Overview

This week brought my sensor board to life by implementing the input device functionality. After designing the PCB in Week 5 and fabricating it in Week 6, it was time to make the sensors actually work. The assignment required measuring something by adding sensors to a microcontroller board and reading them. I focused on getting both the phototransistor (light sensor) and NTC thermistor (temperature sensor) operational, using the XIAO ESP32-C3 to read analog values and convert them into meaningful physical measurements.

Understanding the Input Devices

Phototransistor: Measuring Light Intensity

The phototransistor (PT15-21C-TR8) is an optical sensor that changes its electrical conductivity based on incident light. Unlike a photoresistor which simply changes resistance, a phototransistor acts as a current amplifier - the base current is controlled by light photons rather than an electrical signal. When light hits the semiconductor junction, it generates electron-hole pairs that allow current to flow from collector to emitter. More light means more current, creating a measurable voltage across a load resistor.

In my circuit, I configured the phototransistor with a pull-up resistor to VCC (3.3V), creating a voltage divider. As light intensity increases, the phototransistor conducts more current, pulling the voltage at the analog input lower. The XIAO ESP32-C3's 12-bit ADC (0-4095) reads this voltage, which I then convert to illuminance in lux using a calibration formula.

NTC Thermistor: Measuring Temperature

The NTC (Negative Temperature Coefficient) thermistor is a temperature-dependent resistor that decreases its resistance as temperature increases. This inverse relationship follows the Steinhart-Hart equation, but for practical purposes, I used the simplified Beta parameter equation. My thermistor has a Beta value of 3950K, meaning its resistance-temperature curve follows a specific exponential relationship.

The thermistor is placed in a voltage divider circuit with a fixed resistor, creating a temperature-dependent voltage that the microcontroller's ADC can read. As temperature rises, resistance drops, changing the voltage divider ratio. By measuring this voltage and knowing the Beta parameter, I can calculate the actual temperature in Celsius.

Component Assembly and Testing

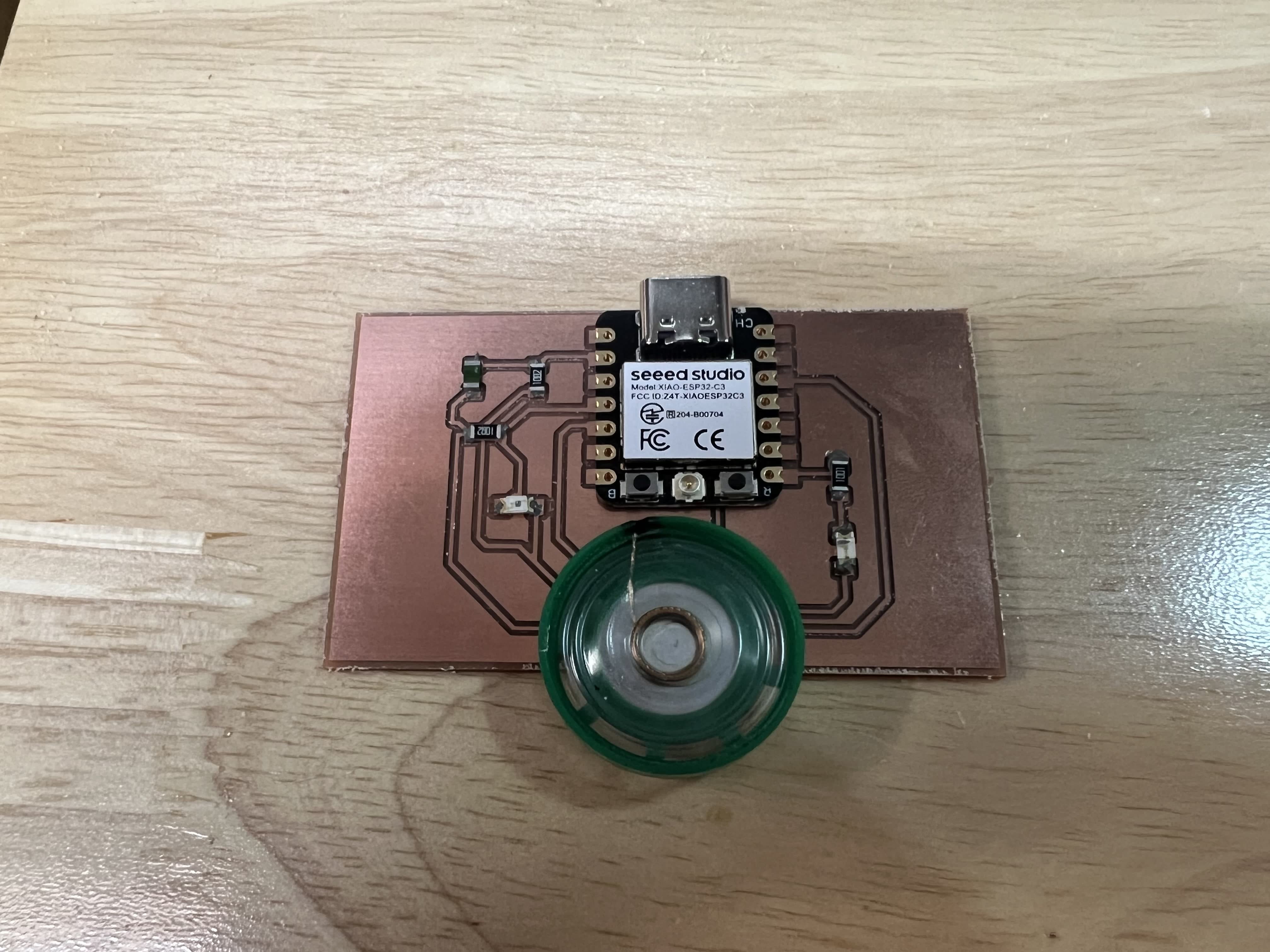

All components placed on the board, not soldered yet

After successfully milling the PCB in Week 6, I assembled the board by soldering all components. The XIAO ESP32-C3 provides a compact microcontroller platform with built-in WiFi and Bluetooth capabilities, though for this application I primarily needed its analog input pins. I switched to the ESP32-C3 not the RP2040 because of its excellent ADC performance and native support in the Arduino IDE.

Component placement followed standard assembly practice - starting with the lowest profile components (resistors) and working up to the tallest (the XIAO module itself). The phototransistor needed to be positioned where it could effectively sense ambient light, while the thermistor's location required consideration to avoid heat from other components affecting readings.

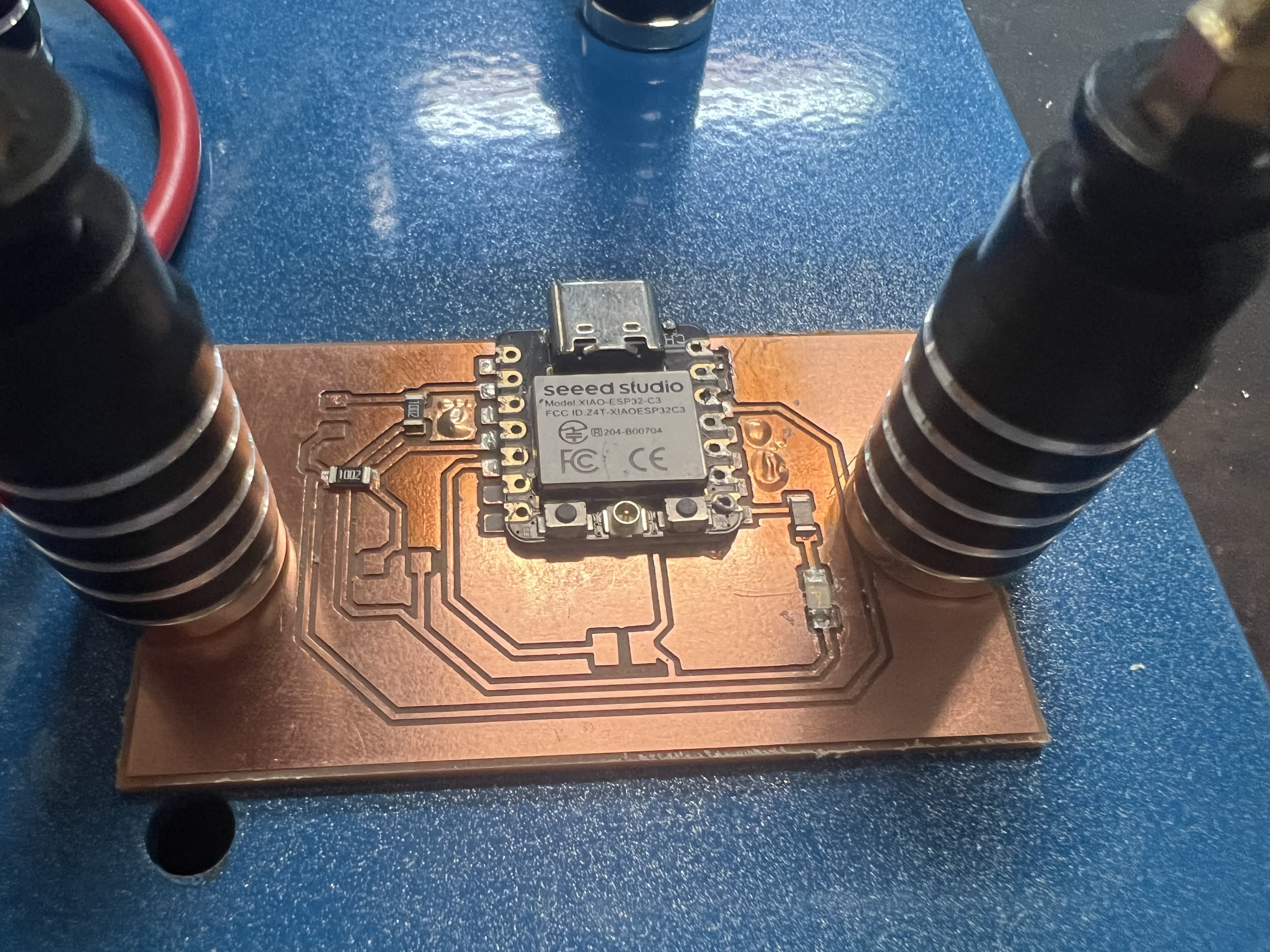

Soldering the components using solder paste

I used solder paste to solder the components, but the excessive heating made some copper pops up, but it does not affect the functionality of the board.

Sensor Testing

Temperature Sensor Response

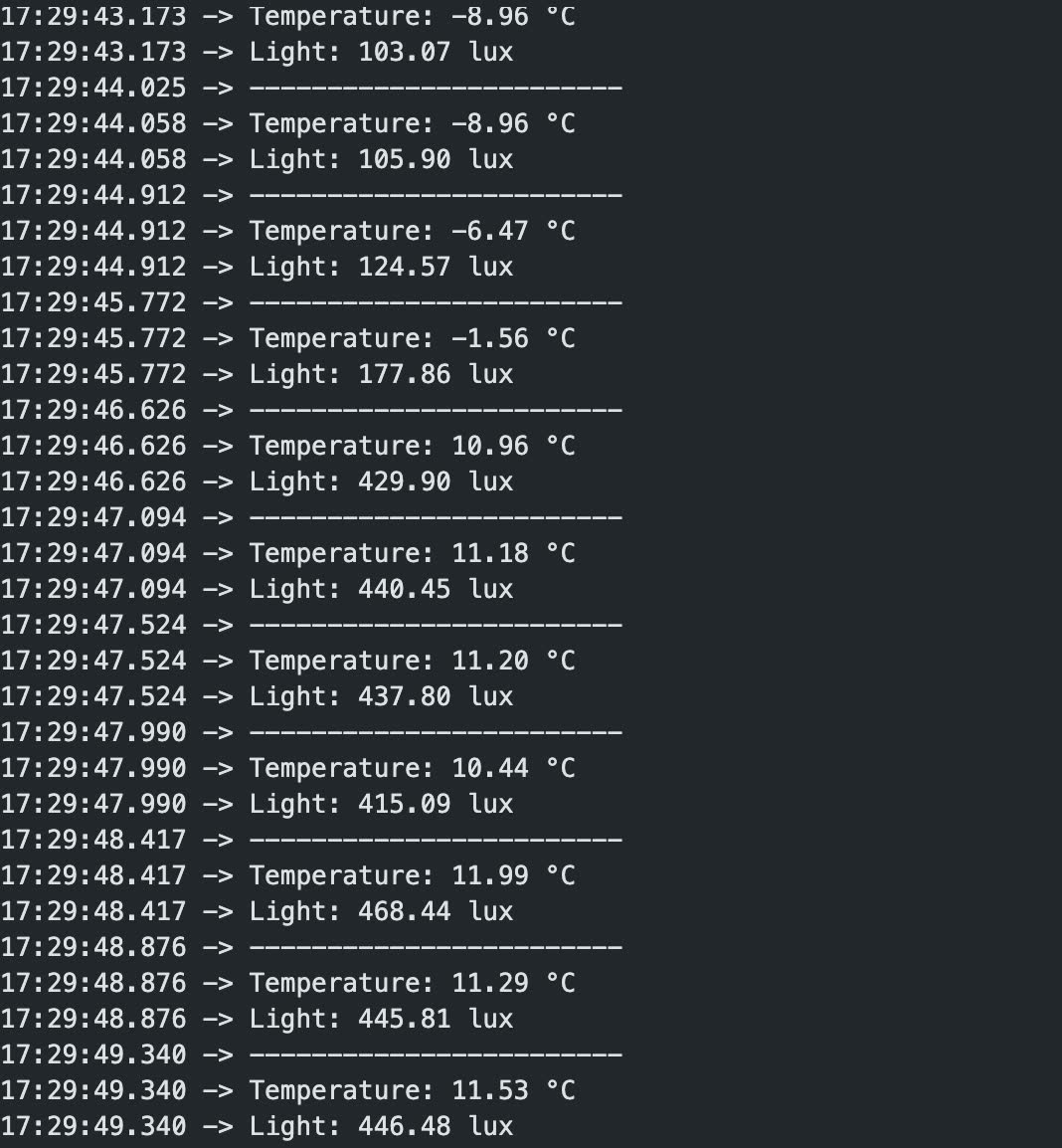

Temperature readings over time showing sensor response to environmental changes

Testing the temperature sensor revealed both its capabilities and limitations. The NTC thermistor responded quickly to temperature changes, tracking variations in room temperature as well as heat from my hand when placed near the sensor. The readings showed good stability, with minimal noise in the ADC values. However, I discovered an interesting challenge - the board itself generated heat during operation, particularly from the voltage regulator and microcontroller.

Light Sensor Response

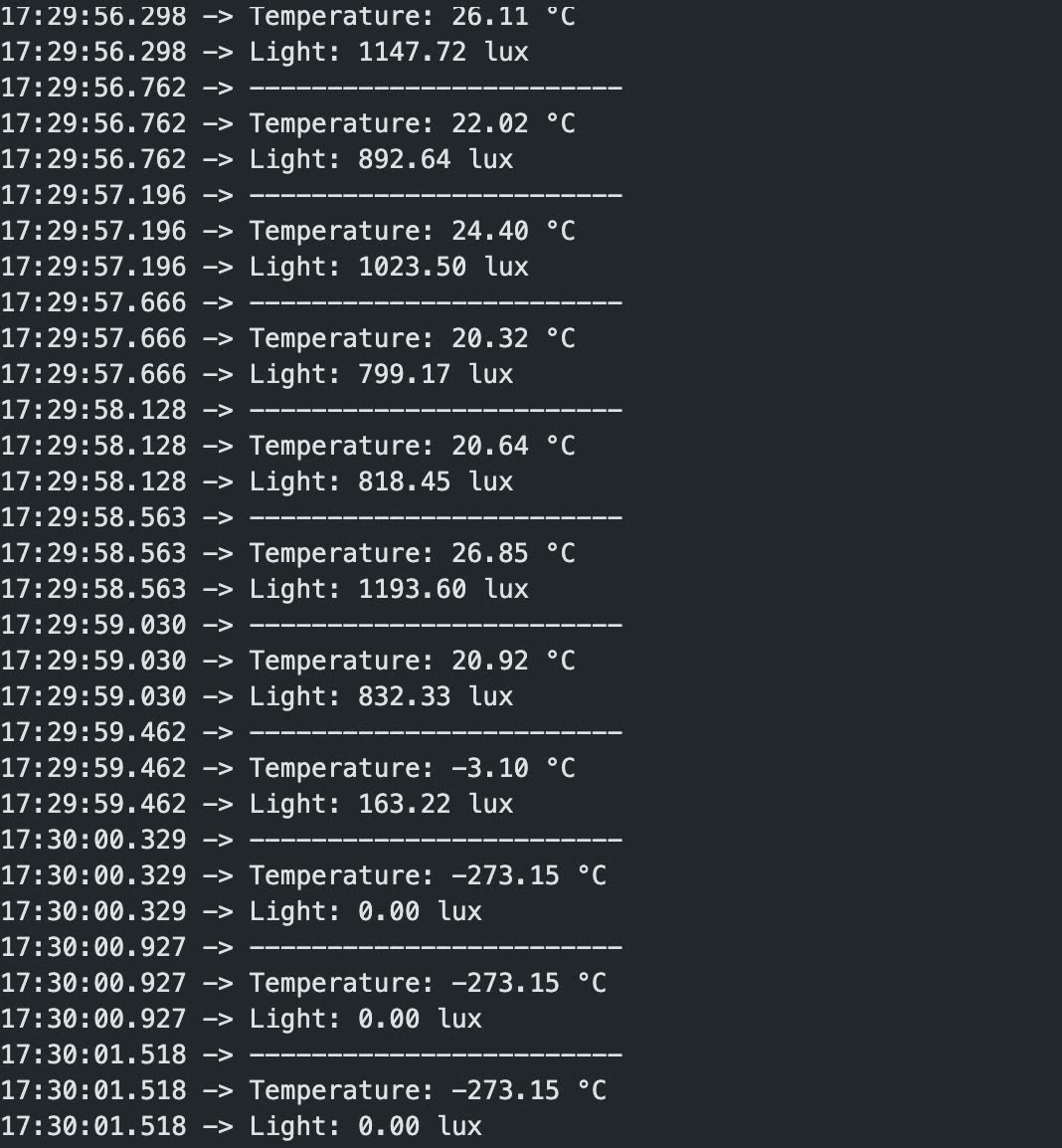

Light intensity measurements showing sensor response across different illumination levels

The phototransistor performed excellently across a wide range of lighting conditions. I tested it under various scenarios: complete darkness (under a covered box), indoor ambient light, direct desk lamp illumination, and bright sunlight from a window. The sensor showed good sensitivity, clearly distinguishing between these different light levels. The measurements in lux correlated well with expected values for indoor environments (50-500 lux for typical rooms, 1000+ for direct sunlight).

One advantage of the phototransistor over simpler photoresistors is its faster response time and better linearity. When I rapidly changed lighting conditions (like turning a lamp on and off), the sensor responded almost instantaneously. This makes it suitable for applications requiring real-time light sensing, such as automatic brightness control or optical communication.

Software Implementation

Reading and Processing Sensor Data

The Arduino code for reading the sensors demonstrates the complete signal chain from physical phenomena to digital measurements. For the temperature sensor, the process involves several steps:

// Read temperature from NTC thermistor

int ntcValue = analogRead(TEMP_PIN); // ESP32-C3: 0–4095

// Convert ADC value to temperature using Beta parameter equation

float celsius = 1.0 / (log(1.0 / (4095.0 / ntcValue - 1.0)) / BETA + 1.0 / 298.15) - 273.15;

Serial.print("Temperature: ");

Serial.print(celsius);

Serial.println(" °C");The thermistor calculation uses the Beta parameter equation, a simplified form of the Steinhart-Hart equation. The ADC reading (0-4095) represents the voltage at the divider midpoint. By knowing the reference voltage (3.3V) and the Beta value (3950K), I can work backward to calculate temperature. The equation accounts for the logarithmic resistance-temperature relationship of the NTC thermistor.

For the light sensor, the conversion is similarly multi-step:

// Read light from phototransistor

int lightValue = analogRead(LIGHT_PIN); // 0–4095

// Convert to voltage

float voltage = lightValue * 3.3 / 4095.0;

// Calculate photoresistor resistance

float resistance = 2000.0 * voltage / (3.3 - voltage);

// Convert resistance to lux using power law relationship

float lux = pow(RL10 * 1000.0 * pow(10, GAMMA) / resistance, (1.0 / GAMMA));

Serial.print("Light: ");

Serial.print(lux);

Serial.println(" lux");The light calculation converts the ADC reading to voltage, then calculates the sensor's resistance based on the voltage divider configuration. Finally, it applies a power law relationship (with gamma parameter) to convert resistance to illuminance in lux. The gamma value (0.7) and RL10 (resistance at 10 lux) are calibration constants that characterize the specific sensor's response curve.

Signal Processing Considerations

Both sensors exhibited some ADC noise - random variations in the least significant bits of the readings. For the temperature sensor, I implemented simple averaging over multiple samples to smooth out this noise. The light sensor was more tolerant of noise since illuminance typically changes relatively slowly (except for artificial light flickering at AC frequency, which the sampling rate averaged out).

The ESP32-C3's 12-bit ADC provides excellent resolution - 4096 discrete levels across the 3.3V range, or about 0.8mV per step. This resolution is more than adequate for both sensors, allowing temperature resolution better than 0.1°C and light level discrimination of a few lux. The ADC's built-in attenuation settings could extend the input voltage range if needed, though the default 0-3.3V range worked well for my voltage divider circuits.

Key Learnings

Sensor Physics and Electronics

Working with physical sensors reinforced the connection between electronics theory and real-world measurements. The phototransistor's quantum photoelectric effect, the thermistor's thermally-activated conductivity, and the way these physical phenomena manifest as voltage signals that an ADC can digitize - understanding this complete chain is essential for effective sensor integration. Each sensor has unique characteristics (response time, linearity, temperature dependence) that must be considered in both circuit design and software.

Calibration and Characterization

Both sensors required calibration constants (Beta for temperature, gamma and RL10 for light) to convert raw resistance values to physical units. These parameters are typically provided in datasheets, but achieving accurate absolute measurements often requires individual calibration against reference instruments. For my application, relative measurements were sufficient, but applications like precision thermometry or photometry would need careful calibration procedures.

ADC Performance and Resolution

The ESP32-C3's ADC proved to be quite capable for analog sensing. The 12-bit resolution provided adequate precision, and the stable voltage reference kept readings consistent. However, I learned about ADC limitations too - some nonlinearity at the extremes of the range, sensitivity to power supply noise, and the importance of proper analog ground routing. Understanding your microcontroller's ADC specifications and limitations is crucial for reliable sensor readings.

Technical Specifications

| Parameter | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microcontroller | XIAO ESP32-C3 | 160MHz RISC-V, 12-bit ADC |

| ADC Resolution | 12-bit (0-4095) | ~0.8mV per step at 3.3V |

| Temperature Sensor | NTC Thermistor, β=3950K | 10kΩ at 25°C |

| Temperature Range | 0-50°C | Typical indoor/lab conditions |

| Temperature Resolution | ~0.1°C | Limited by ADC resolution |

| Light Sensor | Phototransistor PT15-21C-TR8 | Visible spectrum sensitivity |

| Light Range | 1-10,000 lux | Dark room to bright daylight |

| Response Time | <10ms (both sensors) | Fast enough for real-time monitoring |

| Sampling Rate | Variable (code-controlled) | Limited by serial output in demo |

| Power Consumption | ~80mA @ 3.3V | Mostly from ESP32-C3 module |

Future Improvements

With both sensors now operational, several enhancements could improve the system. Implementing digital filtering (moving average or Kalman filter) would reduce noise and provide smoother readings. Adding temperature compensation for the light sensor would improve accuracy, as phototransistor sensitivity varies slightly with temperature. For the thermal issue, a redesigned PCB with better thermal isolation or active cooling could provide more accurate ambient temperature readings.

The sensor data could also be used in more sophisticated ways - logging to SD card for long-term environmental monitoring, wireless transmission via the ESP32's WiFi/Bluetooth capabilities, or integration into a home automation system. The combination of temperature and light sensing enables applications like smart thermostats, automated greenhouse control, or circadian rhythm lighting systems.