For my Senior thesis project I'm working with the Aizenberg lab at Harvard to sense Volatile Organic Compounds indicative of lung cancer in human breath with chemiresistive sensors. Research has shown that you can distinguish between someone with lung cancer and a healthy control based on the signature of VOCs in one's breath. This has been done largely via Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry which is expensive and inaccessible equipment.

The goal of the project is to detect VOCs indicative of lung cancer with chemiresistive sensors to see if lung cancer can be diagnosed easily and inexpensively. The project is chemistry-focused... we're doing testing on arrays of sensors with various VOCs to see if we can achieve a binary classification with 80% accuracy. We've set up a testing rig in the lab and are testing with single gasses/refining our sensor selection. We're soon to move on to mixtures of gasses. This is a difficult problem for a number of reasons. The chemiresistive sensors are not specific--they're sensitive to multiple VOCs. We will have to employ some complex data processing to tackle this. Also, the concentration of the VOCs in the breath is less than the sensors are able to register. This will require preprocessing/selective concentration of the target VOCs which is very difficult. We're hoping to address this with adsorption and thermal desorption or pressure-based concentration.

For my HTMAA project I want to work on device-ifying this technology. I want to start by very simply making an alcohol breathalyzer with an MQ3 sensor. I'm also considering making a breathalyzer with a Hydrogen Sulfide sensor that could detect if you have garlic breath. Ultimately I want to use what I learn in this class and apply it to my thesis, allowing me to create a hand-held breathalyzer-like device that could theoretically be used for lung cancer diagnosis. This is substantially different than the focus of my design project from the lab. This is also certainly preemptive given that we're not sure if we can even detect lung cancer with the chemiresistive sensors, but I think it would be a great project. I would become familiar with system integration, miniaturization, and Embedded System Development. It would also allow me to test with pre-processing human breath to remove noise/moisture.

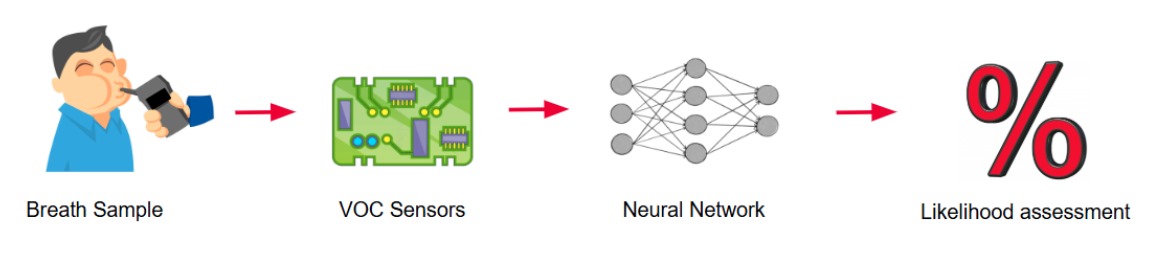

For my final project, I decided to build a breathalyzer. This idea is adjacent to my thesis project. I'm working on my thesis with the Aizenberg lab at Harvard, trying to create a device capable of diagnosing diseases in human breath samples. The device would contain an array of chemiresistive sensors. Mixtures of gasses (or actual breath samples) would be passed over the sensors, and time series data from the sensors would be analyzed by a neural network to determine which gasses are present and whether the breath sample is indicative of a certain disease.

Diagram showing the basic concept of the thesis project.

I started by purchasing a breathalyzer and dissecting it to understand how it works and how its components are laid out.

Dissected breathalyzer components.

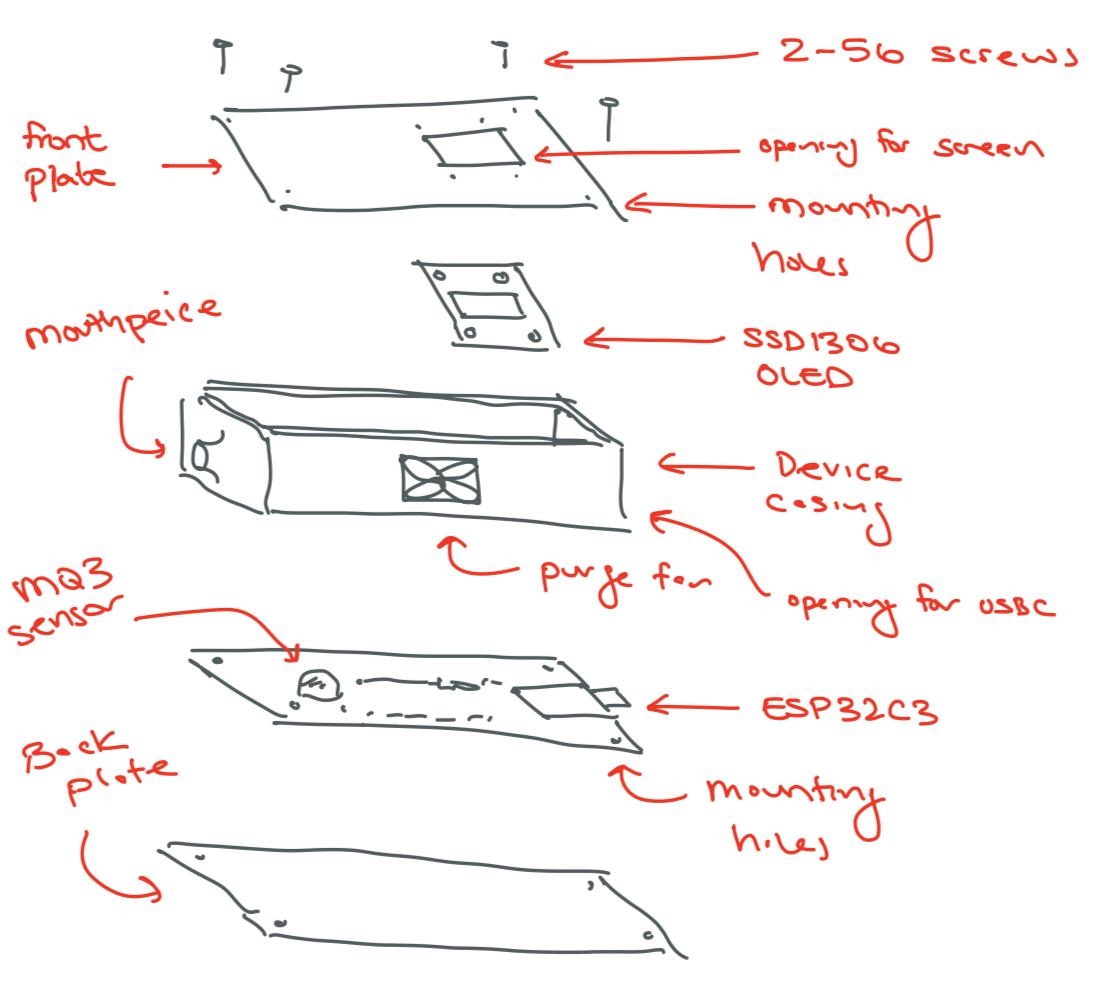

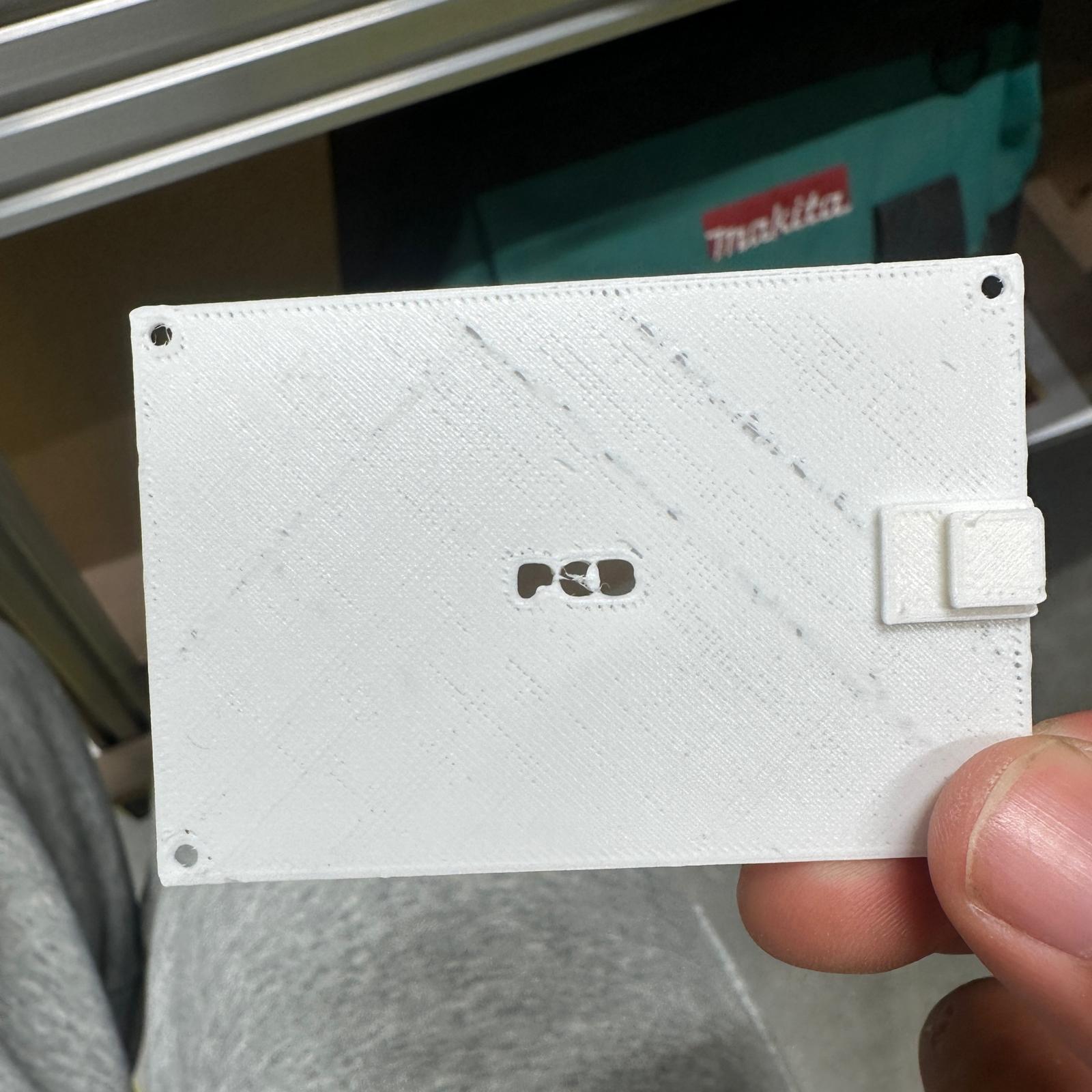

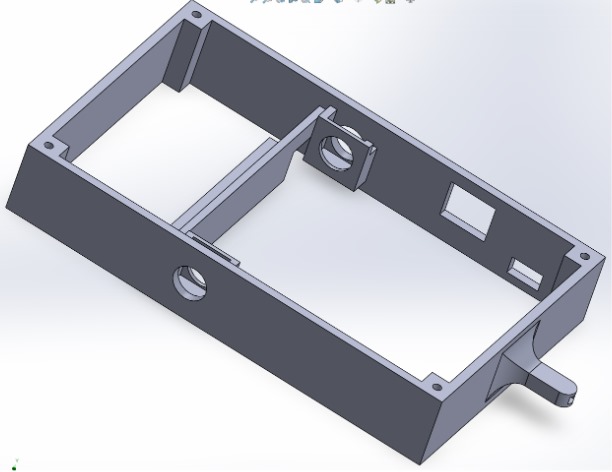

With the extruded view from earlier on this page in mind, I created a second iteration of the device housing. This version included mounting holes, access holes, and slots for specific components.

Device housing with mounting holes and slots.

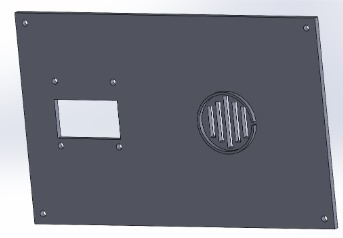

Front plate design for the device.

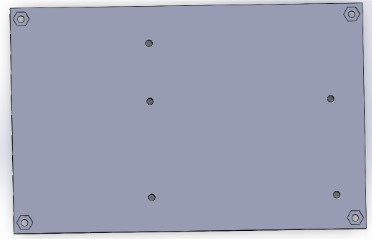

Back plate design for the device.

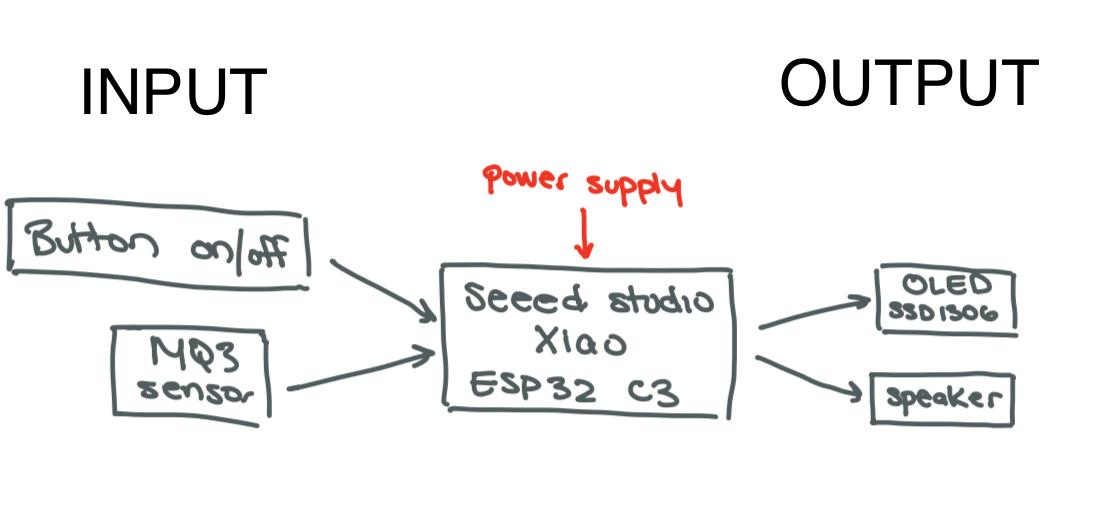

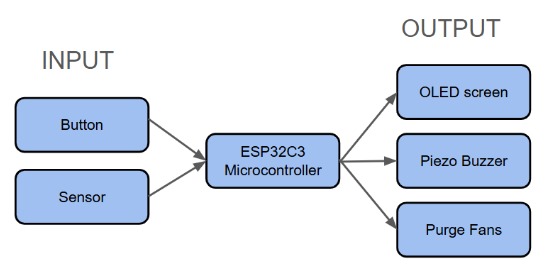

I then began conceptualizing how the circuit would work based on the input and output devices.

Conceptualized circuit for the device.

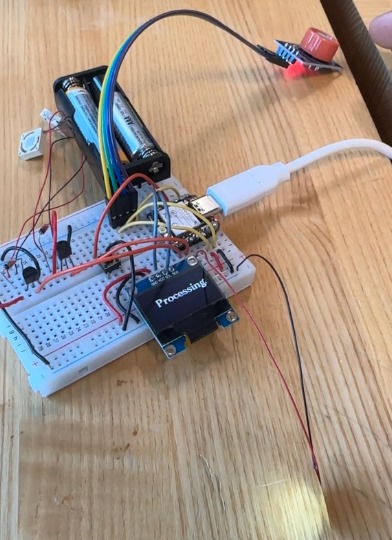

I started by breadboarding each component individually and then integrated all components onto a single breadboard to test the planned circuit and begin working on the code.

Breadboard setup with all components integrated.

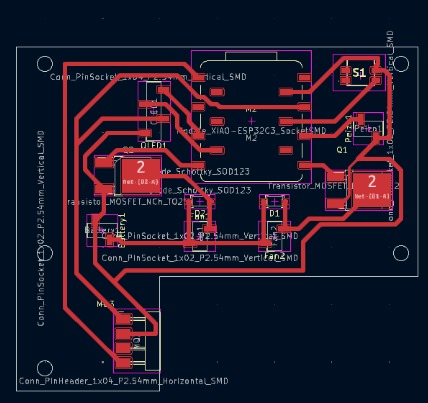

From there, I moved on to designing the circuit in KiCad.

Circuit design in KiCad.

I then milled the PCB from a copper plate using the Roland SRM-20 milling machine.

Milled PCB.

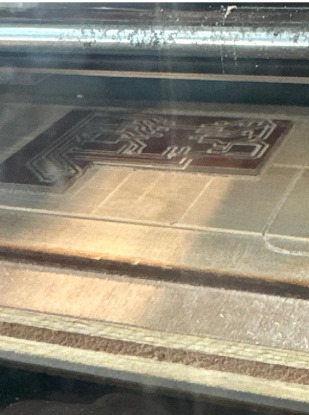

After that, I reflow soldered the components onto the PCB and passed it through the reflow oven.

Reflow soldered PCB.

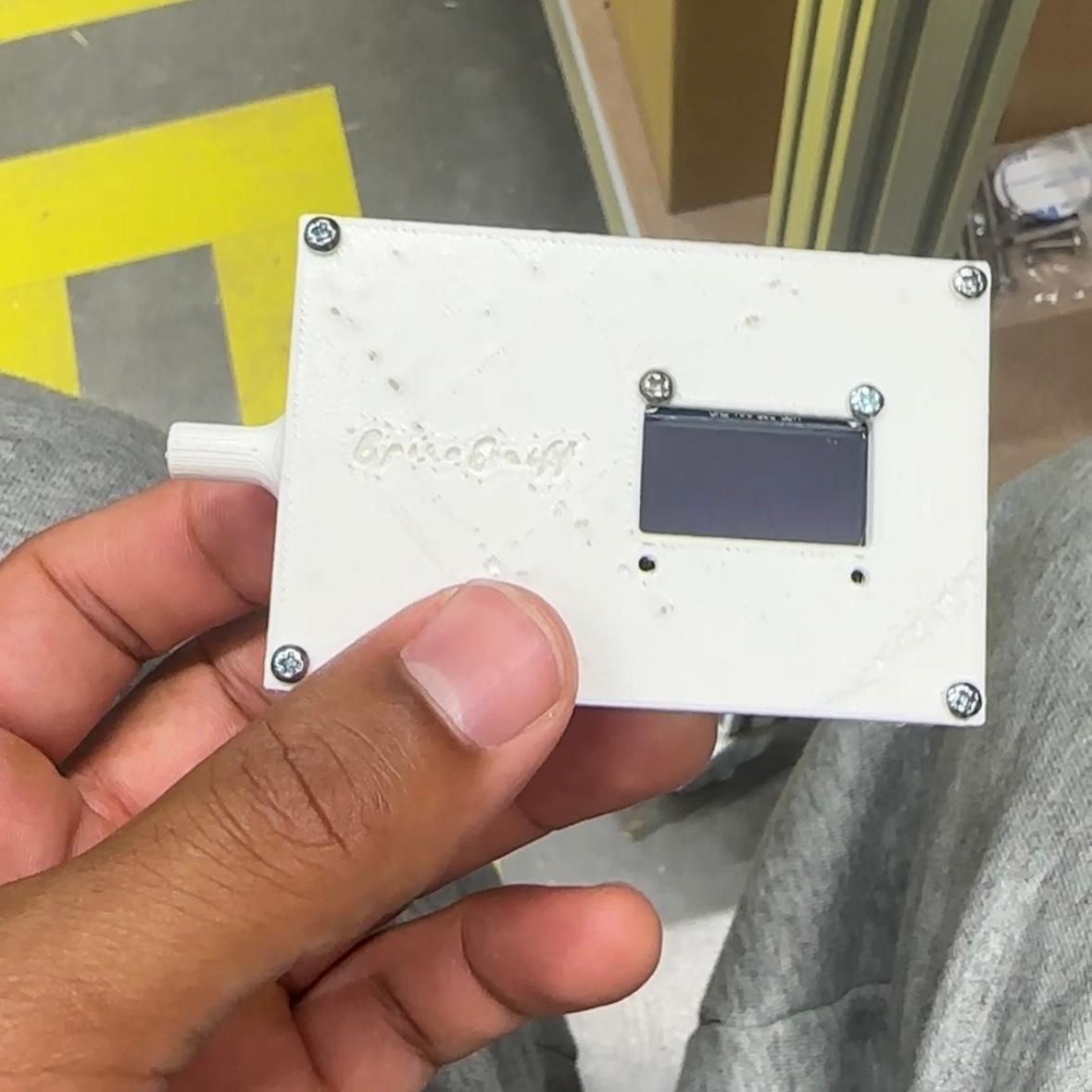

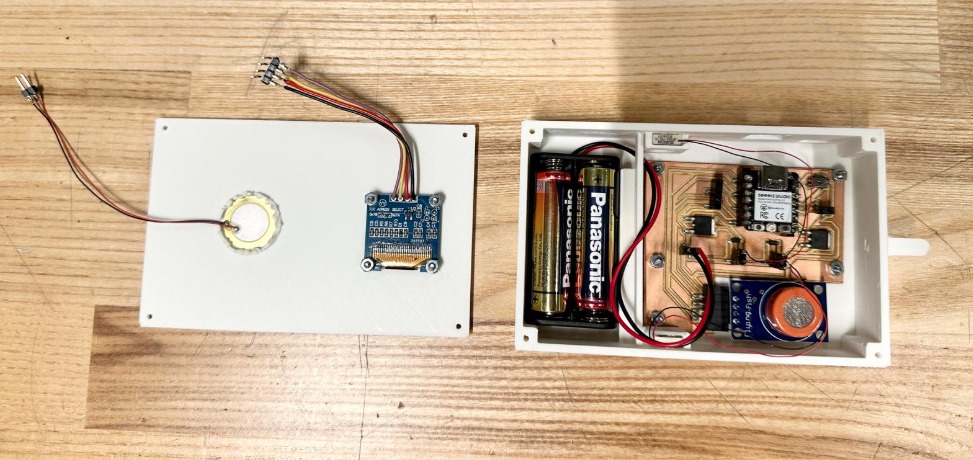

Once the PCB was ready, I mounted all the components and plugged them into their respective headers. Below is an image of the fully integrated device.

Fully integrated device with components visible.

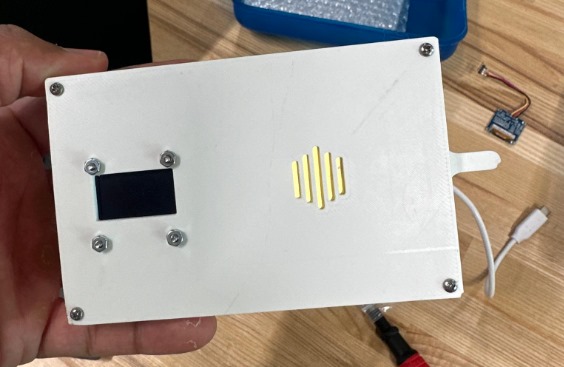

Completed device with the front plate added.

During this process, I had to do some debugging to refine the code. Below is the complete code I wrote in the Arduino IDE to control the device:

You can download the complete code here.

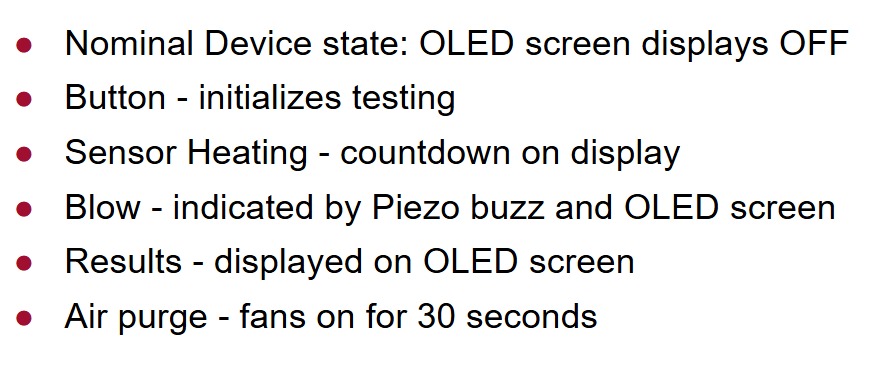

The code worked well, and the image below explains its functionality.

Diagram explaining the functionality of the device code.

The device worked well overall, though I encountered some challenges with sensor drift. To calibrate the device, I sat down with six beers, periodically blowing into it to create a function that converts MQ3 readings to BAC values.

Here is the final video of the project:

This project was a long and difficult process, but it was incredibly rewarding. It gave me valuable hands-on experience with system integration, circuit design, and debugging. I'm confident that the skills I developed here will help me progress on my thesis and future endeavors.