Week 10: MoldingCasting

Nodes, Sukkahs, and Wachsmann

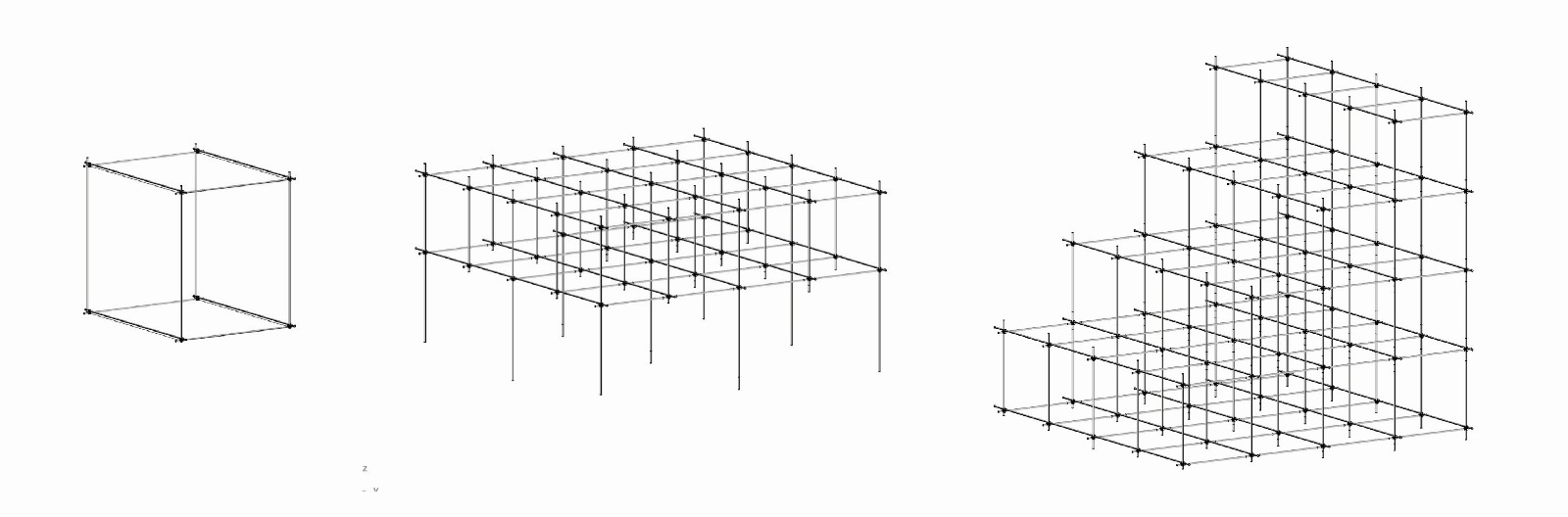

I wanted to make a tillable manifold cast to make a 3D structure with repeating pattern.

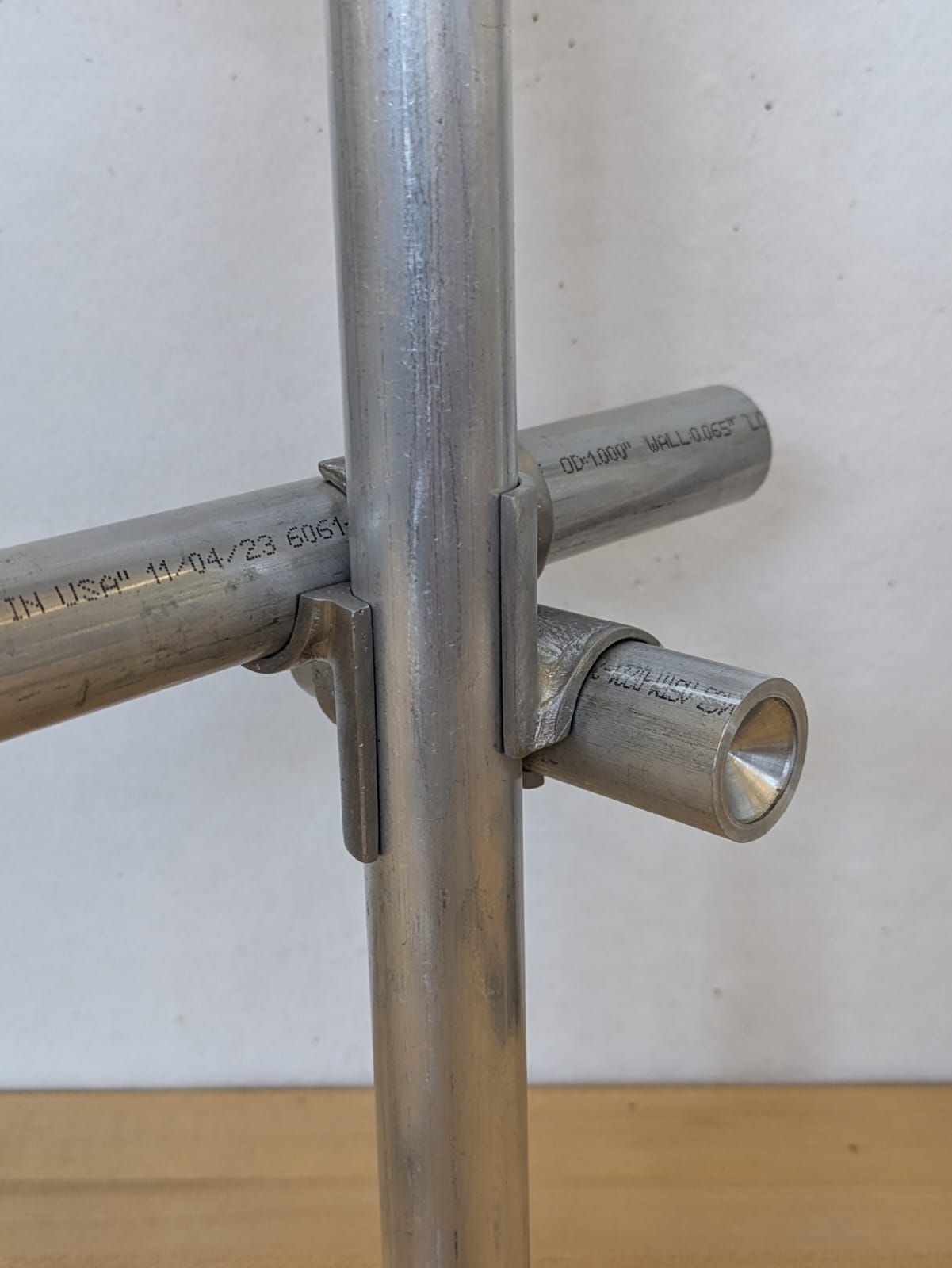

The idea for this week’s project actually began with my brother, who wanted to build a sukkah on his balcony. Most prefab kits rely on heavy metal pipes and extrusions—materials that feel both resource-intensive and strangely detached from the holiday’s emphasis on nature and impermanence. I wanted to design something more graceful—an adaptable system centered around a structural node that could connect natural materials such as bamboo or wood. To explore the geometry, I decided to cast a small three-dimensional joint in metal.

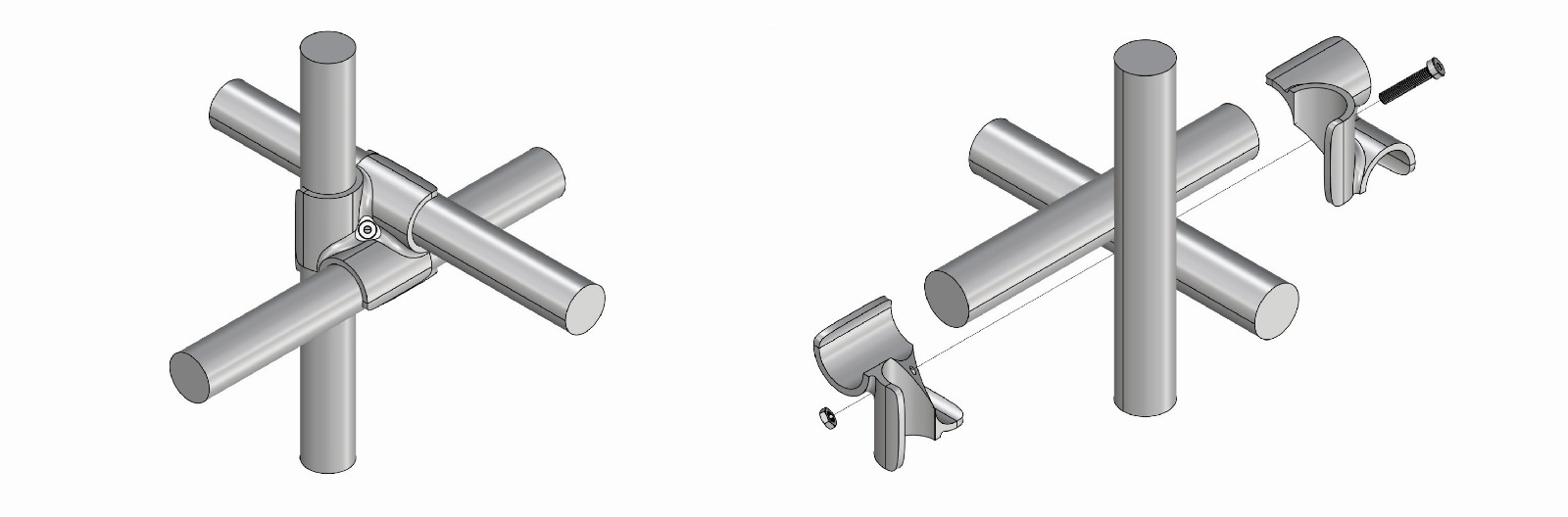

I’ve long admired Konrad Wachsmann, the German-Jewish modernist who revolutionized prefabrication and modular construction. His space-frame systems—especially those developed for the U.S. Air Force—used elegant, repeatable joints that enabled huge spans with minimal material. One particular study model caught my attention: three dowels meeting in space, held by two mirrored half-nodes that clamp together into a seamless, rigid connection. That became my conceptual starting point.

Above: the 3D model for the mold. I plan to cast four to six of these nodes to assemble a small proof-of-concept structure.

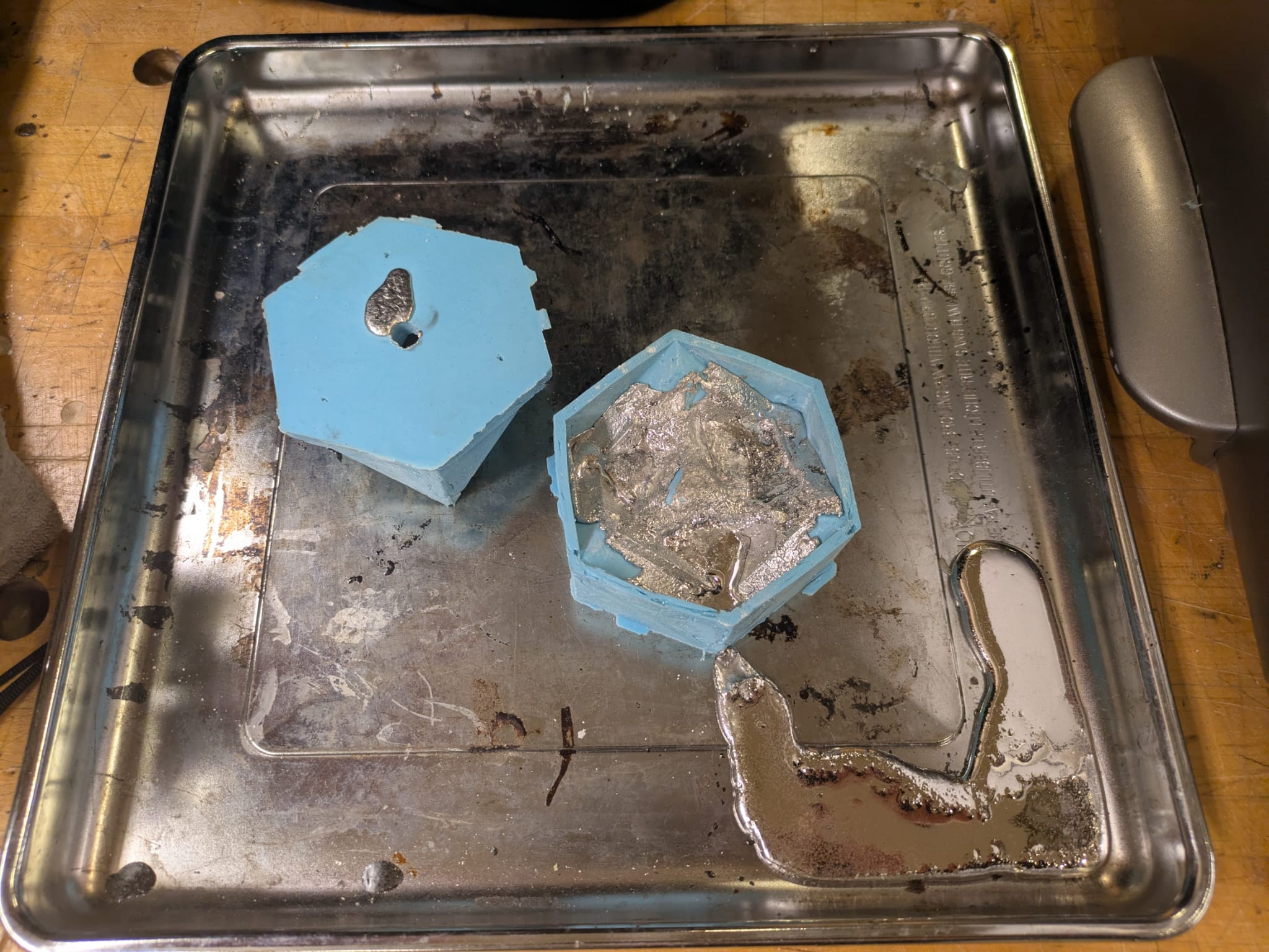

For this first test I used Cerrotru, a low-melting-point bismuth-tin-cadmium alloy that melts around 70–80 °C. It’s easy to handle safely yet solid enough to behave like real metal once cooled. It’s somewhat brittle, but ideal for prototyping. Later iterations could be cast in aluminum or bronze once the geometry and performance are refined.

Our TA, Gert, showed a useful technique: pour molten Cerrotru directly into a silicone mold, but dust the mold with baby powder first so the metal flows smoothly and doesn’t trap air.

What I appreciate about casting is how it inverts your normal design logic. To cast metal, you first need a silicone mold—which itself comes from a 3D-printed positive. The process becomes recursive: print → cast → cast again → pour. It took a moment to internalize this reversal.

Above: the 3D model of the mold. The red line indicates where the two halves meet. I designed the parting line to align with the edges of the geometry so the seam becomes an intentional feature rather than an arbitrary cut.

Diagram showing silicone being poured into the 3D-printed halves.

Diagram showing molten metal poured into the cured silicone mold.

Next steps: finalize vent and sprue placement, run a test pour with Cerrotru, and evaluate whether the node can hold three dowels in compression without crumbling.

Casting Process

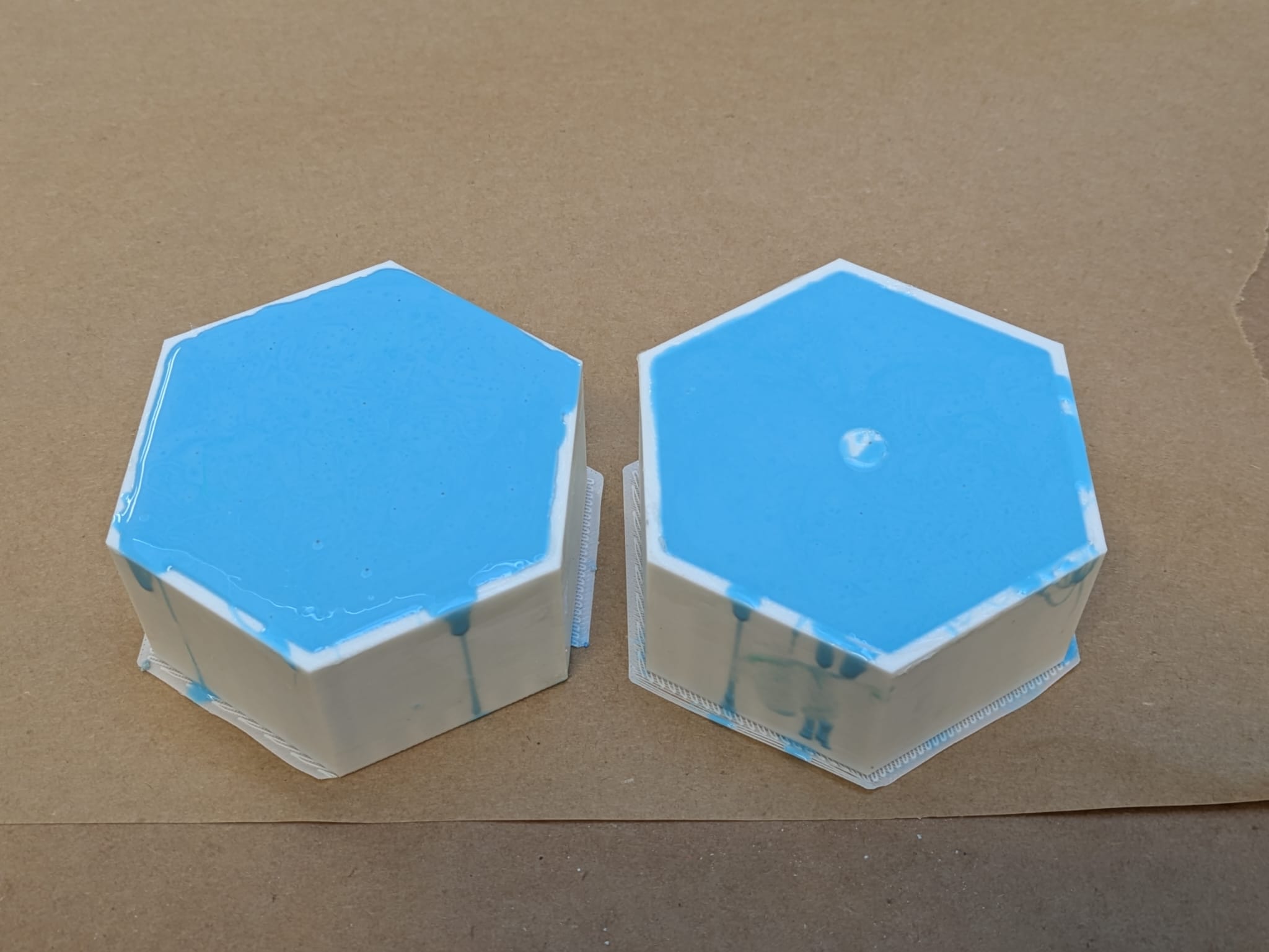

First, I 3D-printed the mold halves in PLA.

Applied a thin coat of Vaseline as mold release.

Mixed the two-part silicone thoroughly.

Poured the silicone and let it cure for over 24 hours.

The silicone released successfully! However, the surface finish was poor— likely because I used too much Vaseline.

The first metal pour failed for two reasons: a small tear in the silicone allowed molten Cerrotru to leak out, and the buoyancy of the liquid lifted the top half of the mold.

Gert suggested clamping a scrap piece of plywood over the top and casting through it—this worked perfectly.

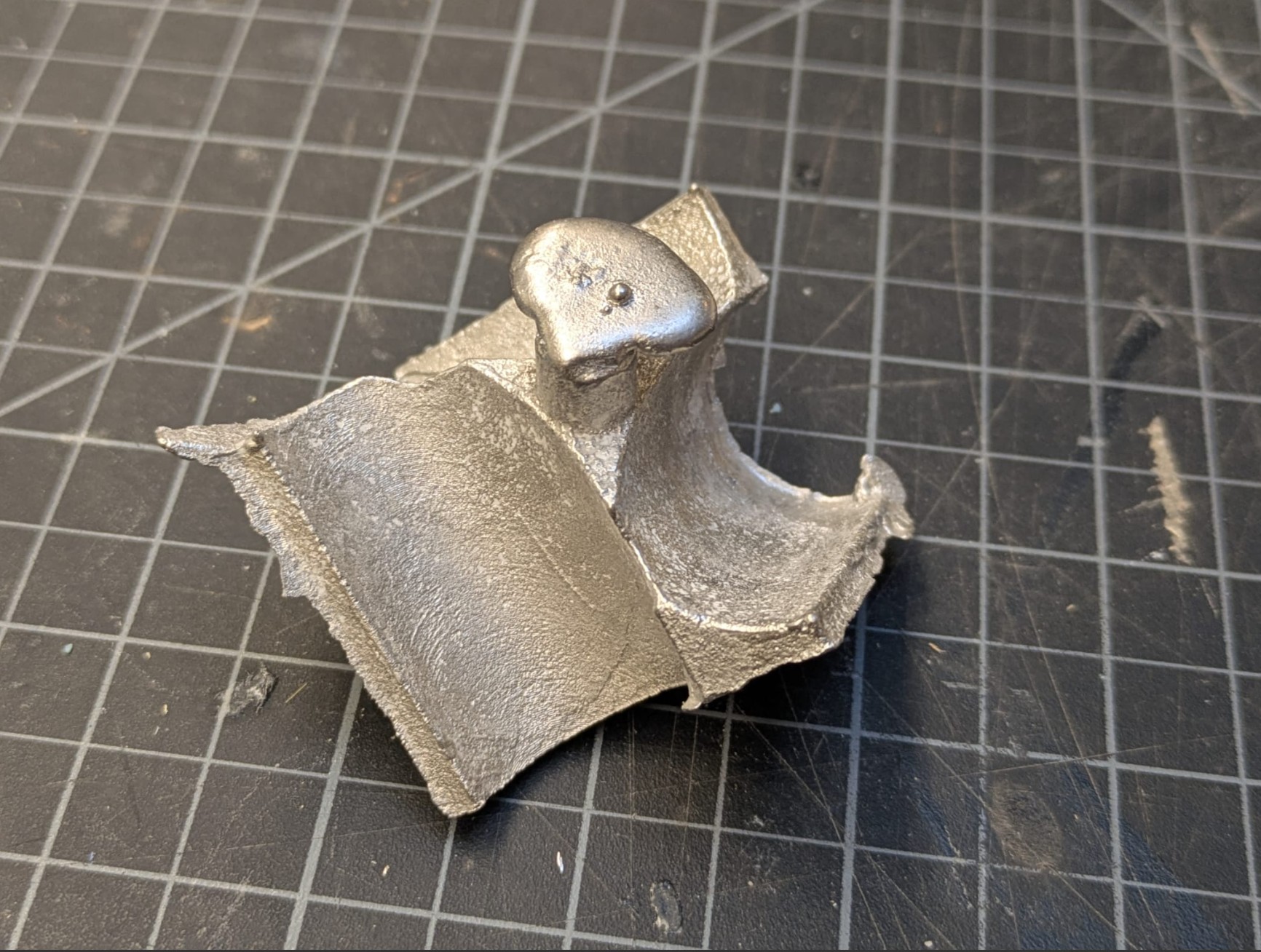

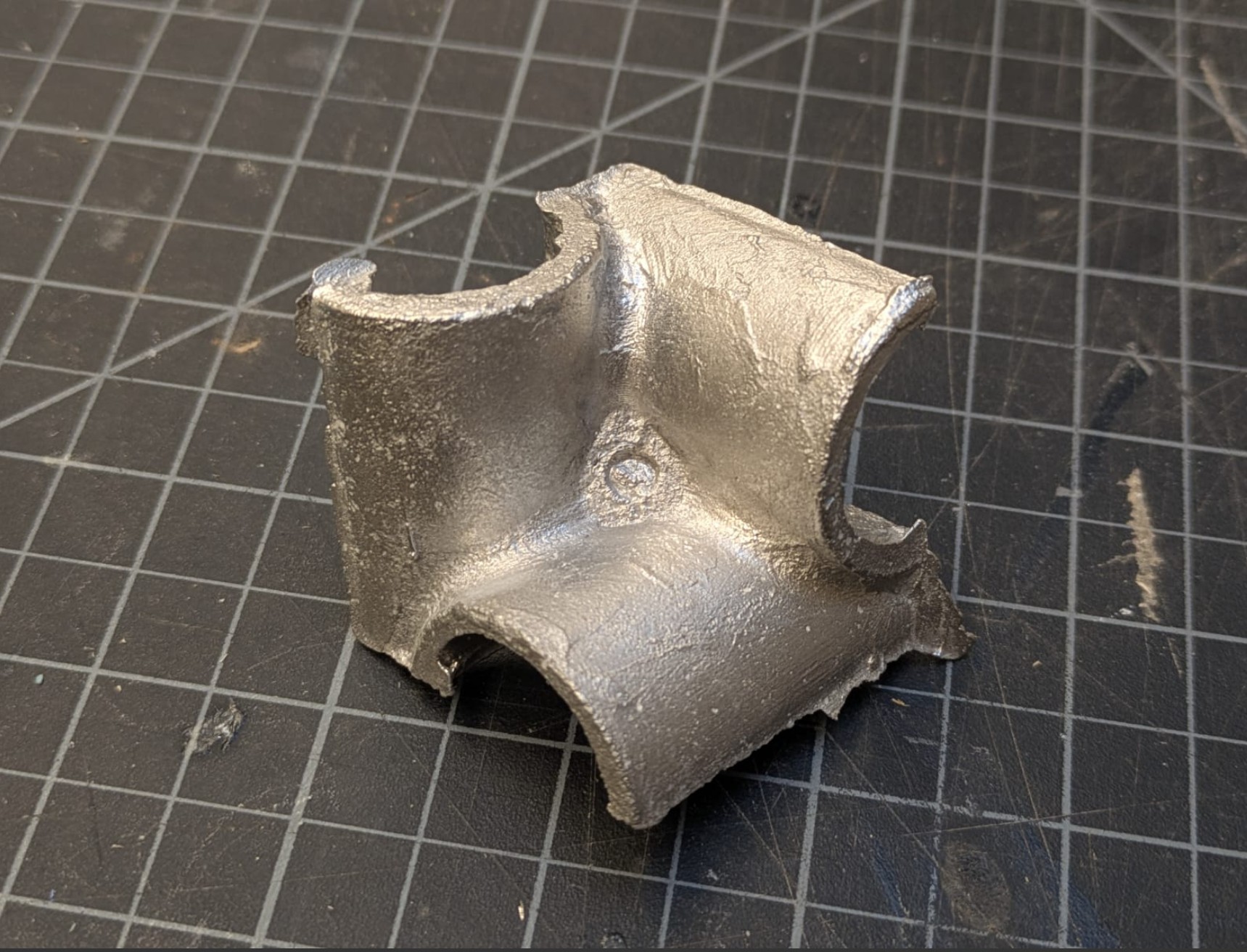

The first successful cast! The surface is still rough, but it can be improved through post-processing.

I used a metal saw to open up the pour hole on the Cerrotru casting.

Close-up of the opposite side showing surface detail.

To finish, I filed the rough edges, sanded with 300-grit paper (both flat and wrapped around a dowel), and used a hand beveler for clean edges. Shout-out to Varun for the tip!

Finished piece, top side.

Finished piece, bottom side.

Takeaways / Reflections

- 3D printing tolerances and surface finishes vary—small calibration errors compound quickly when used for molds.

- Even low-temperature alloys require careful thermal management; pre-heating molds slightly helps reduce cold seams.

- Designing the parting line intentionally improves both appearance and assembly fit.

- This exercise reinforced how material thinking—anticipating flow, cooling, and shrinkage—translates directly into design precision.

Shout-outs

- Huge thanks to Gert for being an incredibly generous TA this week. He worked way over time to meet with every student and show them how to cast the various materials.