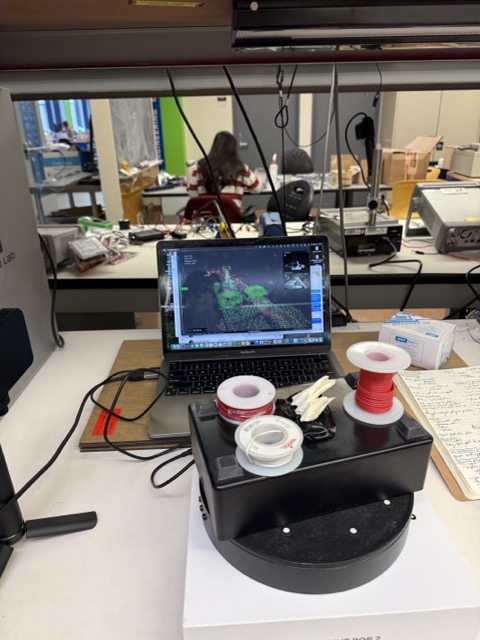

[group work looks like this!]

The teeth are removable, so my first objective-- before the two-step molding and casting process-- was to produce a 3D model of one of them.

The teeth are removable, so my first objective-- before the two-step molding and casting process-- was to produce a 3D model of one of them.

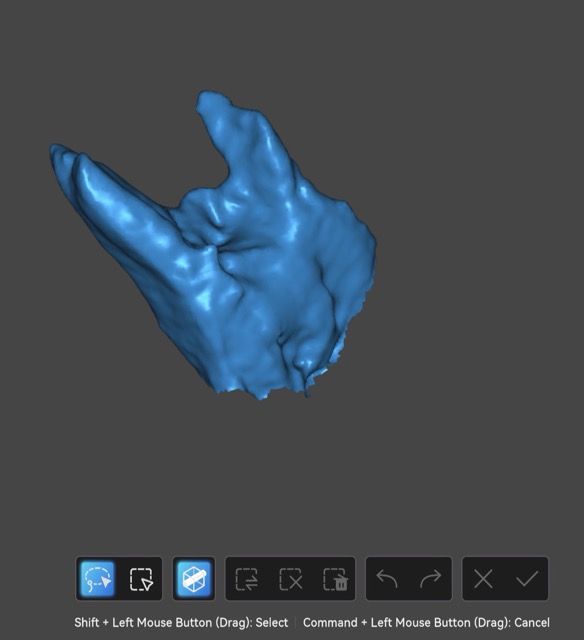

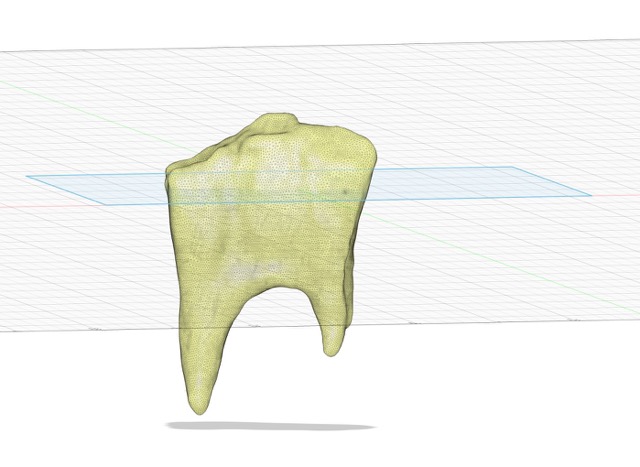

The scanning software still struggled to read the object, resulting in a scan that had two separate representations of the tooth features separated by a trail of noise:

The scanning software still struggled to read the object, resulting in a scan that had two separate representations of the tooth features separated by a trail of noise:

I fixed this by choosing the scene with the better representation of the tooth and deleting everything else using the mesh tools in the Creality app :)

I fixed this by choosing the scene with the better representation of the tooth and deleting everything else using the mesh tools in the Creality app :)

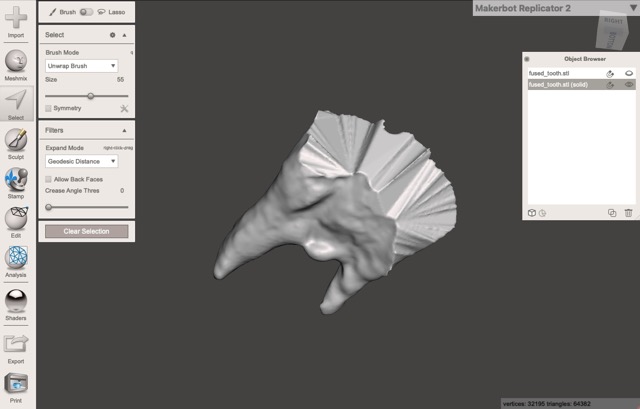

Next, I brought this into meshmixer to close the missing top of the tooth and revise the quality of the model. I initially tried to do this in blender but found it extremely confusing to use the sculpt tools and wasn't having any luck closing the mesh with automatic caluclations, so I gave up and downloaded (yet another) application for the job.

Next, I brought this into meshmixer to close the missing top of the tooth and revise the quality of the model. I initially tried to do this in blender but found it extremely confusing to use the sculpt tools and wasn't having any luck closing the mesh with automatic caluclations, so I gave up and downloaded (yet another) application for the job.

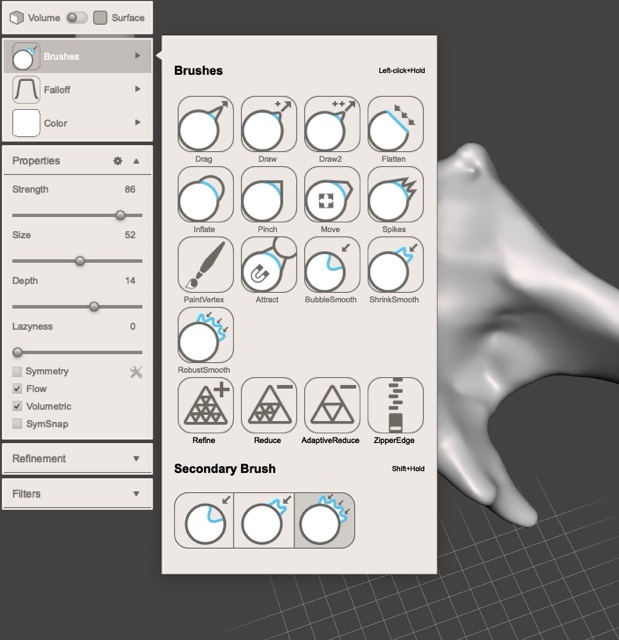

I first closed the mesh as above, using an automatic function for this purpose. Then I used the "draw" and "bubble smooth" brushes below to sculpt the geometry into a more natural and accurate representation of the tooth.

I first closed the mesh as above, using an automatic function for this purpose. Then I used the "draw" and "bubble smooth" brushes below to sculpt the geometry into a more natural and accurate representation of the tooth.

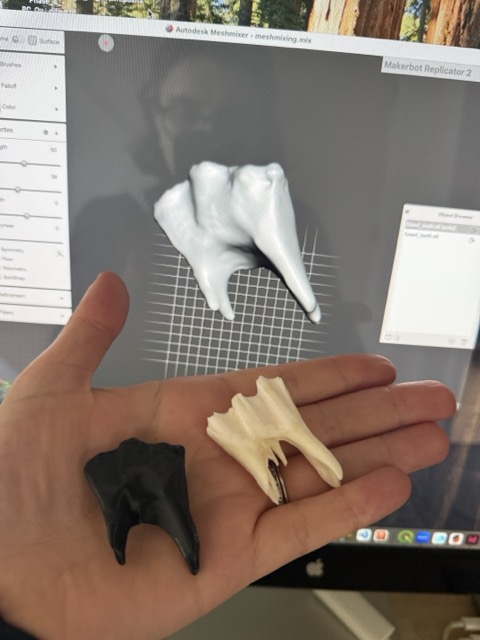

I actually 3D printed the tooth alone before continuing, which was useful to test its fit in the jaw.

I actually 3D printed the tooth alone before continuing, which was useful to test its fit in the jaw.

After printing and trying to replace the real tooth with my PLA one, I found that my scanned mesh was a bit too big in certain places for the tooth to fit all the way into the jaw:

After printing and trying to replace the real tooth with my PLA one, I found that my scanned mesh was a bit too big in certain places for the tooth to fit all the way into the jaw:

So I went back to meshmixer and revised it before continuing.

So I went back to meshmixer and revised it before continuing.

With my revised mesh of the actual tooth, I was ready to start making my positive mold. To save time, I didn't print it again, knowing that minor issues could be fixed with a file later on.

With my revised mesh of the actual tooth, I was ready to start making my positive mold. To save time, I didn't print it again, knowing that minor issues could be fixed with a file later on.

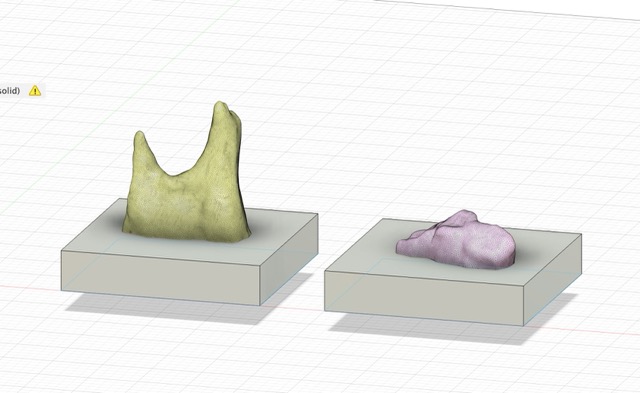

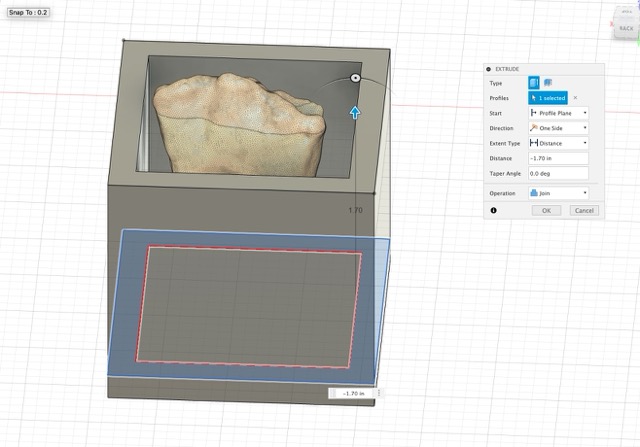

Then, I built boxes around the two components of the tooth. For clarity, here they are separated, but I actually did this whole process with the pieces still together, to ensure that they would register correctly when assembled. I did this by turning on and off the visibility of different components to work on one or both at a time.

Then, I built boxes around the two components of the tooth. For clarity, here they are separated, but I actually did this whole process with the pieces still together, to ensure that they would register correctly when assembled. I did this by turning on and off the visibility of different components to work on one or both at a time.

Even with the pieces in place, I found this confusing spatially and at some point started building one of my boxes inside out by accident:

Even with the pieces in place, I found this confusing spatially and at some point started building one of my boxes inside out by accident:

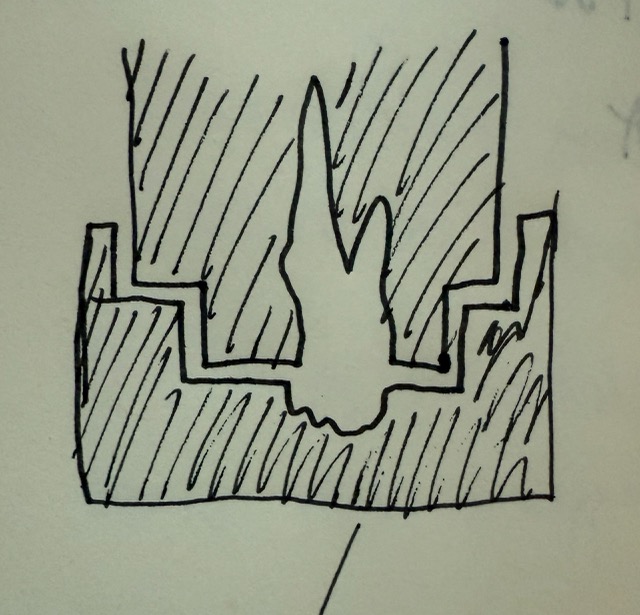

It was actually a basic hand-sketch of the pieces that helped me keep this straight in the end.

It was actually a basic hand-sketch of the pieces that helped me keep this straight in the end.

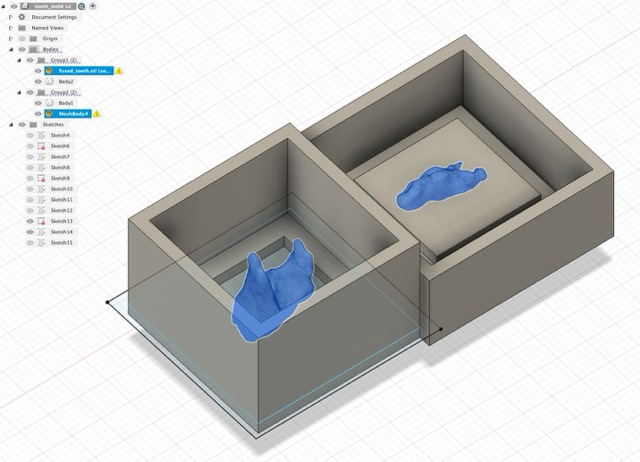

Eventually, I came up with a model of the full system to be printed and cast in silicone:

Eventually, I came up with a model of the full system to be printed and cast in silicone:

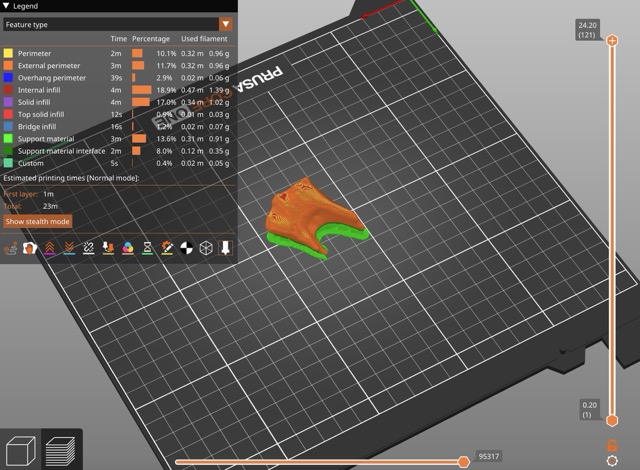

This I sent to Anthony who generously offered to slice and submit it to the 3D printers for me remotely while the EECS lab was closed.

This I sent to Anthony who generously offered to slice and submit it to the 3D printers for me remotely while the EECS lab was closed.

Before starting the casting process, I reviewed SDS materials for our molding media and reviewed some of the group examples. More information on this here!

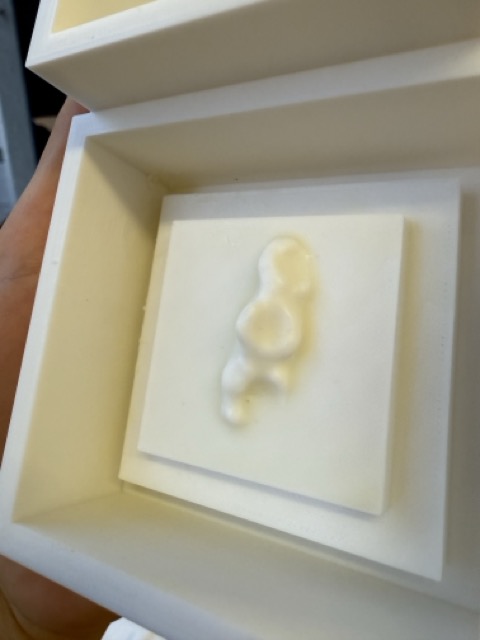

I learned that this was because Jesse and Anthony sliced it at 0.1" rahter than 0.2" (which would be standard). Noting the aspiration to completely eliminate these marks, I still used hot wax and a little paintbrush to smooth out the surface:

I learned that this was because Jesse and Anthony sliced it at 0.1" rahter than 0.2" (which would be standard). Noting the aspiration to completely eliminate these marks, I still used hot wax and a little paintbrush to smooth out the surface:

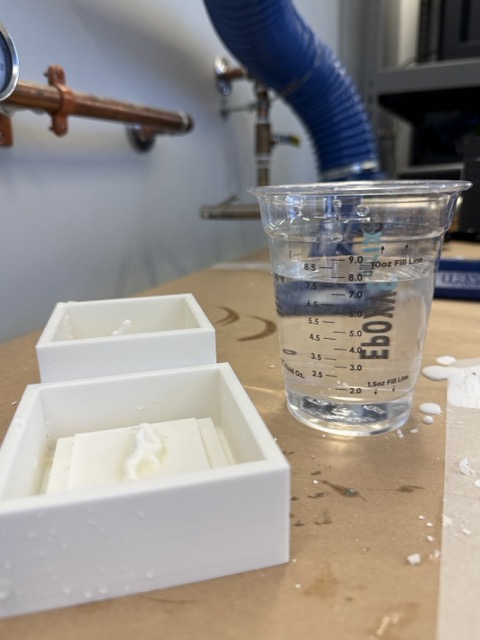

Next, I needed to create the silicone medium for the mold. I filled my negative mold with water and then poured it into a graduated cup in order to calculate the amount of medium needed to fill the mold.

Next, I needed to create the silicone medium for the mold. I filled my negative mold with water and then poured it into a graduated cup in order to calculate the amount of medium needed to fill the mold.

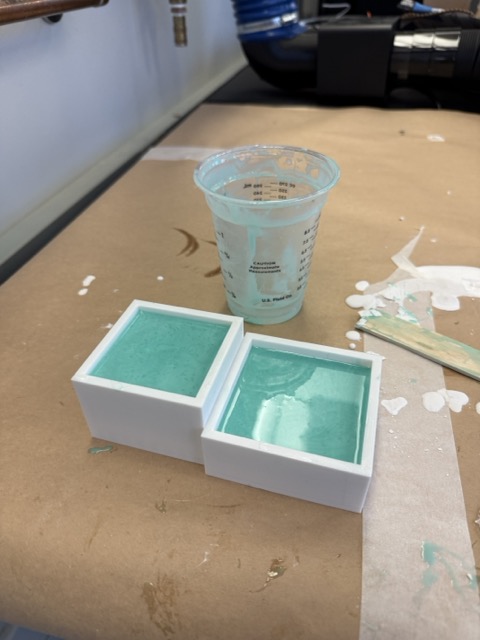

Then, I poured out and dried the cup and the mold with paper towels before mixing the moldstar. It takes a 1:1 ratio of parts A and B. We had open set of jars in the lab, and although I initially calculated that I would need 7.75oz, the combined volume of medium in the jars was just abou 7oz. Since the bottles noted that they were perishable and I was one of the last students to make a mold this week, I decided against opening more moldstar. Waste not, want not!

Then, I poured out and dried the cup and the mold with paper towels before mixing the moldstar. It takes a 1:1 ratio of parts A and B. We had open set of jars in the lab, and although I initially calculated that I would need 7.75oz, the combined volume of medium in the jars was just abou 7oz. Since the bottles noted that they were perishable and I was one of the last students to make a mold this week, I decided against opening more moldstar. Waste not, want not!

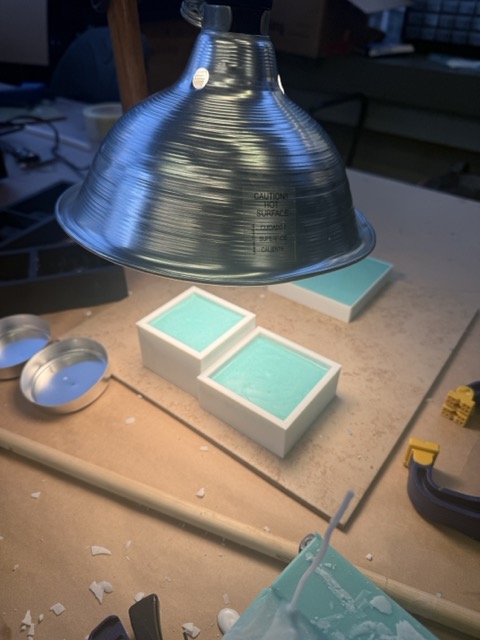

Then, I placed my molds under a lamp to raise their temperature so that they would cure faster.

Then, I placed my molds under a lamp to raise their temperature so that they would cure faster.

When I removed them after about an hour, they registered together well although there were some bubbles they didn't intersect with the surface of the mold luckily.

When I removed them after about an hour, they registered together well although there were some bubbles they didn't intersect with the surface of the mold luckily.

Now it is time to cast!

Now it is time to cast!

When I removed the drystone after about an hour, it seemed set, but the long roots of the teeth snapped a bit below the fill holes I had made, resulting in a slightly shortened shape. I set about fixing and smoothing with a file:

When I removed the drystone after about an hour, it seemed set, but the long roots of the teeth snapped a bit below the fill holes I had made, resulting in a slightly shortened shape. I set about fixing and smoothing with a file:

In the end, comparing the tooth cast to the original tooth revealed a lot of lost detail-- which made me wonder how much more could have been preserved by simply casting a negative mold around the original tooth. I also noticed that because my mold may have been insufficiently held together and my drystone mixture was very liquid, some had seeped out of the gap where the sides of the mold came together, so I did my best to file this down as well.

In the end, comparing the tooth cast to the original tooth revealed a lot of lost detail-- which made me wonder how much more could have been preserved by simply casting a negative mold around the original tooth. I also noticed that because my mold may have been insufficiently held together and my drystone mixture was very liquid, some had seeped out of the gap where the sides of the mold came together, so I did my best to file this down as well.

While the tooth did fit into the jaw, and it looked better than the first 3D printed version, it left something to be desired aesthetically. In case of future bovine cosmetic dentistry needs, I will probably hold my mold more tightly together, let it cure longer, and consider putting the seam between the two sides at a less visible place.

While the tooth did fit into the jaw, and it looked better than the first 3D printed version, it left something to be desired aesthetically. In case of future bovine cosmetic dentistry needs, I will probably hold my mold more tightly together, let it cure longer, and consider putting the seam between the two sides at a less visible place.