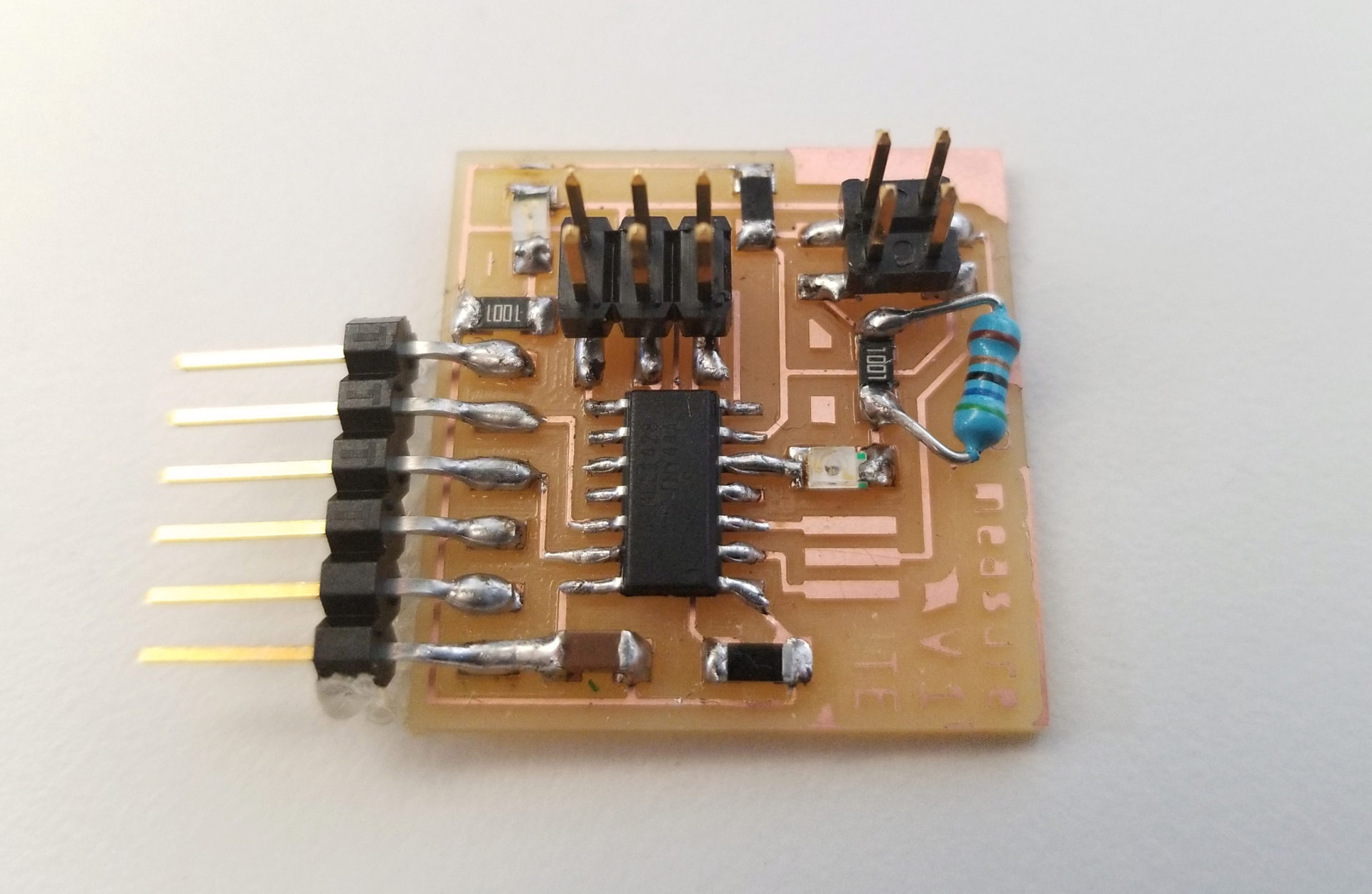

Before the code, a small hardware aside. Last week I had an issue with a resistor being to large. This week, I didn’t want to venture out in the cold to get a different SMD resistor from the physics lab. So I took the hacky route and just soldered on a breadboard resistor, making sure I didn’t short out anything else on the board. It’s not elegant, but it made it a lot easier to play my Flappy Bird game. (I’m still terrible at it, but now I can’t blame the LED power.)

Racket

The first thing I decided to do was invoke masochistic nostalgia and attempt to create an interface in my first programming language: Racket. I haven’t touched functional programming since I graduated from undergrad and stopped TAing Northeastern’s intro CS class.

Luckily, Racket has a library that makes it easy to interface with serial ports: libserialport. In addition to install DrRacket (the IDE for Racket), I installed the libserialport module for Racket (raco pkg install libserialport in my terminal) and the Linux library (sudo apt install libserialport-dev).

From there, it was surprisingly easy to connect to the serial port and read bytes from it out to the console. I pulled out some code back from when I took this class as a sophomore in undergrad to remember how to do some basic functionality. I’ve got to say, I was really good at documentation back then (probably because we were heavily graded on it and I was a goody two-shoes). I also looked at Neil’s Python hello world interface code from last week to understand how to interpret the incoming information from the serial port. As a sanity check, I read out 32 bytes from the port:

#"\1\2\3\4\326\3\1\2\3\4\327\3\1\2\3\4\326\3\1\2\3\4\327\3\1\2\3\4\326\3\1\2"

Awesome. Then I need to convert these into integers. My approach to this turned out to be kind of hacky, since there isn’t a nice built-in function to convert a byte/char to an integer, like the ord() function like in Python. So I made my own.

;; byte->integer : Byte -> Integer

;; Convert a byte to an integer

(define (byte->integer b)

(first (bytes->list b)))But I’m not gonna lie, it took me a lot of trial and error to get there.

The next problem is reading only the current data. At first, I was just always reading the next bytes in the input buffer. But since I’m not calling my read function at 9600 baud, it falls stupidly, uselessy behind really quickly. I needed a way to flush the input buffer in the serial port when I start checking for a value so I’m looking at fresh data to get a reading. I scoured the documentation and failed many ways before eventually resorting to StackOverflow. Lo and behold, StackOverflow delivered in the time it took for me to eat my lunch. I hadn’t missed something fundamental; it is actually kind of a pain to do this. The approach is to create a really large local buffer and read values from the input port into this buffer until the input pipe is empty.

(define BUFFER-SIZE 20000)

;; drain-port: InputPort -> InputPort

;; given a port, allocate a buffer of size 'BUFFER SIZE' and

;; repeatedly read available bytes or specials until 0

;; bytes are available.

(define (drain-port port)

(define buf (make-bytes BUFFER-SIZE))

(let loop ()

(define try-read (read-bytes-avail!* buf port))

(cond [(or (eof-object? try-read)

(and (number? try-read) (= try-read 0)))

port]

[else

(loop)])))Those were the two really challenging pieces of the puzzle. From there, creating the interface with the universe and draw packages was relatively straightforward; I just had to look back at my undergrad problem sets to remember how. I kept it simple here. Like Neil’s Python code, I displayed a bar showing the 10-bit value of the sensor. Then I added a button to save the current value and displayed these saved values.

Does this serve any purpose whatsoever? Nope! But I’m pretty proud of myself for remembering how to do basic functional programming and getting this working without a Hello World example.

You can download my code here.

Python

I shamelessly stole an idea from my roommate here and decided to make a version of Flappy Bird controlled by light.

I started this at about 9:30 PM on Sunday night (always the best time to start anything, when you have to be up at a reasonable hour on Monday morning) and finished by 1:00 AM. I’m actually pretty proud of that programming speed run. I know Python well, but I haven’t really used Pygame much before, which is what I used to make my game. There was a lot of Googling beginner tutorials here. Luckily, Pygame makes it really easy to get a simple game up and running with the use of Sprites. I used sprites to represent my birdy and all of my obstacles, and with groups of Sprites, Pygame can easily automate moving, drawing, collision detection, and removing off-screen obstacles.

The controls are simpler: brighter light is a higher position for the birdy, and low intensity light is a low birdy position. There wasn’t anything particularly challenging about this, since my adventure in Racket helped me understand the Python serial code. The rest was trying out Pygame things until it worked. The program does seem to run pretty slow (you can see the screen tearing in the video below, and that it starts out really fast but then slows down), but I don’t know why. Can I just go ahead and blame the serial port reading since that’s the part I didn’t write?

Since Neil also wanted user interaction on the computer, I made it possible to click a button to restart the game when your birdy inevitably hits a wall and dies.