Overview

This week was networking and communications week. The assignment was:

"Design, build, and connect wired or wireless node(s) with network or bus addresses and local input &/or output device(s)"

Project Files

- Week 12 Lecture Notes

- Week 12 Recitation Notes

- Week 12 Supplement Notes (from the extra session with Dimitar)

Group Assignment

Our group assignment was:

"Send a message between two projects"

You can find what Ruipeng and I did to complete it below.

Group Assignment

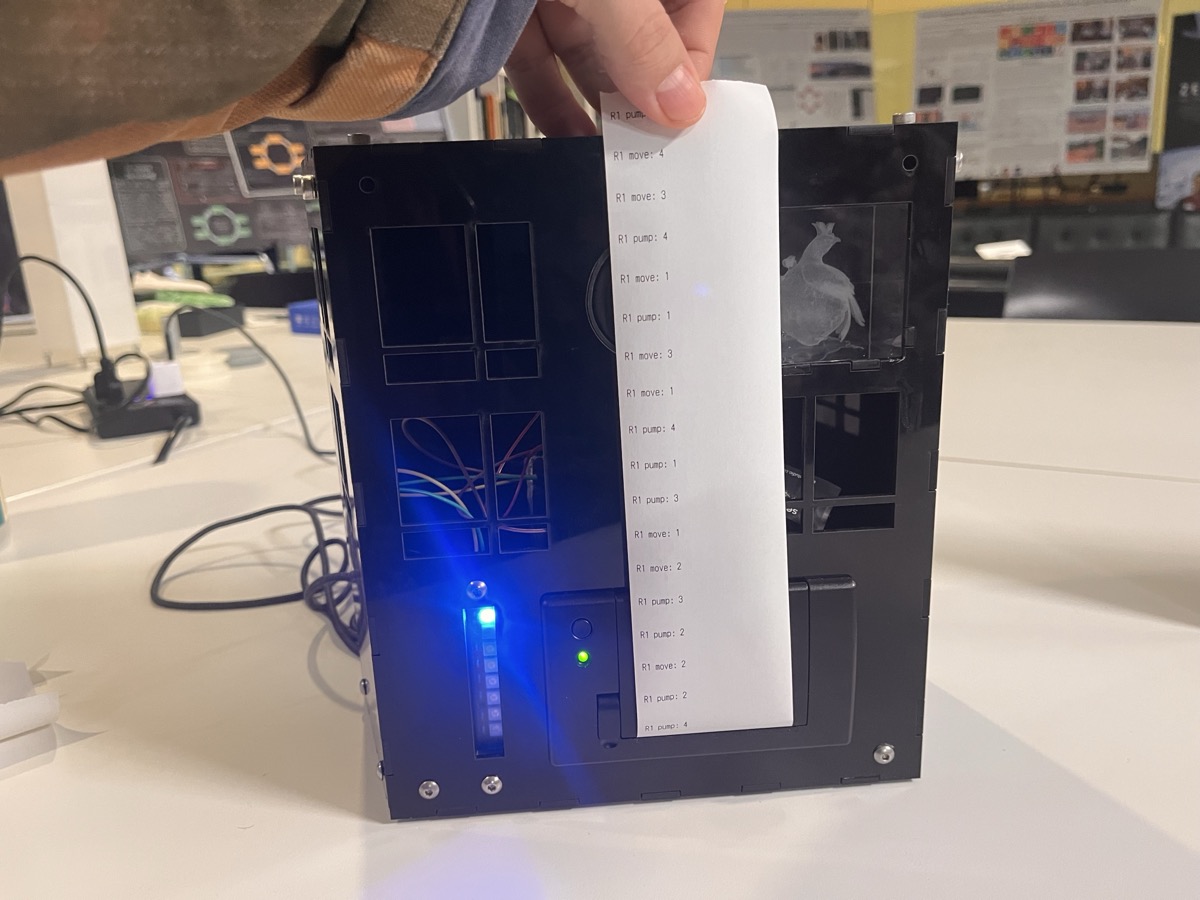

Ruipeng's final project was a Baby Robot , which could move around

through a web interface he'd programmed. We wanted to try to see if we could print out the different control states as he adjusted them on his interface,

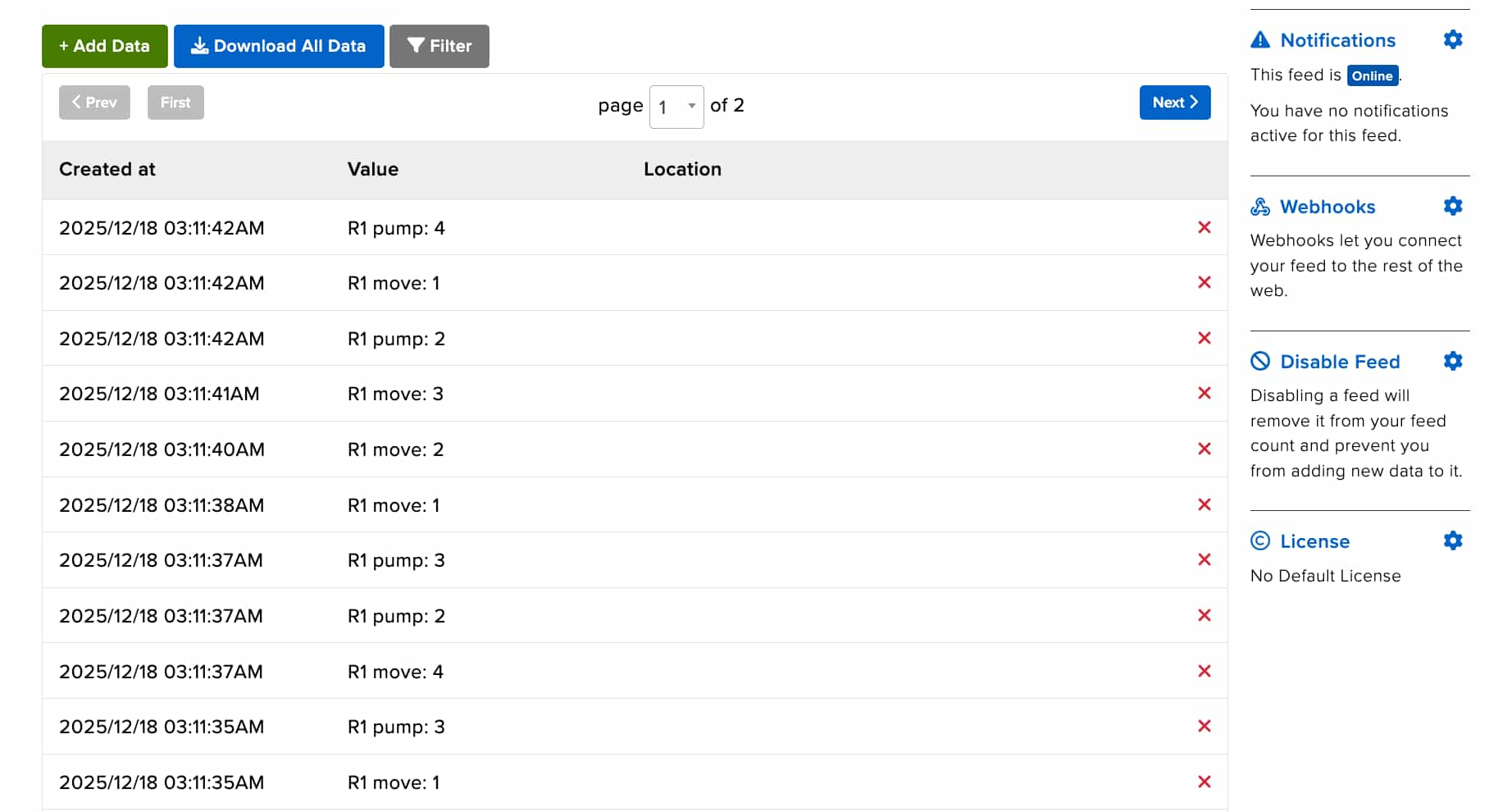

so we added some lines to his code to send any input changes through the same MQTT / Adafruit IO server that I used for my printer.

Lo and behold – it worked!

Check out the video here for more information:

Individual Assignment Details

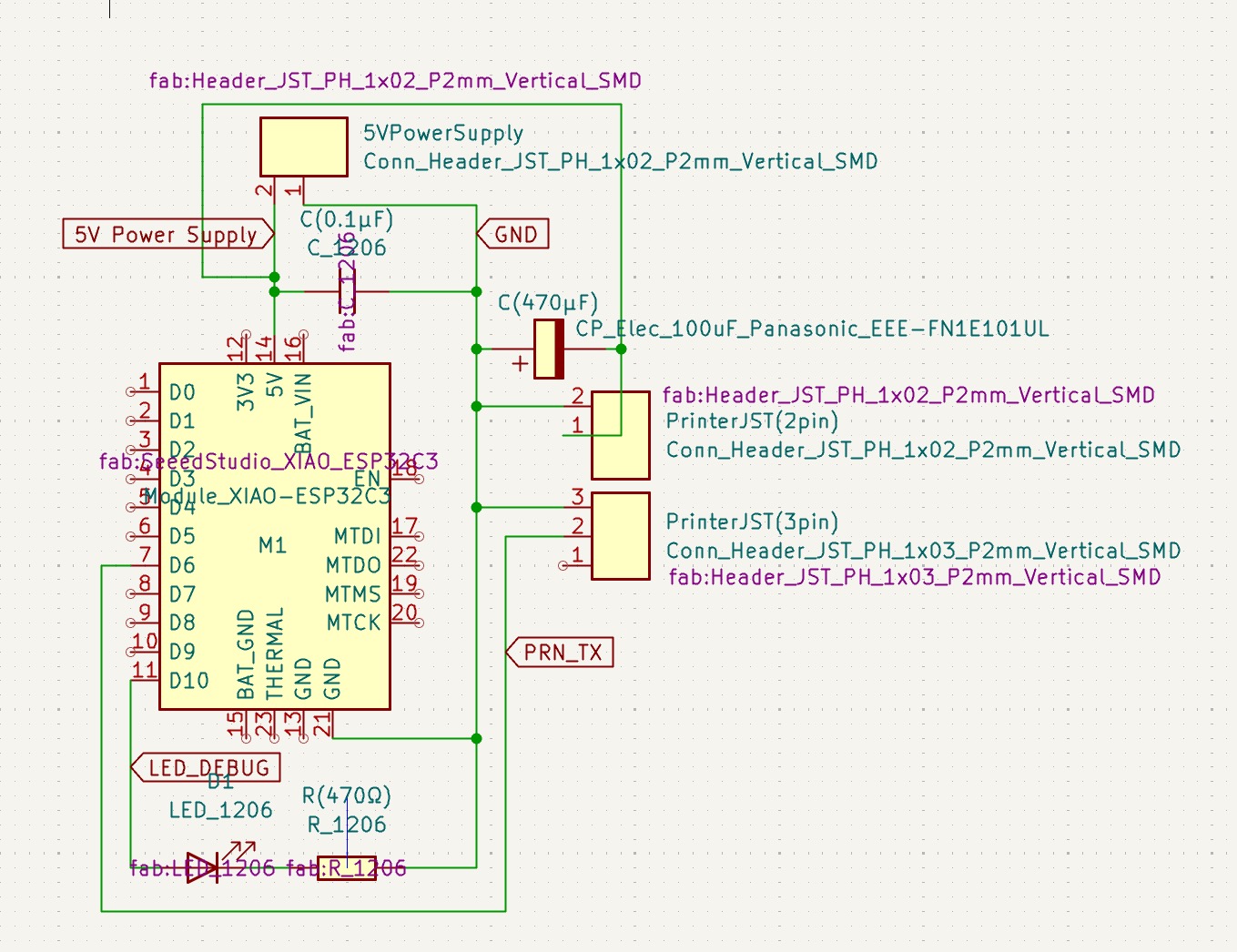

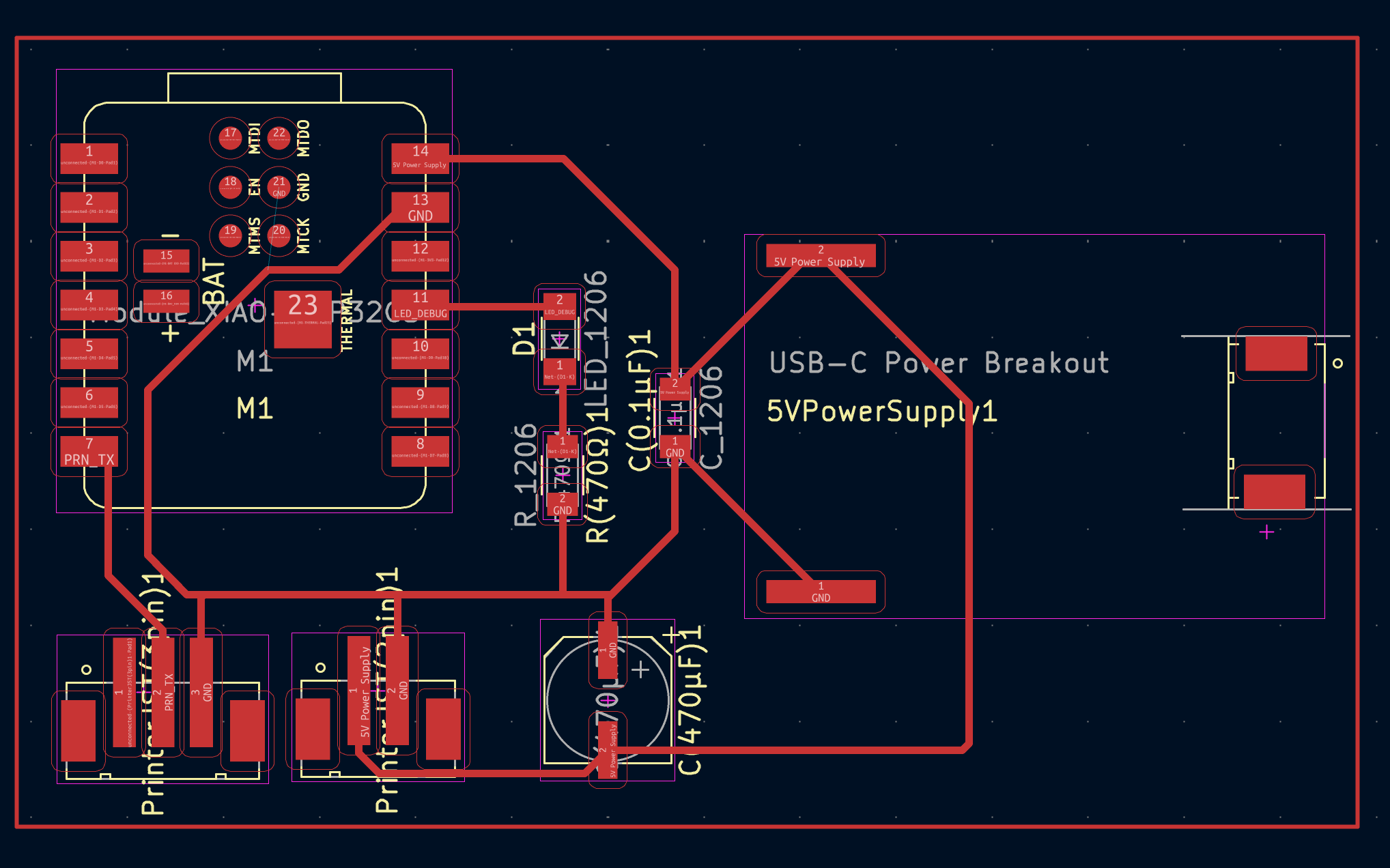

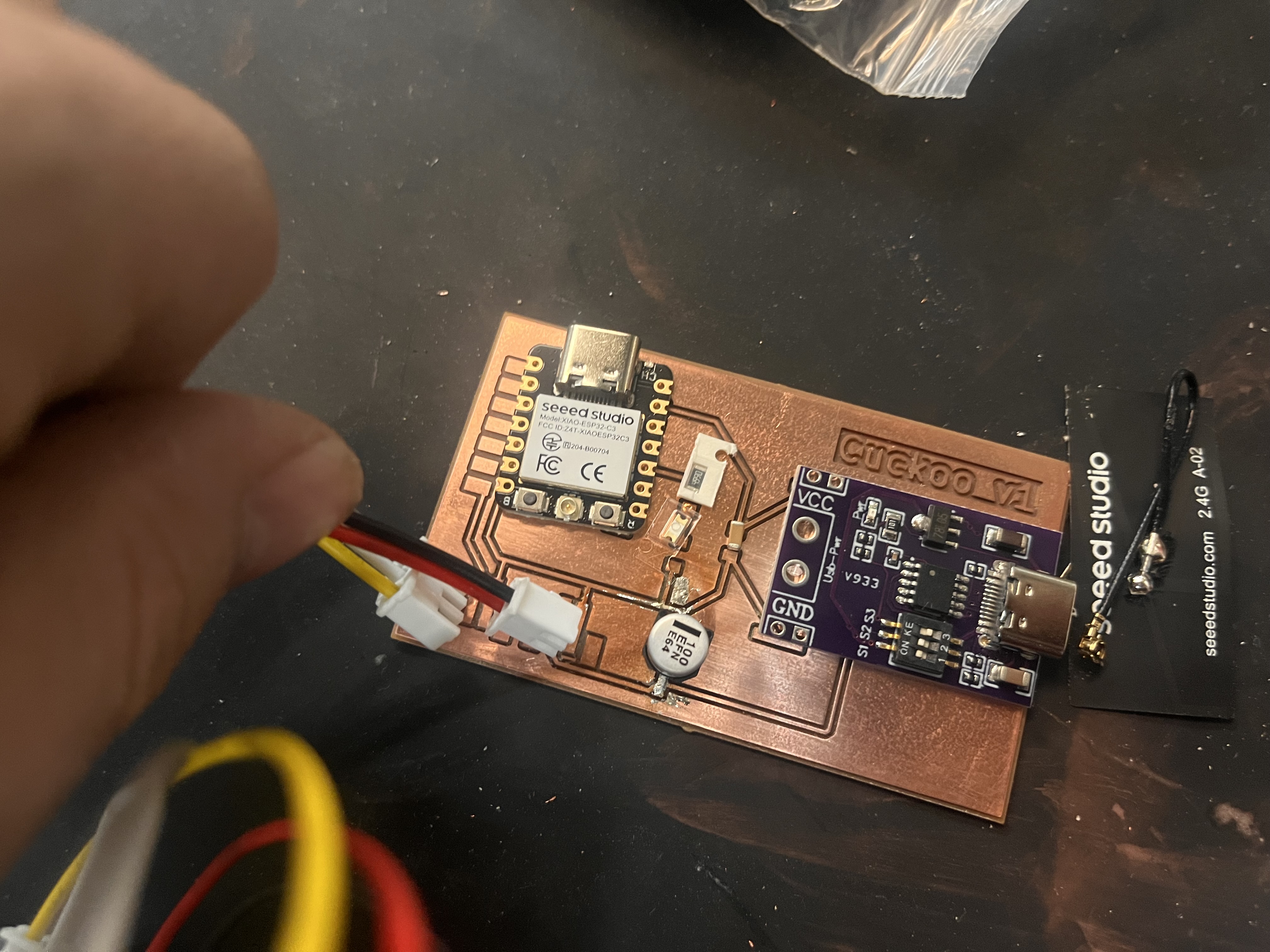

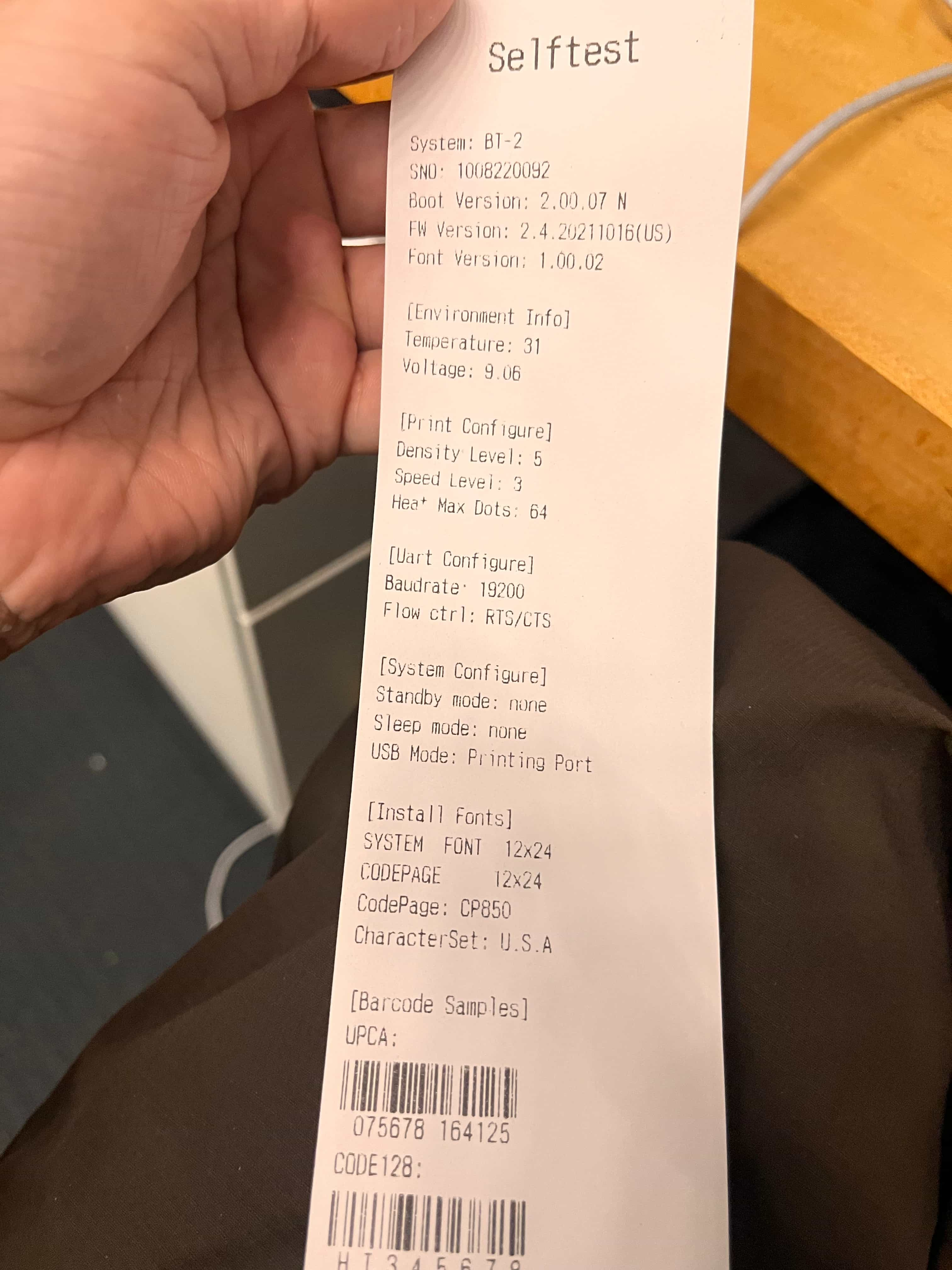

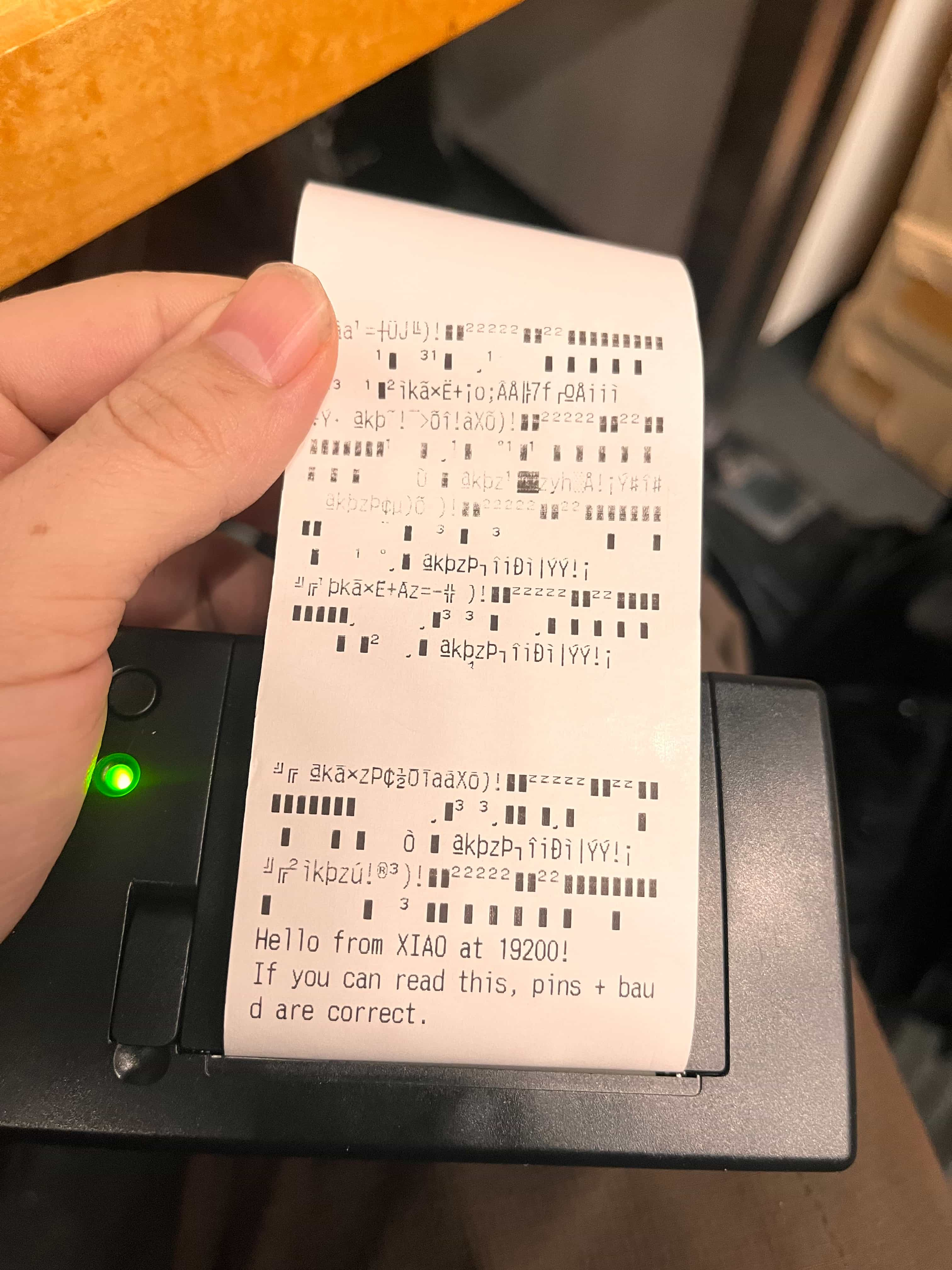

I was pretty dang burned out right off the tail of Machine Week , so I really wanted to take this week a little lighter. I worked on v1 of my final project board, and focused on getting the receipt printer up and running over a WiFi network. The onboard XIAO ESP32C3 connects to WiFi and is synced up with a feed on Adafruit I/O, which sends it text over UART to the printer.

Post–Final Follow–up: How Networking Works

Future Eitan Note: I'm returning to this page after the final to fill out more information about what I learned around networking. I had a two hour learning session with Dimitar, and used Claude (prompt: "I have some shorthand bullet notes that I'd like to turn into longer paragraphs, matching the style from this page) to expand my original notes into these sections below:

The Physical Hardware

The Xiao ESP32-C3 has both a power amplifier and low noise amplifier built in. It sends signals at either 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz frequency to an access point (AP). An access point is different from a router, though most routers have an access point built into them. The Xiao also has modulation and demodulation capabilities—it converts 1s and 0s into electrical signals at those frequencies and vice versa. This is all part of the physical layer (PHY), which is Layer 1 of the networking stack.

Layer 1: Physical Layer (PHY)

The physical layer manages the actual air or physical wire—basically how you "wiggle the thing" to transmit data. There's only one channel (the air), which creates the first major problem: who talks to who, and when? Each device can communicate at various rates. The lowest rate uses 2 symbols, then 4, then 16, then 64, then 256, and so on—all powers of two because of legacy radio architecture. Modern systems use direct sampling so this doesn't matter as much anymore, but the pattern remains. The first two symbols tell you how the rest of the signal will be decoded.

Wi-Fi works by using amplitude modulation (AM) and phase modulation (PM) simultaneously. If you plot the signal on a polar plot, each part of the signal has both an amplitude (the angle) and a phase (the dot position). You create a grid of possible dots, and when you transmit a signal close to one of those dots, the receiver essentially says "oh, you probably meant this one." Having only a certain set of valid values helps with error correction. Forward error correction is one of the black magic aspects of networking (the other being antennas)—you send extra bits in a special way that makes it easier to figure out what you actually meant, similar to how you can understand a misspelled word as long as the rest is spelled correctly.

Layer 2: MAC (Medium Access Control)

The MAC layer manages who talks to who in a room full of wireless signals. It controls who talks when, handles device addresses, breaks information into packets, manages association between devices (agreeing on how to speak and understand each other), and does rate adaptation. The channel might get worse or better over time, so the system needs to adjust the data rate accordingly.

Frequency is how fast the sine wave moves up and down, but it's not exactly what encodes the information—you can also modify amplitude, phase, and frequency. Frequency modulation (FM) means the frequency deviates from a center point. This is particularly useful because amplitude doesn't matter—if you go through a tunnel and the signal gets weaker, FM still works. With AM, that same situation would sound quieter (unless you have radio components designed to compensate). AM means the wiggle goes more or less, while PM (phase modulation) modulates the rate at which the phase progresses through its cycle rather than maintaining a continuous phase.

For Wi-Fi, if two devices talk at the same time, they both have to retry. The system uses CSMA/CA (Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance) to handle this. It figures out when multiple devices want access by listening—if a device hears activity on the air, it doesn't talk. The protocol assumes everyone can hear everyone else. Once someone finishes talking, other devices pick a random number, wait that long, and then transmit. Your access point tells you the range of random numbers you can pick, though the vast majority of routers don't expose this as a setting.

Layer 3: IP Layer

While MAC and PHY let a couple devices in the same room or on the same table talk to each other—essentially devices that are close by and can "hear" each other—the IP layer is responsible for getting data across actual networks. When you have your Xiao talking to an access point, which connects to a router, which talks to different boxes along the way until it reaches the Adafruit server, each step needs to figure out how to route information. Each point along the way has its own MAC and PHY.

IPv4 determines the optimal route to get data to the destination. Within each network space, it finds the best way to route packets. Routes change constantly—some get faster, some get slower, some disappear entirely. It's difficult to maintain symmetry, meaning you want the uplink and downlink to follow the same path. Everything connects to your router in a star topology, and the router connects up in a tree system. But after that there are multiple possible paths, and ideally you want to keep the same path in both directions.

The router talks to a modem, which talks over coax (using different PHY and MAC layers), then over fiber to your ISP like Comcast. Certain VPNs break the traditional layers by using tunneling, where symmetry becomes very important. VPNs still know where traffic came from, so you shouldn't trust them as a free pass to do something illegal—they keep logs of who requested what. Tor was designed differently—it broke everything up across many computers—but still gets stuck at exit nodes, which need a "fall guy" where everything comes together. These are often run by people who don't realize what they're getting into.

Layer 4: Managing the Session

Layer 4 manages the relationship with your destination. This includes TCP and UDP, which run on your Xiao and dump information through the lower layers. UDP takes care of chopping data into packets for you and handles port numbers and addresses. The IP identifies the computer, while the port identifies what program on that computer you're talking to.

TCP does more: it ensures delivery by requiring acknowledgment, ensures everything arrives in order, and keeps track of bandwidth through congestion control using algorithms like Cubic (before that, Reno and Vegas). This is an interesting balancing act. You're sending discrete packets out in order, and they take time to arrive—anywhere from a couple milliseconds to a second. If you sent them one by one and waited for each to return, it would take forever, so you want to send multiple packets at once. But if you send too many, you create congestion and add latency. If you send too few, you're not using the network to its fullest extent.

There used to be a problem called buffer bloat that David Taht recognized—too many buffers were causing bad internet performance. TCP algorithms alone weren't enough to solve this, so Linux added traffic control (TC) and fq-codel to help. Bandwidth is how much data you send per second, and round trip time (RTT) is how long data takes to send and come back. The challenge is that the distance between points often isn't symmetric, and more commonly, the bandwidth is very different in each direction. The bandwidth times RTT tells you how much data you have in flight that you've accounted for. You typically need fewer packets coming back, so you have less bandwidth in the return direction.

Bandwidth and Capacity

The 2.4 GHz band is divided into 20 MHz chunks. The Shannon-Hartley theorem states that available capacity measured in bits per second equals bandwidth (in megahertz) times log base 2 (because we're dealing with binary bits) of 1 plus the signal-to-noise ratio. For the most part, Wi-Fi is genuinely just taking turns—it's not bundling all signals together. The layers handle the turn-taking so the system knows it's receiving your specific signal.

Torrenting works by splitting data into many little chunks using UDP. You build up a file chunk by chunk, with many people seeding it. Different computers send different chunks to you, and your computer rebuilds the complete file. ISPs don't like torrenting because UDP will keep transmitting without the congestion control that TCP provides, so it's up to BitTorrent clients to manage this. Comcast and other ISPs sometimes throttle this traffic. Speed tests like Ookla just tell you how much bandwidth Ookla's servers can provide—you'll only ever get around 5 Mbps from Adafruit's servers, for example, regardless of your connection speed. If you multiply all the bandwidth plans by how much infrastructure can actually support, the oversubscription ratio is often in the triple digits.

DNS and Addressing

IP addresses in IPv4 are described in 4 bytes (written as dotted decimal numbers), while IPv6 addresses use 16 bytes (written in hexadecimal). Your router and IP address start with the same numbers because there's a default route address that defines your subnet. You get your IP address assigned through DHCP—after you connect to a network, it tells you what address to use, what route to use, and what DNS servers to use. Common DNS servers include 8.8.8.8 (Google) or 1.1.1.1 (Cloudflare), which are servers that map domain names to IP addresses.

What's Happening in My Project

My final project uses MQTT to create an IoT-enabled thermal printer that receives messages over Wi-Fi. When someone publishes a message to my Adafruit IO feed, the message travels through all the networking layers we've discussed. The MQTT library on my ESP32-C3 receives the message and triggers three simultaneous outputs: the NeoPixels do a chase animation in cyan, the I2S audio amplifier plays a 440Hz beep through the speaker, and the thermal printer prints the message.

Here's how the networking stack works in this system: The MQTT library (application layer) hands off packets to TCP on the ESP32-C3. TCP ensures the message arrives reliably and in order, then hands it to the IP layer which routes it from Adafruit IO's servers through the internet to my local network. The IP packets arrive at my router, which forwards them to my ESP32-C3's IP address via the MAC layer. The MAC and PHY layers on the ESP32-C3's Wi-Fi chip receive the 2.4GHz signal, demodulate it back to digital data, and pass it up through the stack.

On the sending side (my laptop or phone), when I use the HTML interface to publish a message, it makes an HTTPS POST request to Adafruit IO's REST API. That HTTP request gets handled by TCP, which chops it into packets and sends them through my device's IP layer, MAC layer, and finally the Wi-Fi NIC (network interface controller). The MAC layer on my laptop includes both a driver (part of the kernel) and firmware (a binary blob loaded onto the Wi-Fi card). The networking is symmetrical—the same layers exist on both my sending device and the ESP32-C3, just working in opposite directions.