Final Project

For my final project, I designed a walking “luggage”. I have split the documentation into two parts. First, I provide a day-by-day “journal” of the process, including failures, successes and learning. Then, I answer some of the the questions posed directly.

Journal

[11/2] Inspiration

For my Week 1 Assignment, I described a project I was not entirely happy with. There were a few reasons for that. One major reason was that I wanted to make something big (which I don’t have a lot of experience with). After weeks of agonizing over what to make, I asked my wife what she thought, and withing 5 minutes she had the perfect idea.

This is The Luggage from the late Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series of books. The Luggage has many legs and can hold many things, but above all is a true companion.

[11/2] Initial thoughts

I cannot make The Luggage, because it has too many legs and also because it is sentient. But I think I can make something similar to The Luggage.

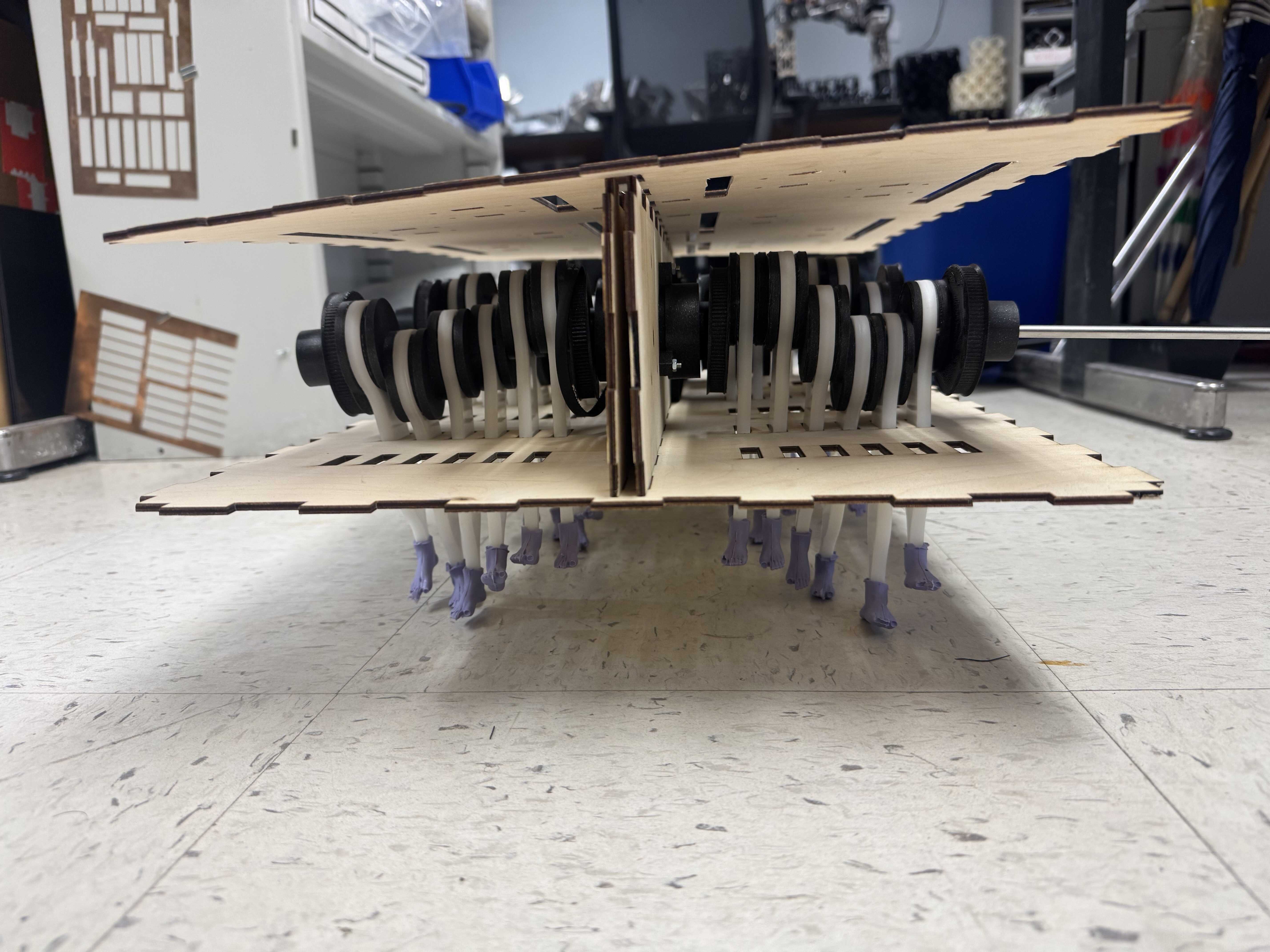

My version of The Luggage will consist of a box, which will be just a box, and some number of legs. I don’t want to make each leg independently controlled because that will limit the number of legs I can make. Instead, I plan to build a few axles with legs attached. They could be similar to camshafts, or they can simply have the legs attached directly, and spin them around like bristles on a vacuum cleaner. The legs themselves can be injection-molded, but will probably have to have a solid core to support meaningful weight in the box. I want my luggage to be able to turn, so I will include two sets of axles, and rely on slipping to make turns, like continuous track vehicles do. Each set of axles will turn together, so I can connect each set together with toothed belts, and have the whole system operate using only two (geared) motors. At this point, it’s probably evident to the reader that I am not a mechanical engineer, which is why I’m so excited about this project.

I feel much more confident about the electronics and software portions of the project. To enable easy testing of the mechanical components, I will initially put a radio onboard so that I can move the luggage around with a controller (like an RC car). If I can get to a point where that works well, I will attach a camera and train a very simple model to recognize silhouettes. When there is exactly one silhouette in view, I will create a control loop that tries to keep the silhouette centered and of a particular size. That way, my luggage should be able to follow me around.

[11/3-11/10] BLDCs

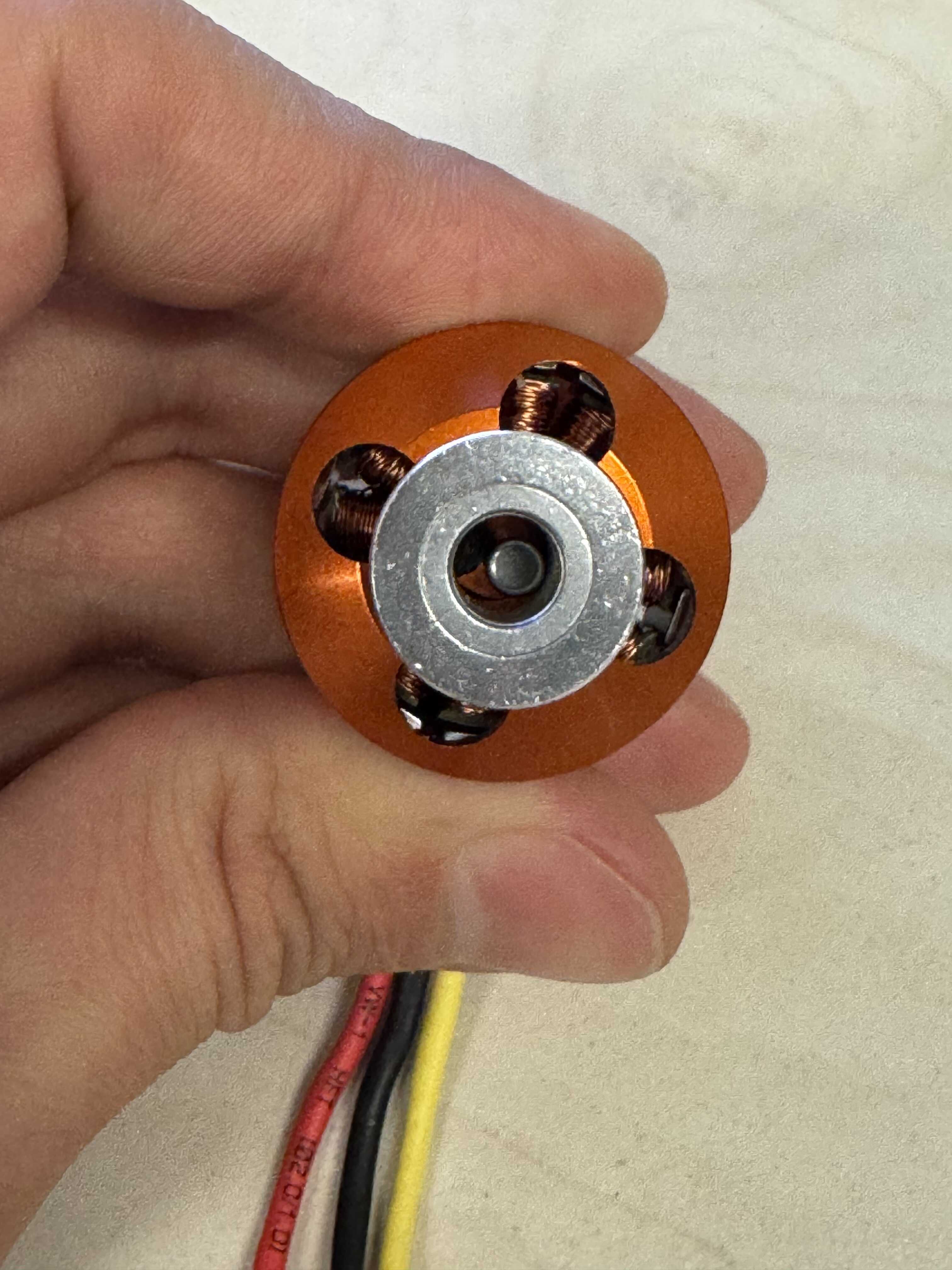

For output devices week, I explored BLDCs as a means of driving the system. I chose BLDCs because motor position is irrelevant for this project. My findings are documented on my Week 9 page.

[11/5-11/12] Molding and casting

I plan to mold the boots for the machine. I prototyped the process for molding and casting week. My findings are documented on my Week 10 page.

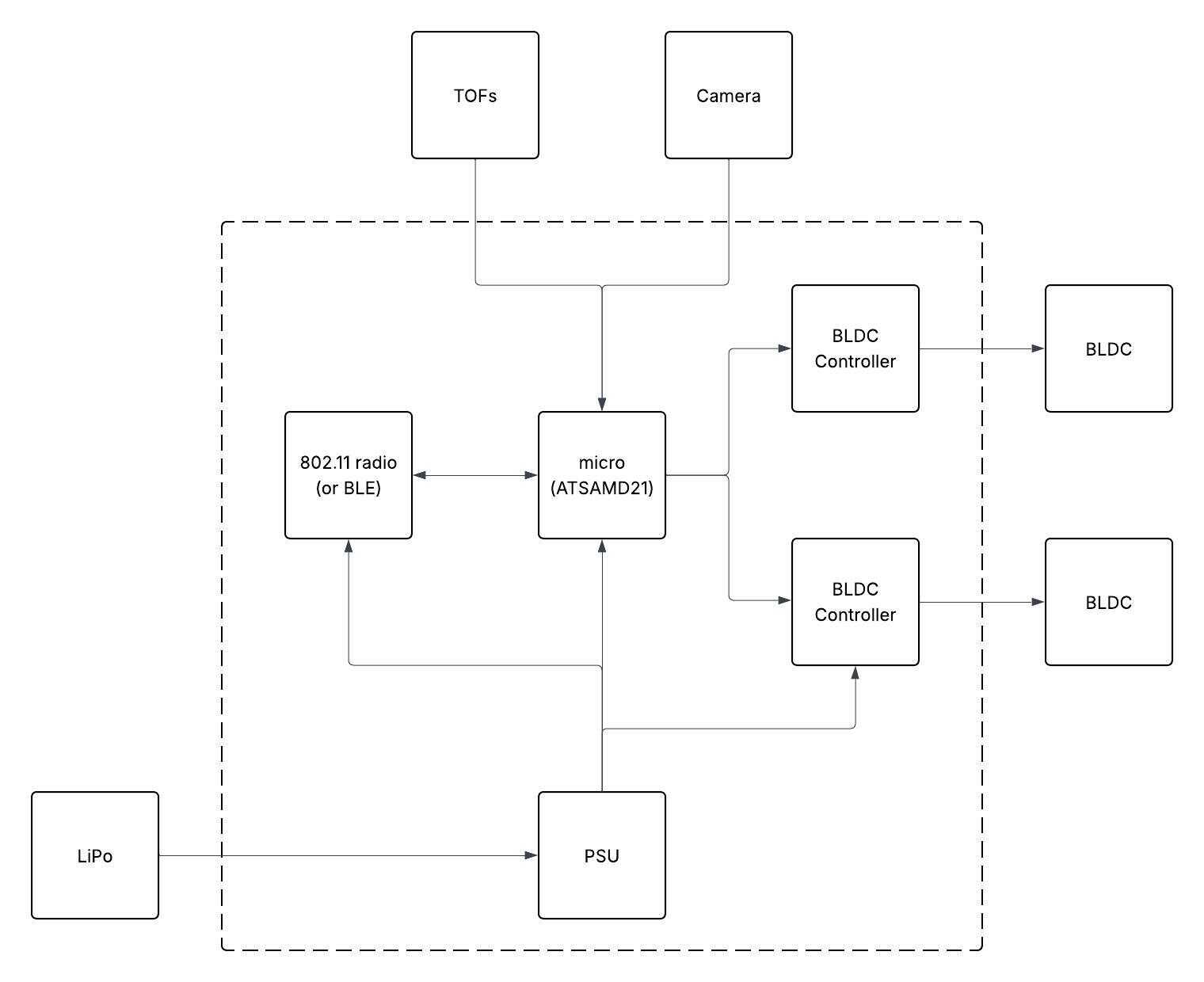

[11/17] Initial electronics block diagram

An initial block diagram for the electronics is given in Figure 2. The BLDCs will drive the legs through closed belts. The axles will be attached through bearings to a wooden or acrylic frame.

[11/17] Plan of action

Before machine week, I prototyped the BLDCs and the casting and molding process. I will not work on the final project until machine week is complete. After that, I will focus on the mechanicals first, because I am confident in the electronics and software.

Plans Are Worthless, But Planning Is Everything

– Dwight D. Eisenhower, maybe?

Here’s my current plan of action:

- 11/20 - 11/24: CAD (frame with bearings, axles, legs, boots for casting and molding)

- 11/24 - 11/26: 3D printing, casting and molding, testing

- 11/26 - 11/30: Thanksgiving (hoping mechanicals don’t bleed into it)

- 12/01 - 12/02: Schematic and PCB design

- 12/02 - 12/03: PCB Fabrication

- 12/04 - 12/05: Firmware

- 12/05 - 12/06: Software

- 12/07: Break

- 12/08 - 12/12: Integration

- 12/13 - 12/14: Bonus Features (e.g. motion detection)

- 12/15: project presentation

[11/29-11/30] Mechanism CAD

Getting started only slipped by 9 days - not so bad. (Those 9 days were spent on my final project for 6.2540; I mention it because I think it turned out nicely, and will add a link here when it’s available.)

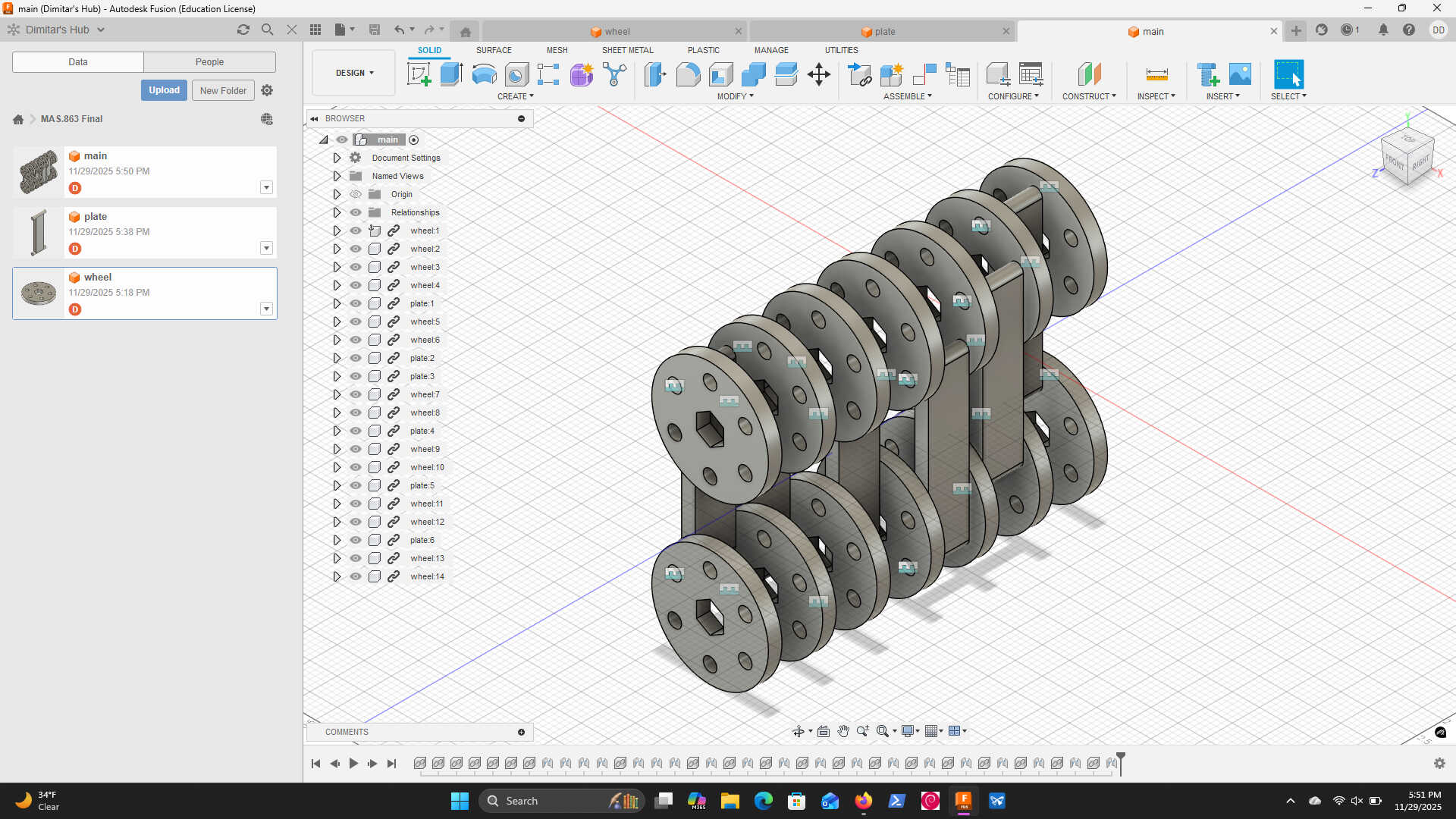

As Thanksgiving was winding down, I sat down to CAD up the mechanism I had had in my head for a few weeks. It consists of “plates” that hold one leg each, connected to four wheels each. Adjacent plates share wheels, but at a π/3 offset. 6 plates/legs (14 wheels) ensures that all legs are at different positions. My first draft in shown in Figure 3

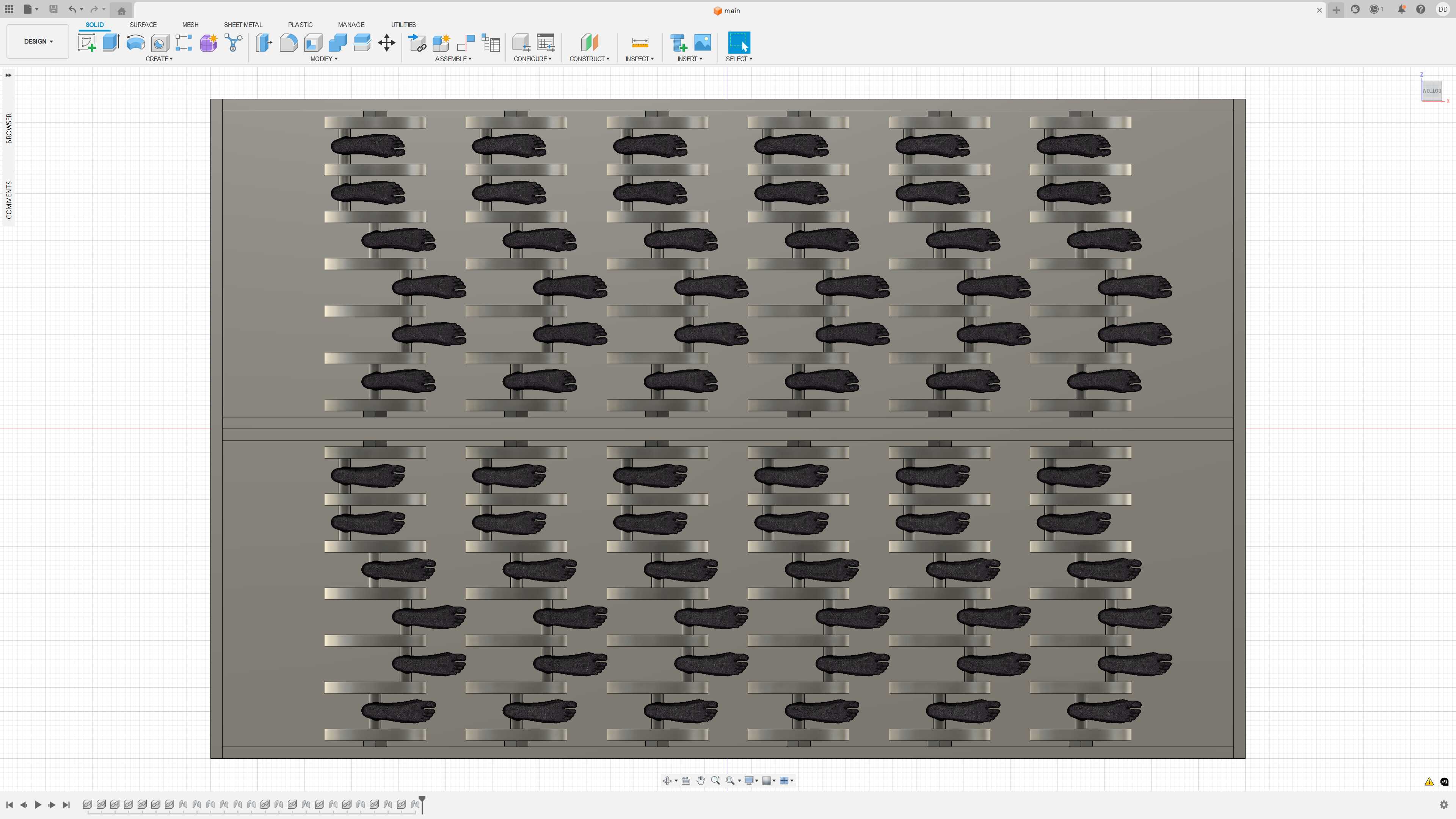

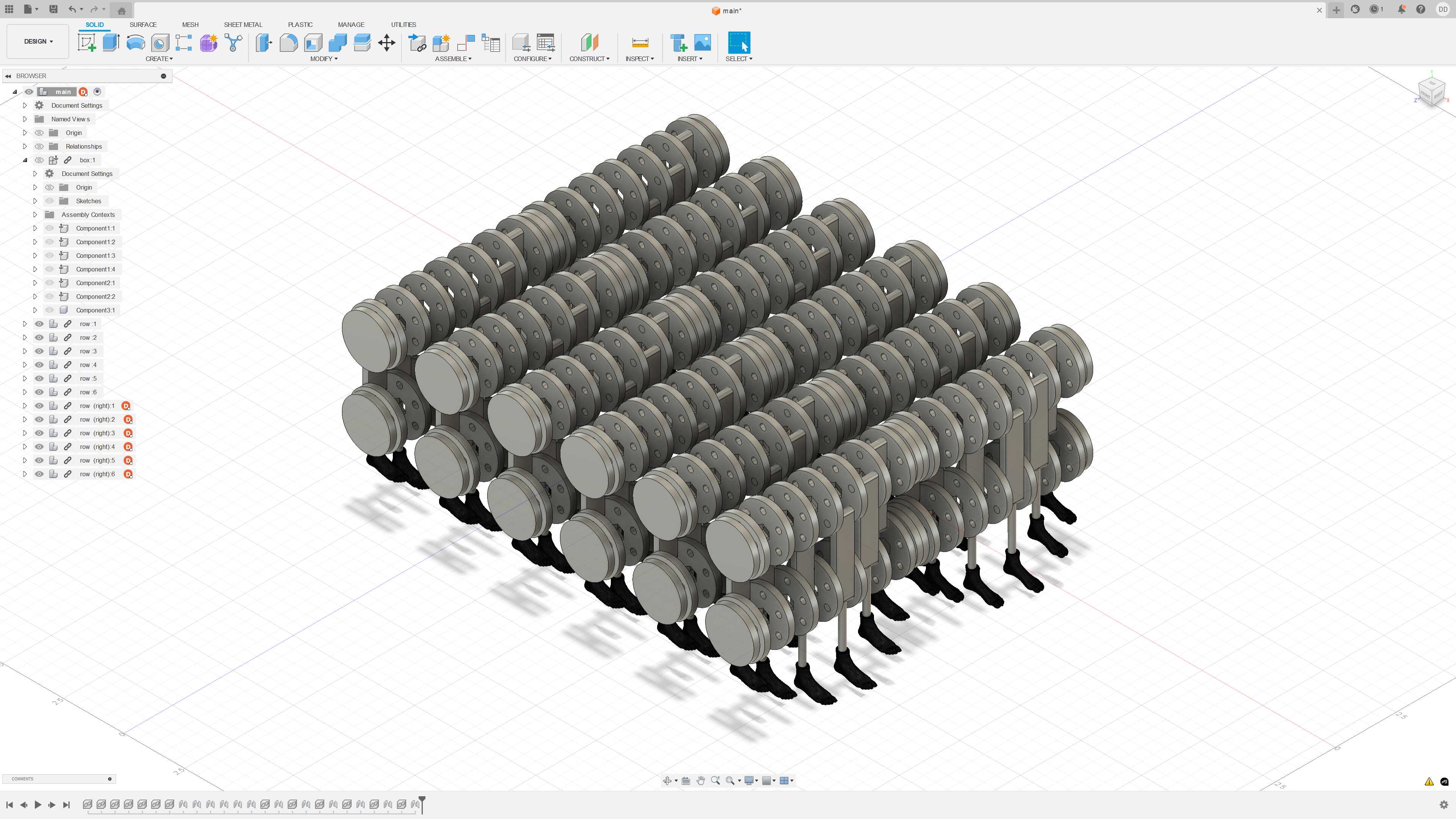

The next day, I put together CAD for the full system around this mechanism. For each side, I used 6 rows of 6 so that each row and each column on each side has a leg down at each phase. Miranda had found this 3D model for me earlier: https://cults3d.com/en/3d-model/various/feet-model-3d-pies-maniqui. I downloaded it and chopped it into left and right. I hope to make my own eventually, but this is a great placeholder for now. I also used placeholders for the bearings. I constrained the whole design to 22" x 14" x 9" (incidentally, the size of a standard carry-on). The results are shown in Figures 4-8.

[12/1] Prototyping

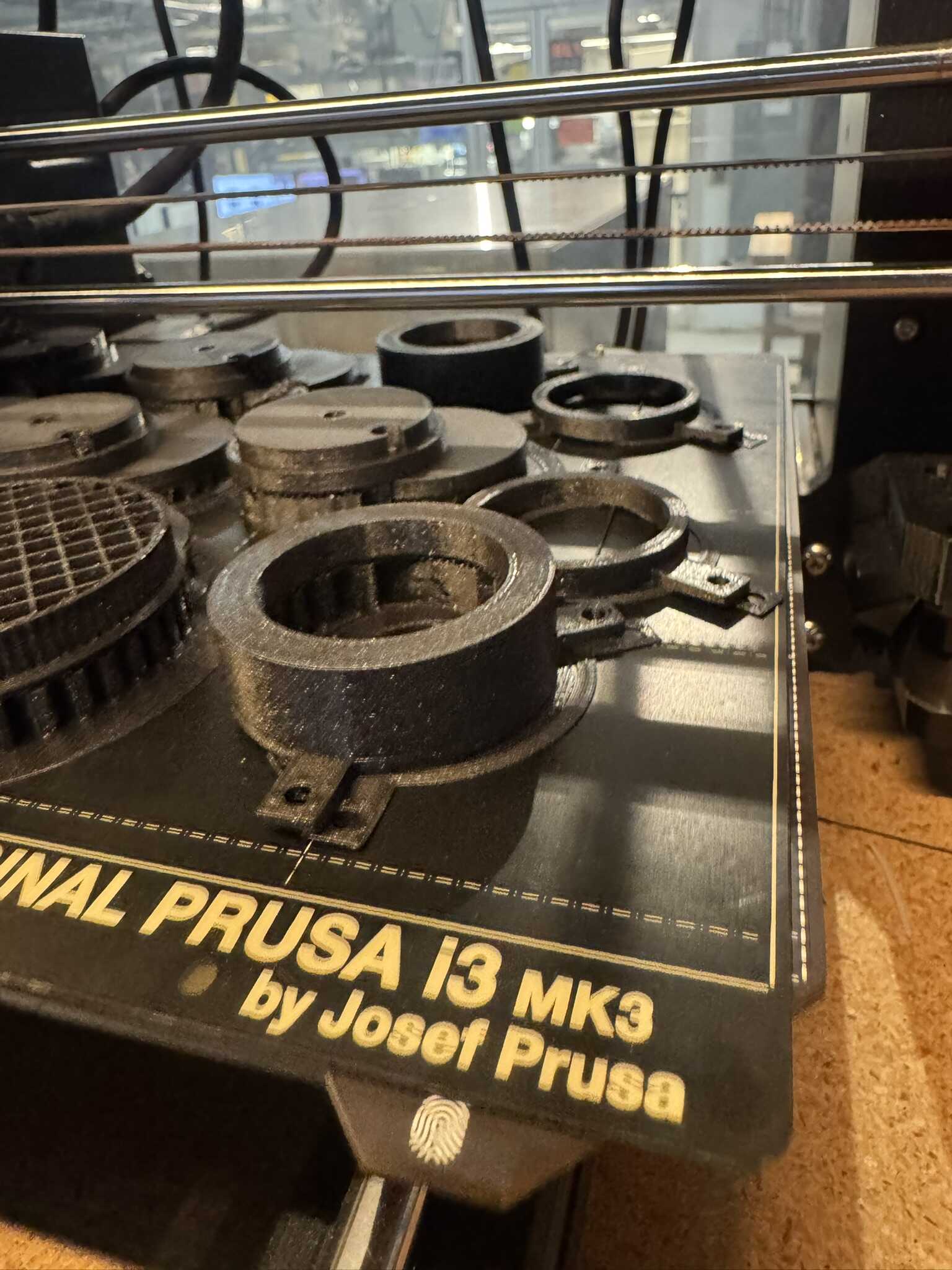

The next order of business was figuring out the bearings. I had never used a bearing in my life. So, I talked to Jake and Quentin, who recommended 625’s. I incorporated them into the CAD. I also designed mounts for them, and fasteners for the existing mechanism.

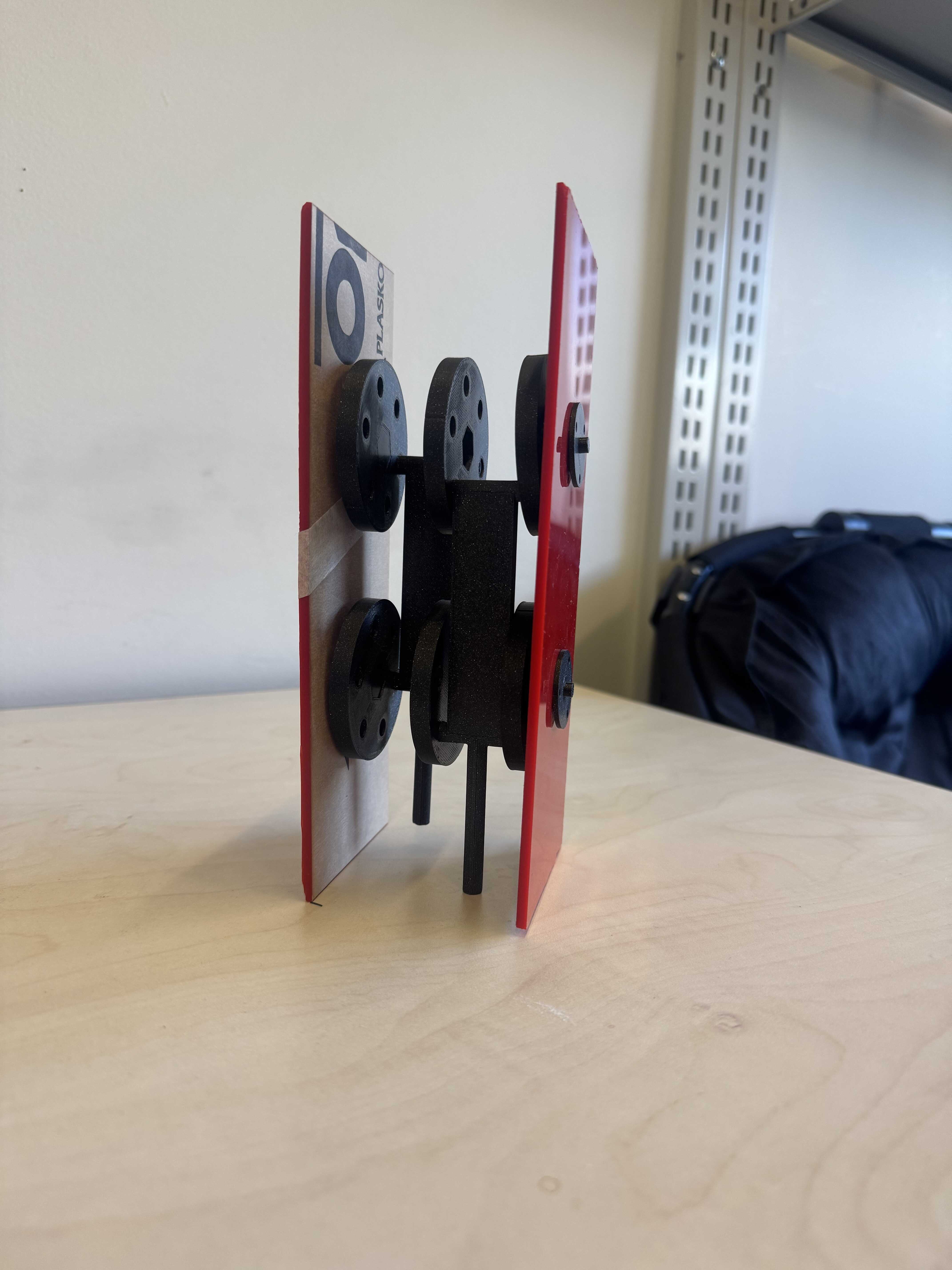

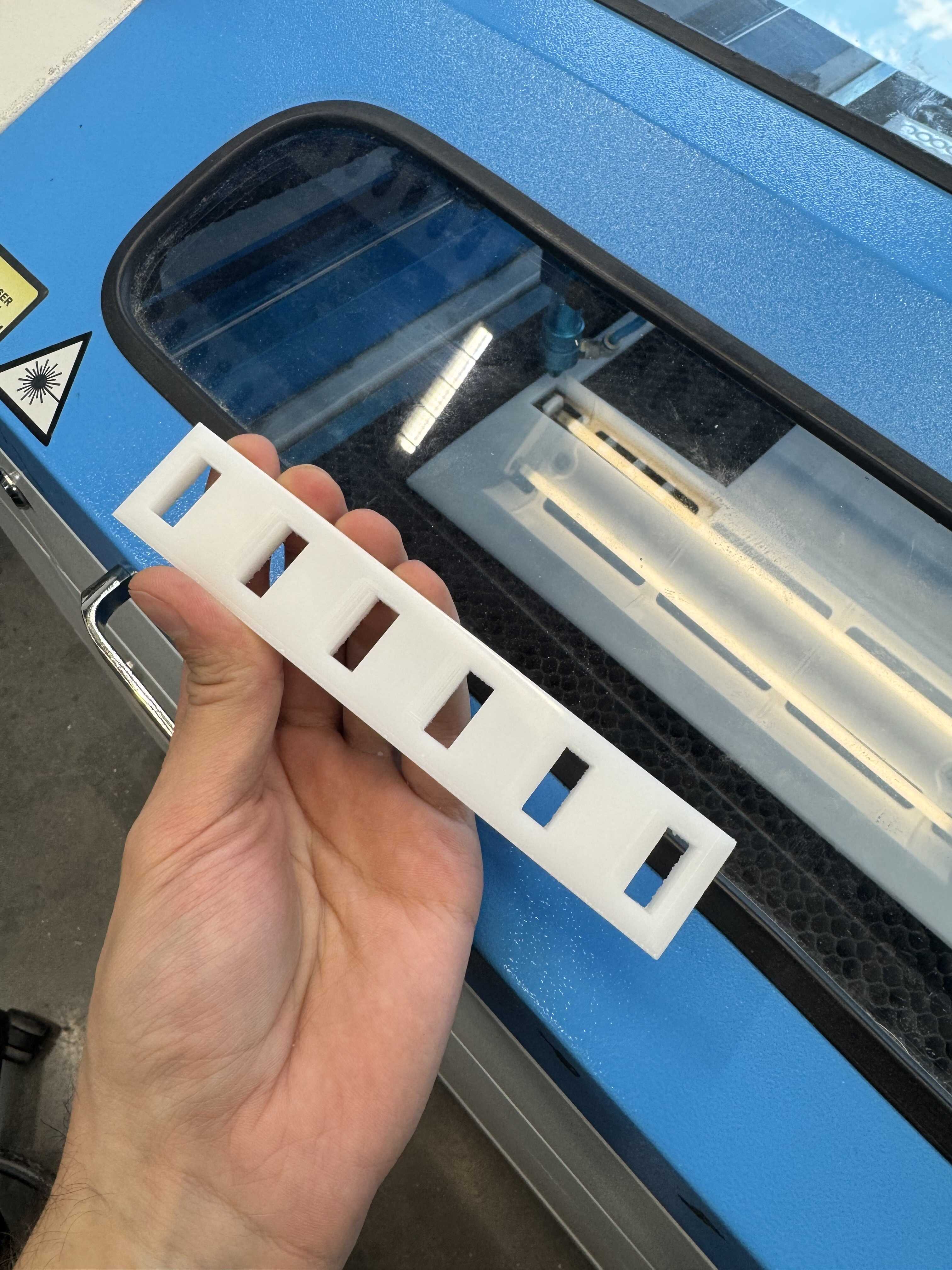

I then 3D-printed two plates, 6 wheels, 4 sets of bearing mounts, and enough fasteners. I laser cut two sections of the box on acrylic (one cracked, excuse the tape) and put everything together. The result is shown in Figure 9.

I had not added enough tolerance to the holes in the wheels, so they don’t spin. The next step would be to cut a few to find the perfect size. It occurred to me however, that for such a flat thing, laser cutting would be easier. If I use Delrin, I’ll get some natural slipperiness too, which will help. So, that’s the next step on this thread.

[12/2] Con rods

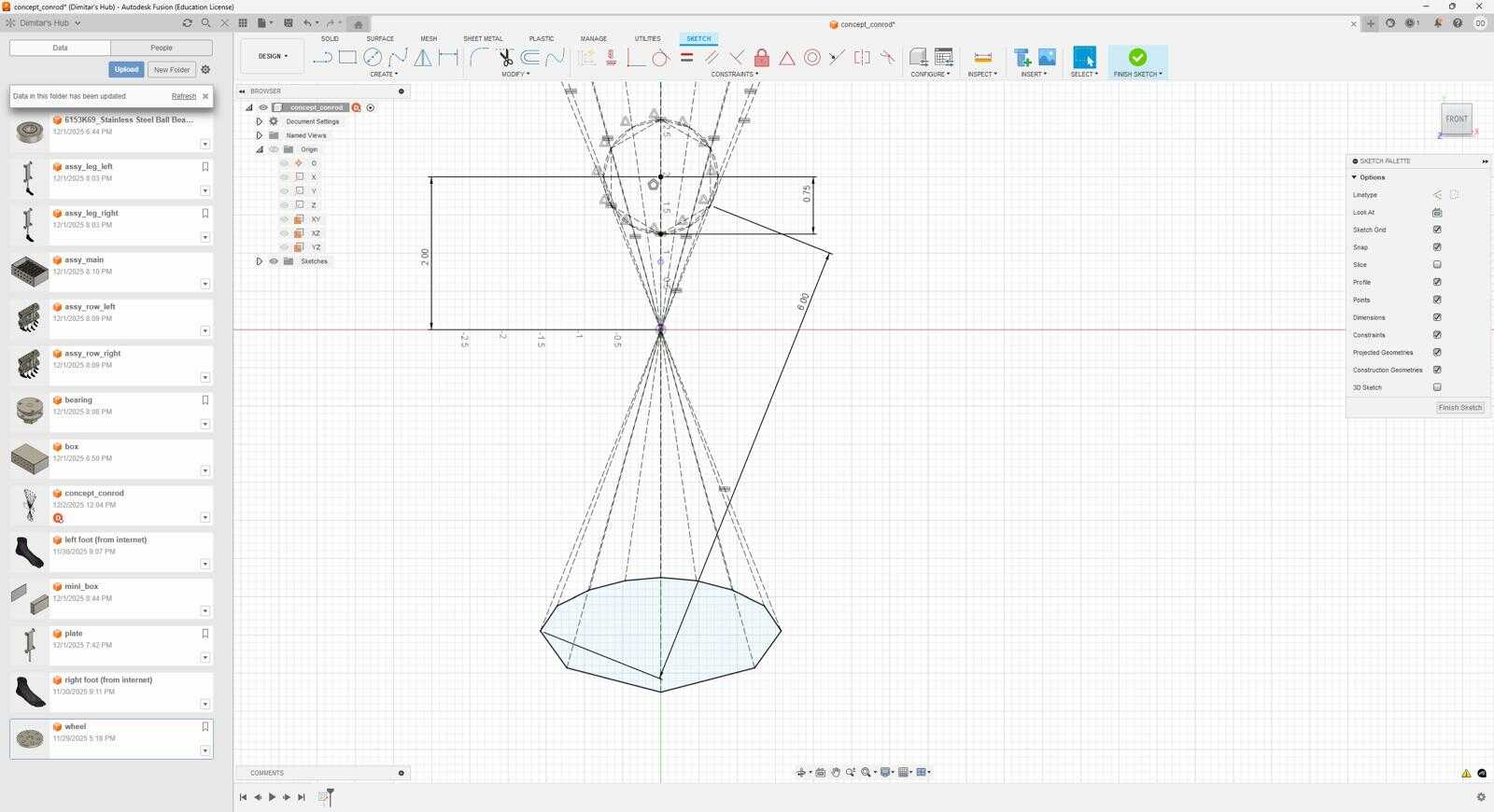

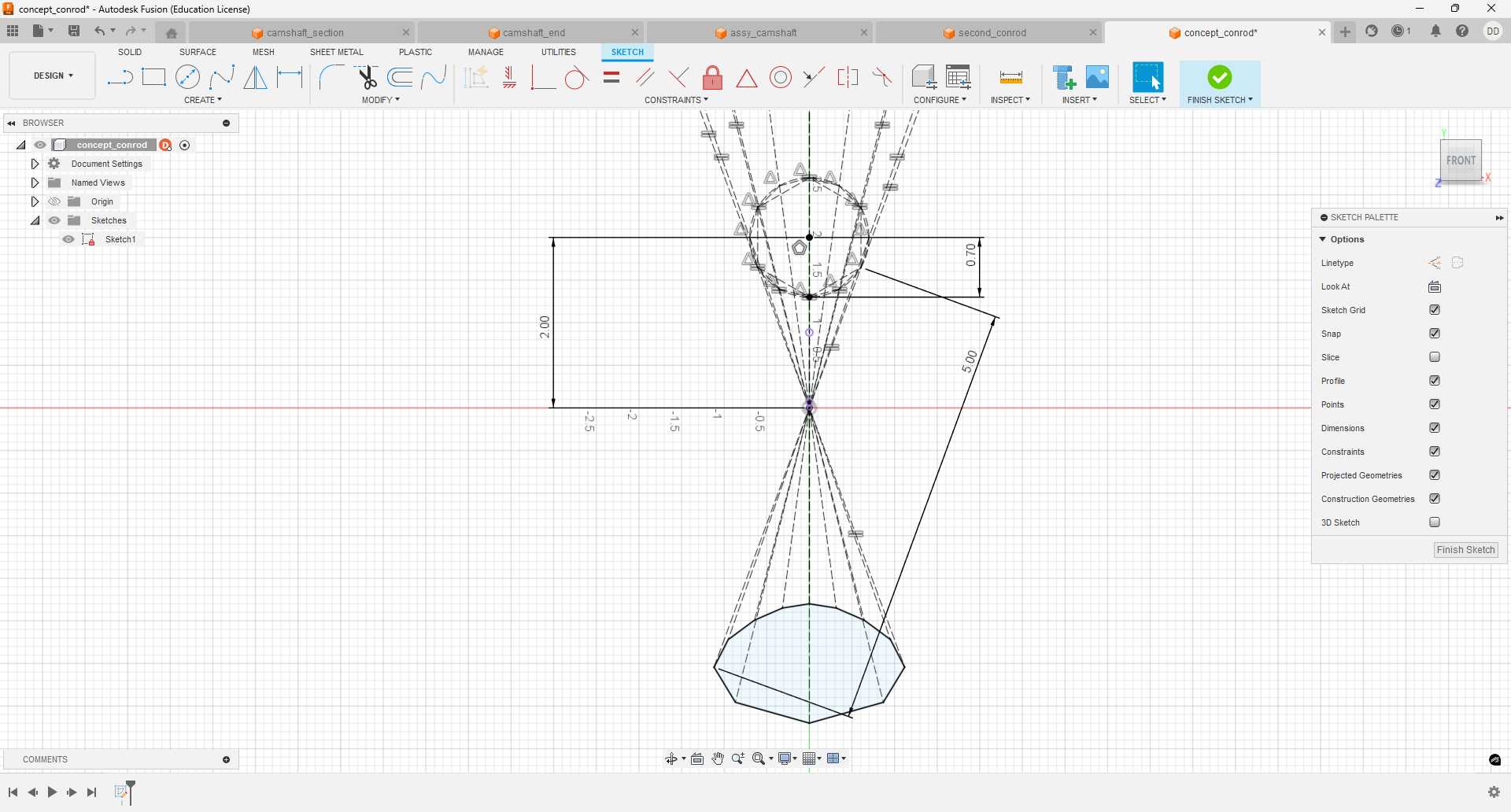

However, in talking to Jake about bearings on Monday, he gave me a much better idea - con rods. I sketched the concept as I understood it below:

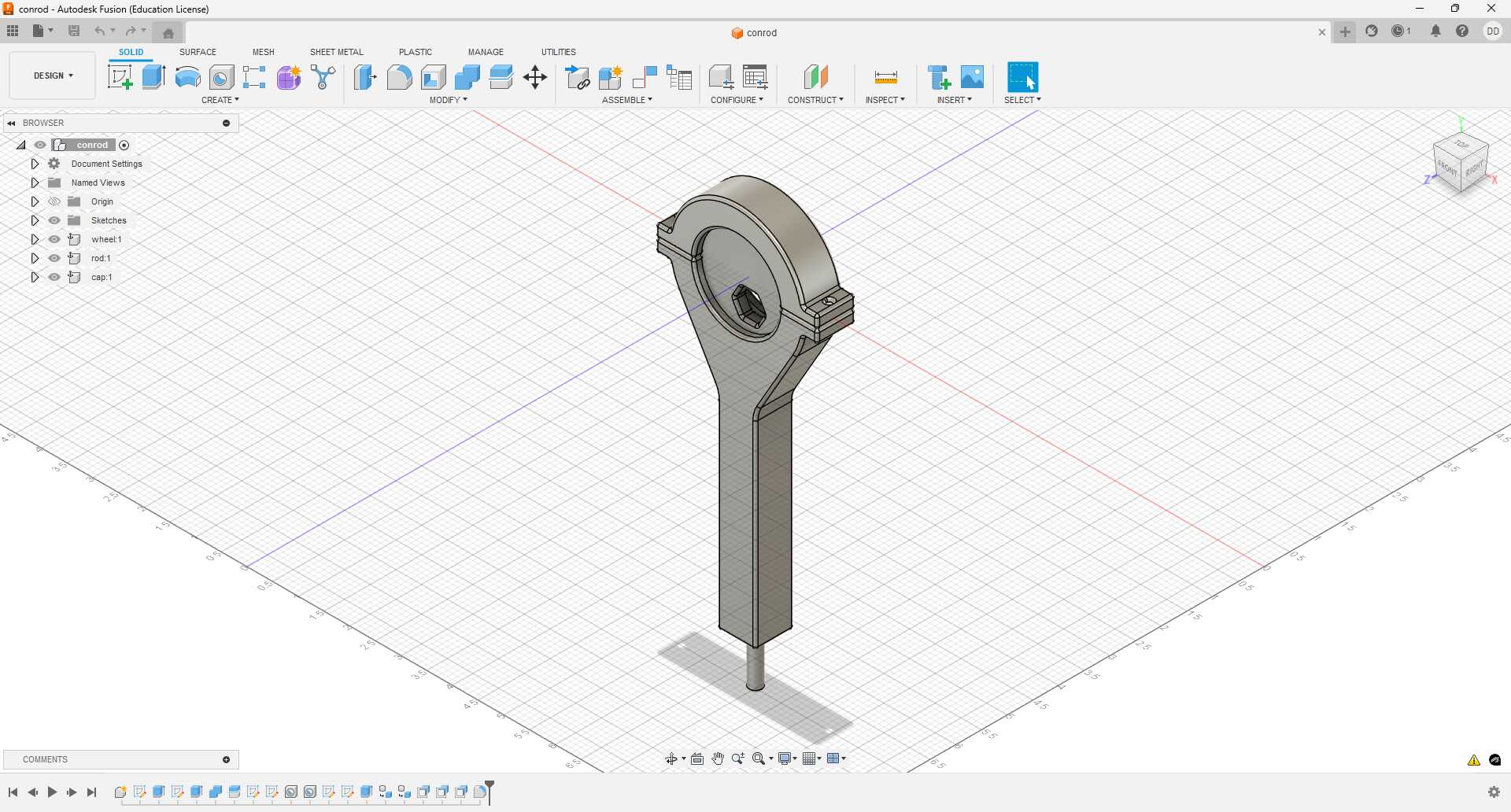

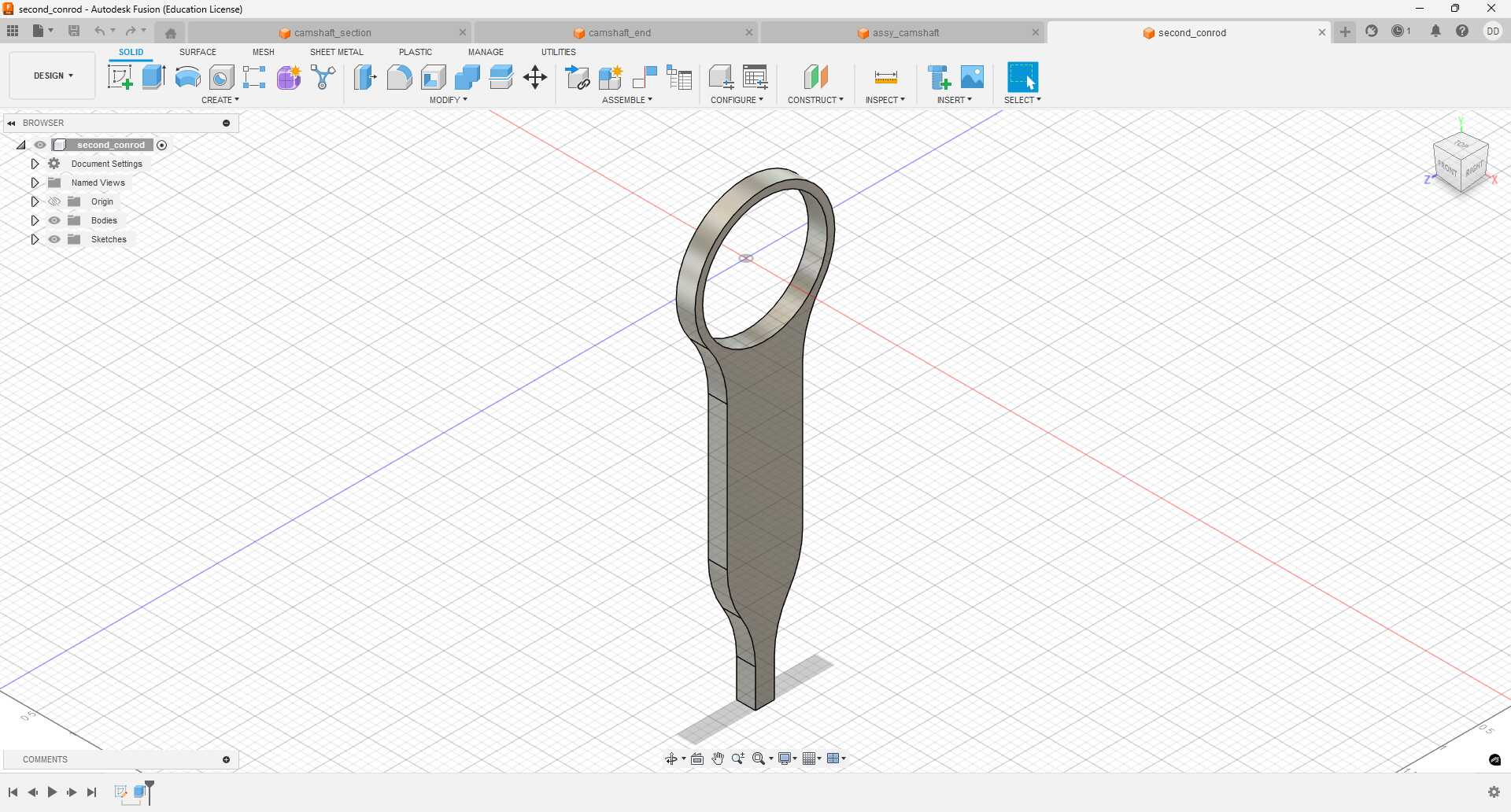

For the same rotation radius at the wheel (0.75in), I get a much nicer shape of motion at the end! Convinced, I CADed up my idea of what a con rod is:

And I printed it (with a makeshift axle):

Works great! (Though I have not yet designed the critical pivot point.) I did manage to crack the cap when I tried to use an M3 screw, which I had tried to design for using the built-in presets in Fusion. I just used an M2 instead, but this will be worth exploring.

There is an issue here with size. In the previous design, the width of the mechanism when looking at the box from the side stays constant. I just had to make sure it’s under 3" (the pitch of the legs). Here, the mechanism moves during rotation. The safest option it to keep the full motion under 3" (accounting for the flanges, which can perhaps be removed). However, adjacent legs will only be π/3 off, so this is conservative. At the same time, it is beneficial to make the mechanism as large as possible to maximize the turning radius. I will play with this more to find the optimal dimensions.

[12/2] Belts

Another critical component of the mechanics which I have absolutely no experience with is the belts. Jake recommended GT2 belts and pointed me to his wonderful blog post: https://ekswhyzee.com/2019/04/09/gt2-belt-rotary-cad.html. I tried designing a pulley using those instructions:

As I moved to the cutting step, Quentin introduced me to the GT2 Timing Pulley Generator plugin for Fusion. I ended up using that in the end. I added a hexagonal hole in the middle so it can mate with my makeshift axle above, but made an off-by-2.54 error. The printed pulley is shown below:

[12/3-12/4] RP2354

Over the next few days, I had limited opportunities to work on my project. I had originally intended to finish all the mechanical tasks before tackling hardware and software, because I have more experience with hardware and software. However, I signed up for PCB engraving for wildcard week. So, it felt natural to prototype and design my boards next.

For comms, I decided to use nRF24L01+’s, so that I have flexibility in designing a MAC that makes sense for the application. For the micros, I have a lot of technical flexibility (I just need SPI and PWM). The micros I have used so far in the class are:

- RP2040 in a XIAO

- ATSAMD21E18 (twice)

- AVR32DU14T

- ESP32S3 in a XIAO (twice)

I was initially leaning towards the ATSAMD21E18, because it has built-in USB and I enjoyed using it. I was also considering the RP2040, which is overpowered for this application, but lets me play with the PIOs. But then during the wildcard lecture, I was reminded of the RP2350 (which has even more PIOs). When this chip was announced in 2024, I was happy to see a commercial RISC-V micro that wasn’t an ESP32. I had been looking forward to learning more about the chip, and this seemed like a good opportunity to do that.

I decided to do a chip-down version instead of using a XIAO. Not only does this let me practice laser engraving, but allows me to create a nice form-factor for my “dongle” board. I was delighted to learn about the RP2354 chips, which have 2MiB of flash packaged in. Finally, I had the choice between the 60-pin RP2354A and the 80-pin RP2354B. I chose the RP2345A because even that has way more pins than I need.

The datasheet for the RP2350 family can be found here: https://pip-assets.raspberrypi.com/categories/1214-rp2350/documents/RP-008373-DS-2-rp2350-datasheet.pdf. It is very well written, and I spent more time than I should have perusing through it. Raspberry Pi also offer a hardware design guide, which I read carefully: https://datasheets.raspberrypi.com/rp2350/hardware-design-with-rp2350.pdf. I downloaded the KiCAD files for the reference board from here: https://datasheets.raspberrypi.com/rp2350/Minimal-KiCAD.zip.

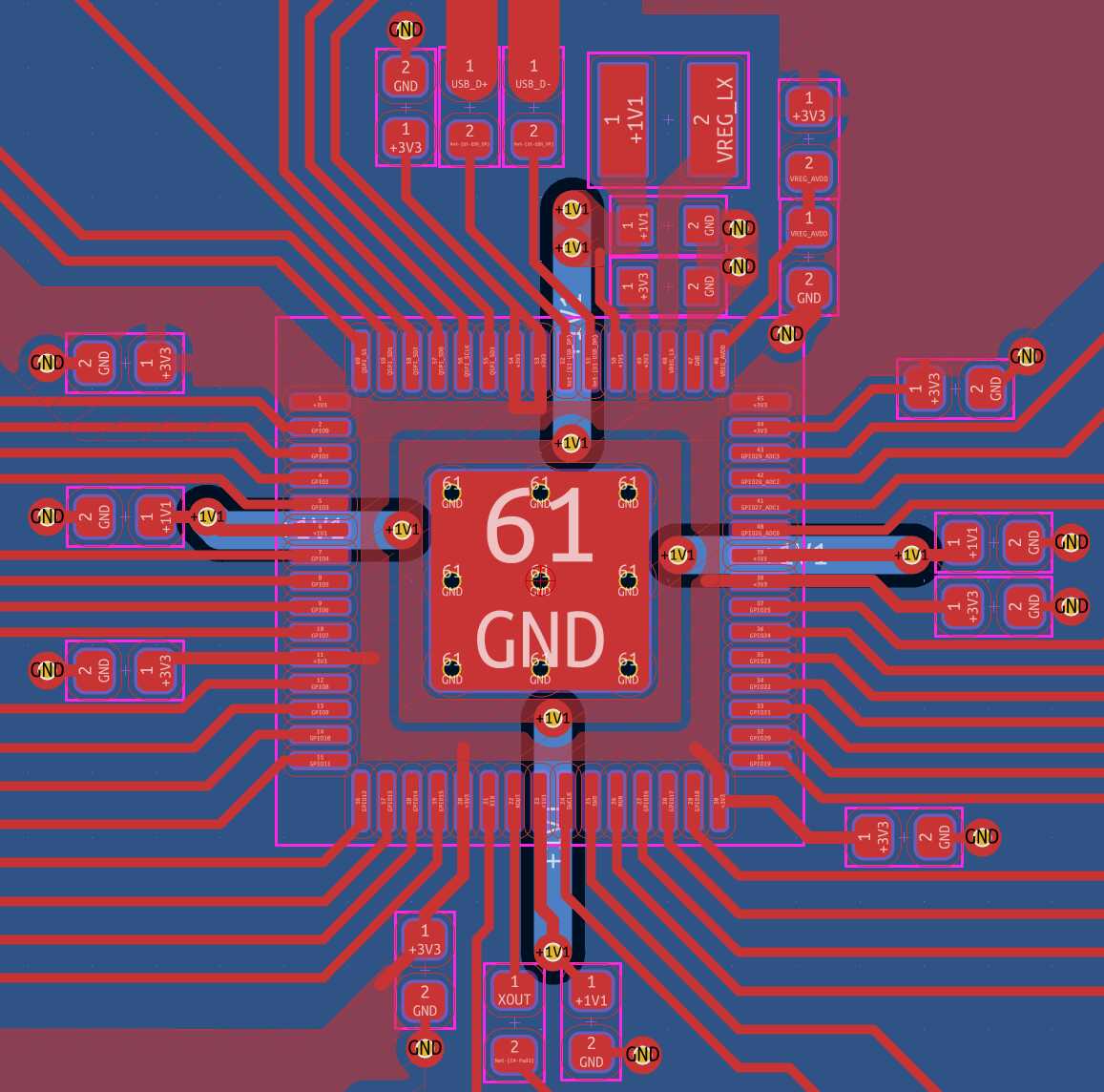

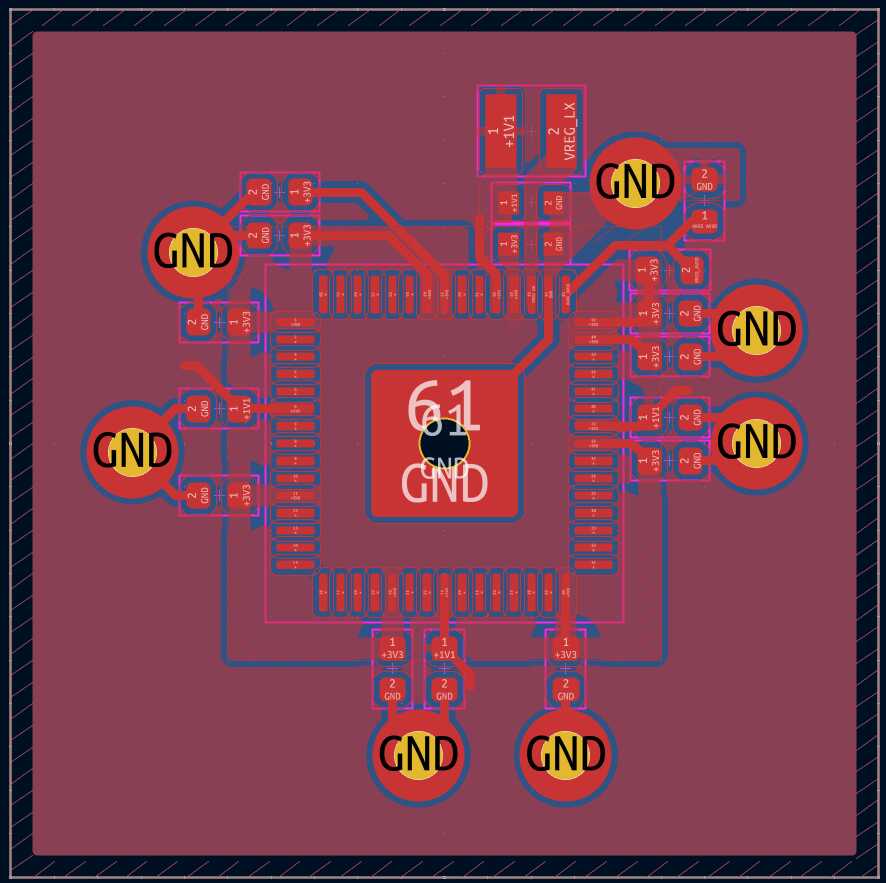

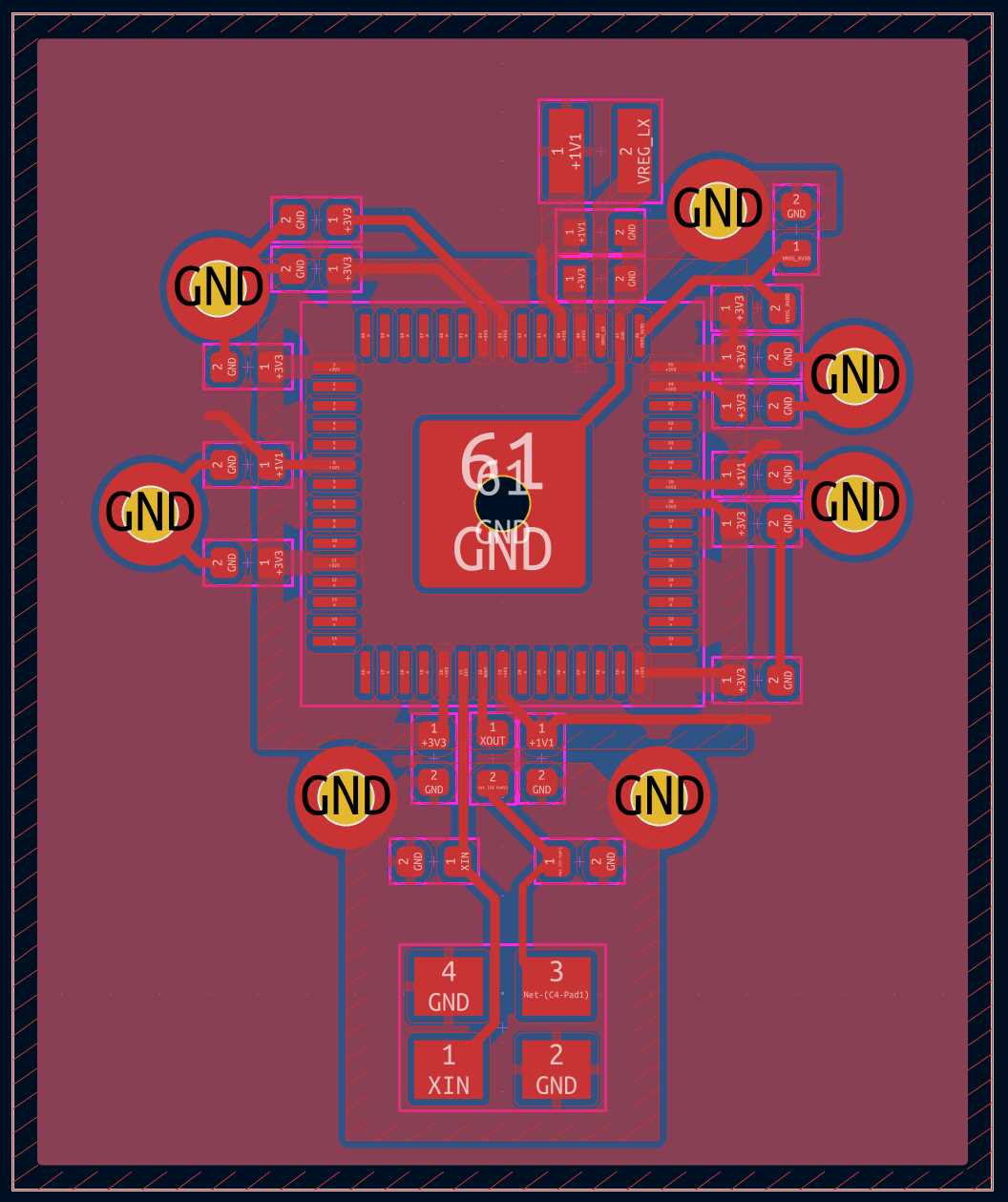

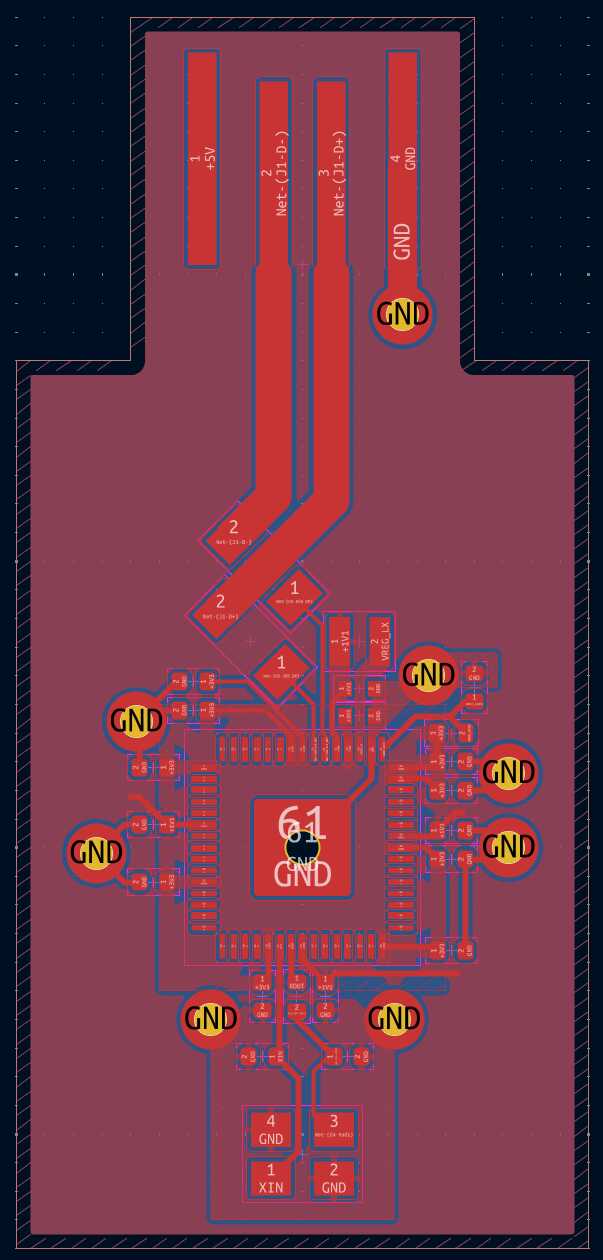

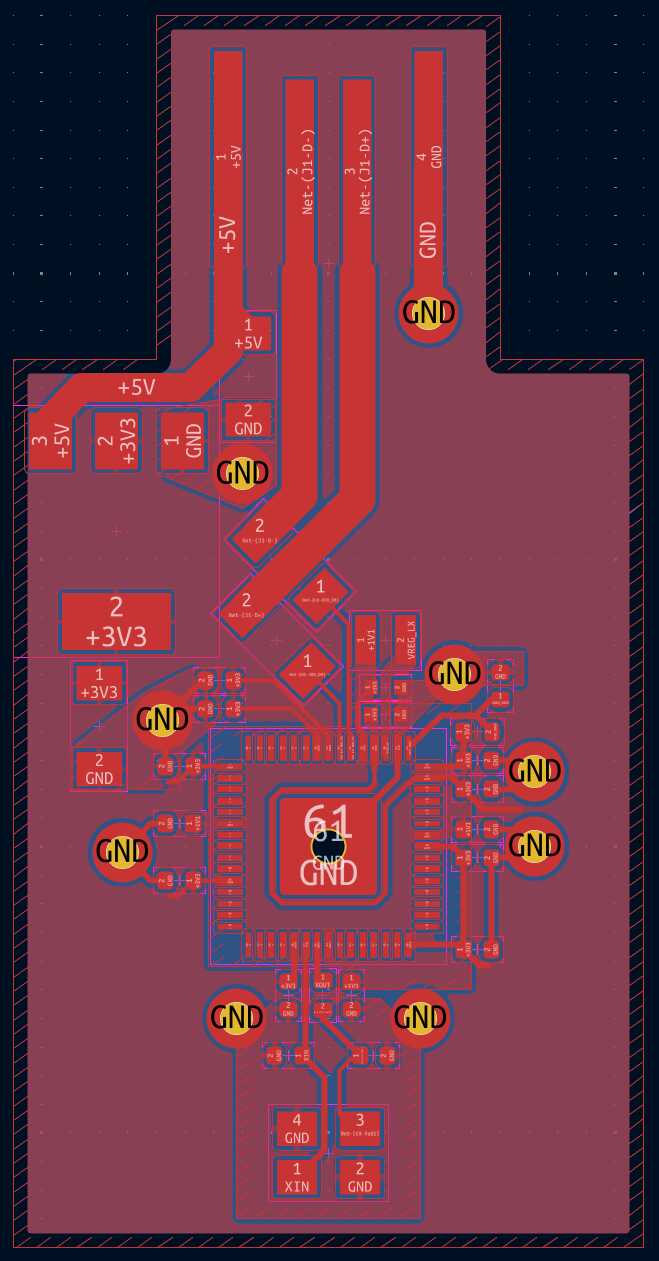

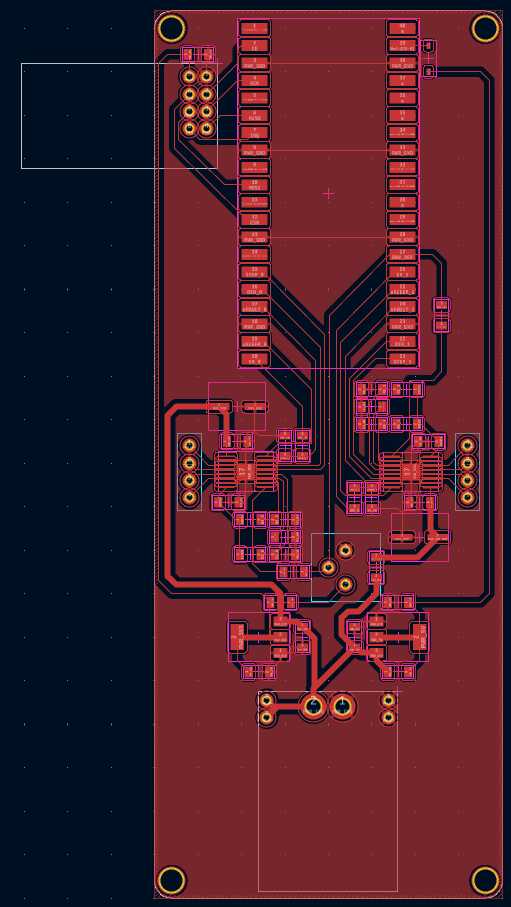

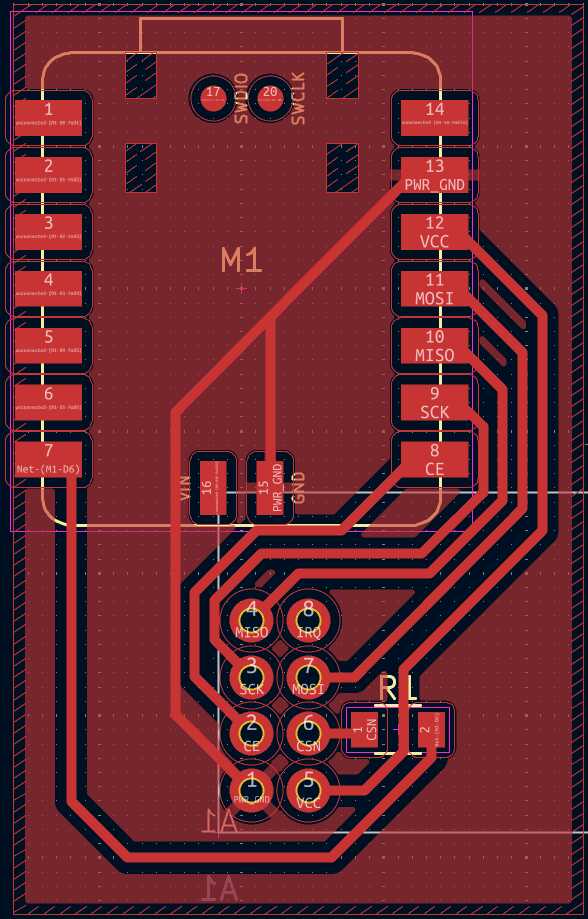

[12/4-12/8] Designing dongle_medium

I then designed

my own board.

I started with the “dongle” board, that will connect to my computer.

It includes the RP2354A and a header for

an nRF24L01+ breakout board.

I called it dongle_medium.

I hope to make a dongle_small which does away with the breakout board,

but I know that the RF layout can take time, and I want to be conscious of all the work I have left.

I can also create a dongle_large with a XIAO if I run into problems with milling or soldering dongle_medium.

I started by copying the RP2354A footprint and symbol from the reference board. The only ground connection on the package in the thermal pad, and the footprint includes 9 vias to a ground plane on the other side of the board. The ground plane is a good idea, and is doable with 2-sided FR1 stock. However, the tiny vias are not doable. I replaced them with a single 1.1mm hole, which I know from machine week fits a M0.9X2.5 rivet nicely. I plan to insert this rivet from the back side, so that the flatter end ends up under the chip. Hopefully that doesn’t lift it off the board too much.

Then, I focused on the switching regulator components.

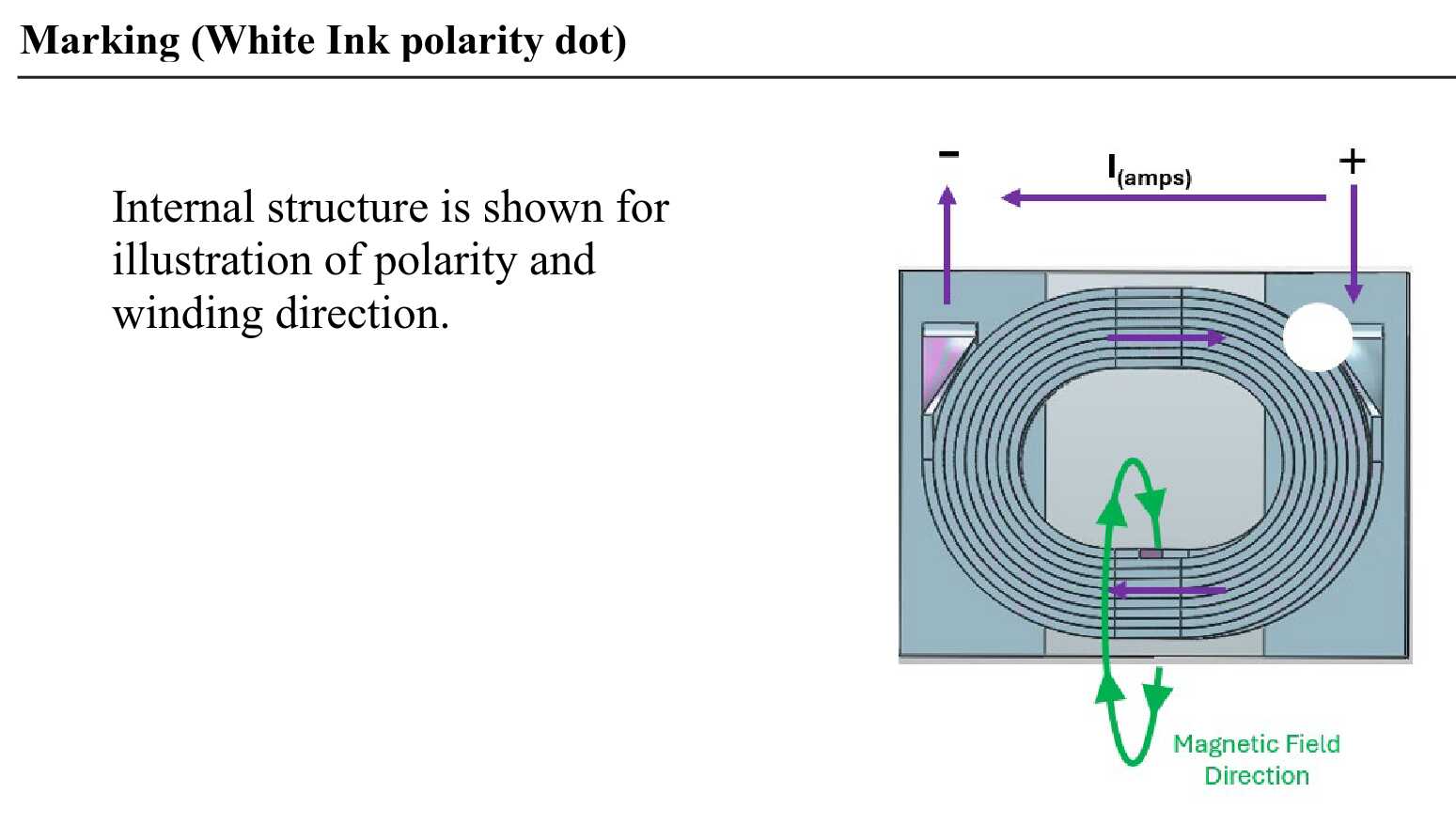

The hardware guide is very emphatic about using a particular “polarized” inductor

(AOTA-B201610S3R3-101-T, which they co-designed with Abracon) and the PCB layout that they came up with.

They claim:

It turns out that the magnetic field emitting from a ‘wrong way round’ inductor interferes with the regulator output capacitor (C7), which in turn upsets the control circuitry within RP2350.

The datasheet for the inductor clarifies what they mean by “wrong way round”:

I still don’t fully understand what the exact failure mode is inside the ceramic C7, but I figured there is no reason to deviate more than necessary.

I started with their circuit and layout (Figure 16), and modified it to fit our flow. Namely, I had to remove the small vias, and insert our large 1.1mm vias, which in turn required moving the low-pass filter on the feedback pin. I can’t imagine that’s a problem.

Next, I inserted decoupling capacitors. I used the same 0402 package that they did, and I added two that they had omitted because I have more space than they did. Routing 3v3 and 1v1 is tricky, because both appear on each of the four sides. I don’t want to rely too much on the back side though, because registration with the laser might be tricky. So, I decided to leave the backside as ground only, I routed 3v3 around the ground pad inside the chip, and I routed 1v1 all the way around the chip and caps. I relied on the backside for all ground routing, except for the routing that came with the switching regulator component layout. My result is shown in Figure 17.

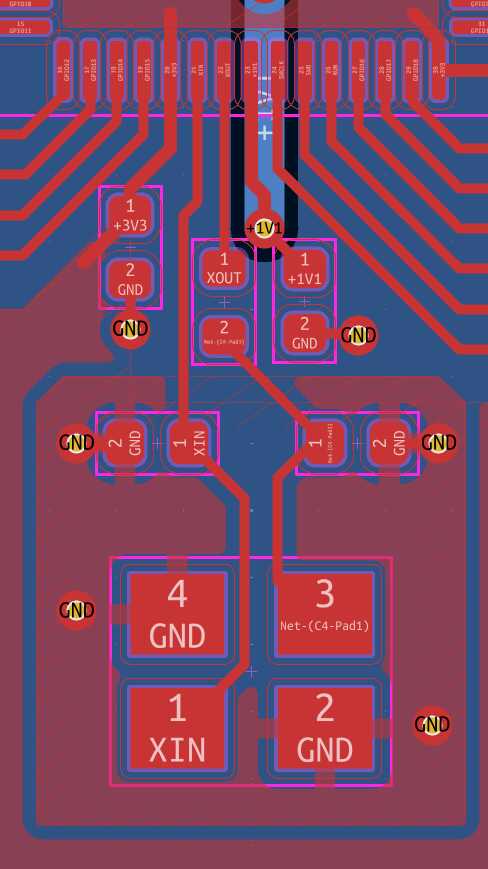

I skipped Flash, because the internal 2 MiB will be plenty, and tackled the crystal next.

I thought about omitting it, but I plan to use USB, and I don’t know anything about the internal oscillator.

I again used the recommended crystal, ABM8-272-T3, and started with their layout:

I moved things around to fit. Note that the 1v1 now routes all the way around the crystal unfortunately (the route in the north will be cut by the USB traces soon.

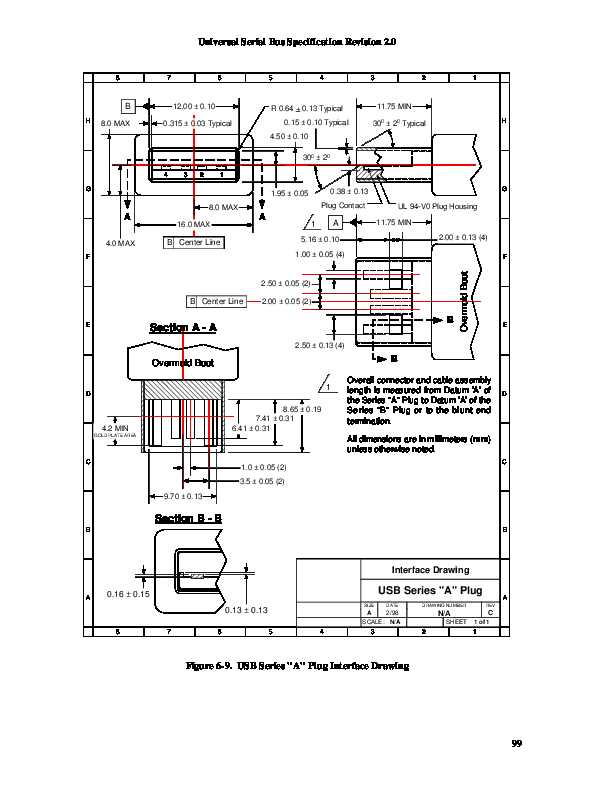

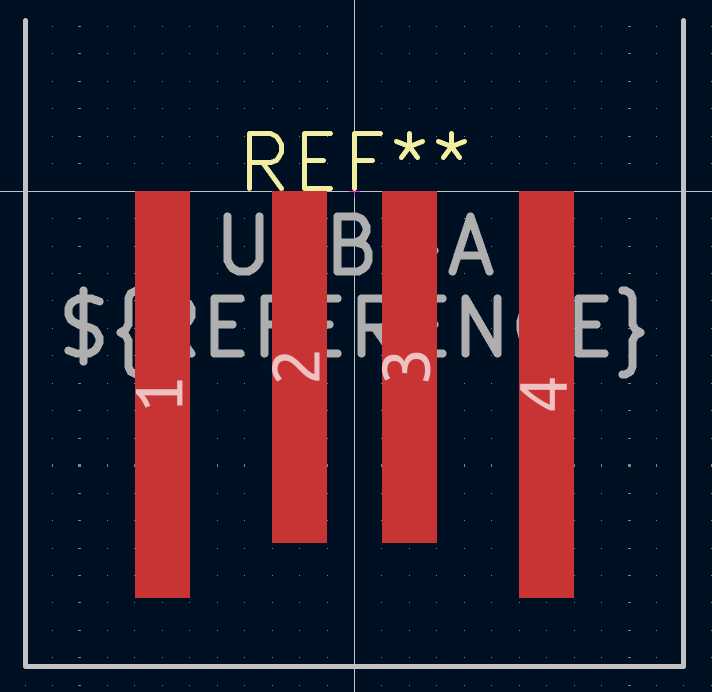

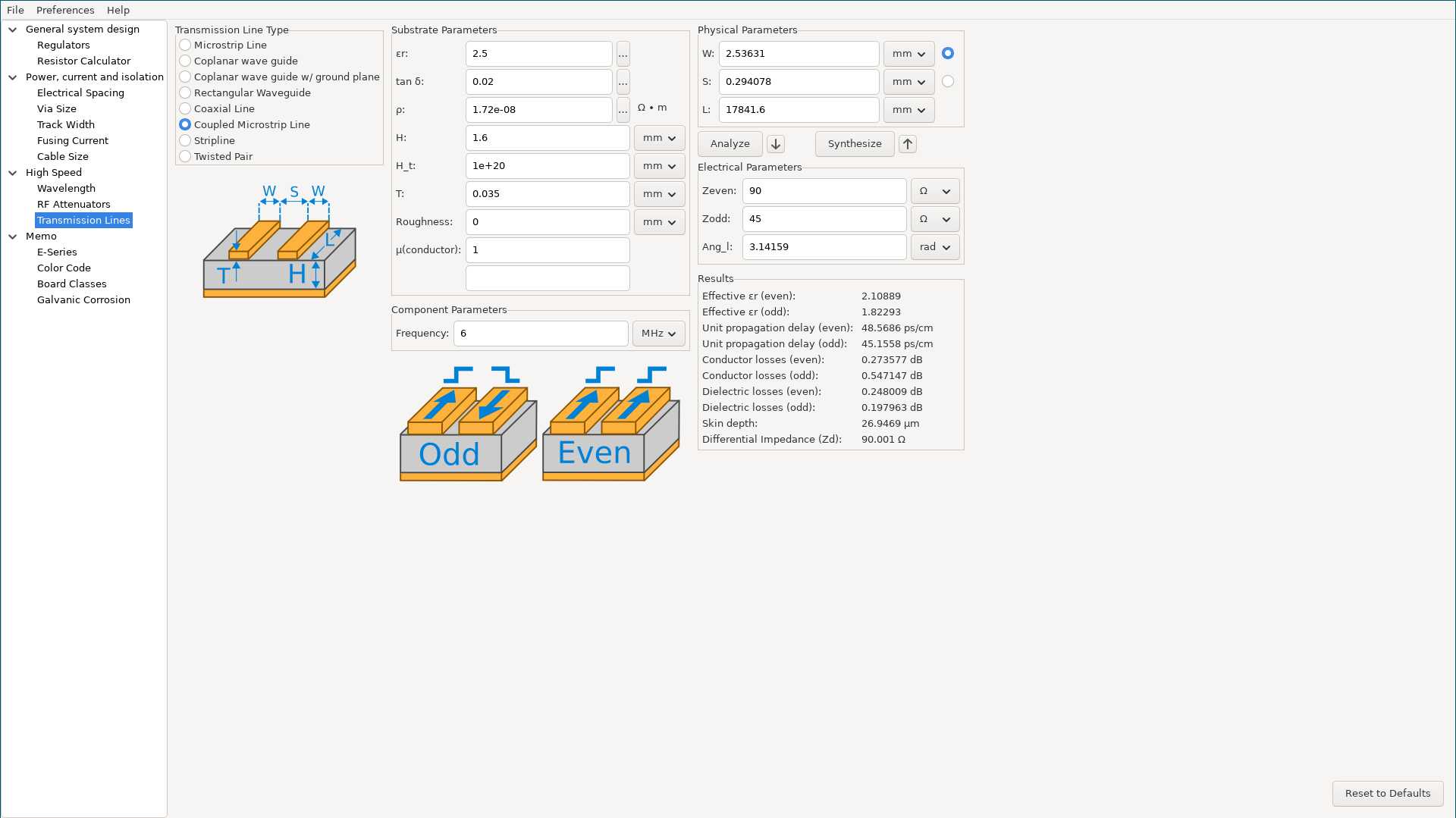

Next is USB. It didn’t occur to me to check in the fab library, so I used Figure 6-9 in the USB 2.0 Specification (https://www.usb.org/document-library/usb-20-specification; rev. 20250603; reproduced in Figure 20) to come up with a connector footprint:

The D- and D+ pins on the chip are arranged to hook up to a B receptacle. Frustratingly, the order on the A plug is flipped (meaning that the A receptacle and B receptacle have the same order, which doesn’t really make sense to me from a specification perspective). Luckily, the hardware design guide calls out 27Ω termination resistors close to the chip, so I can use one of them as a crossover (breaking symmetry a little bit).

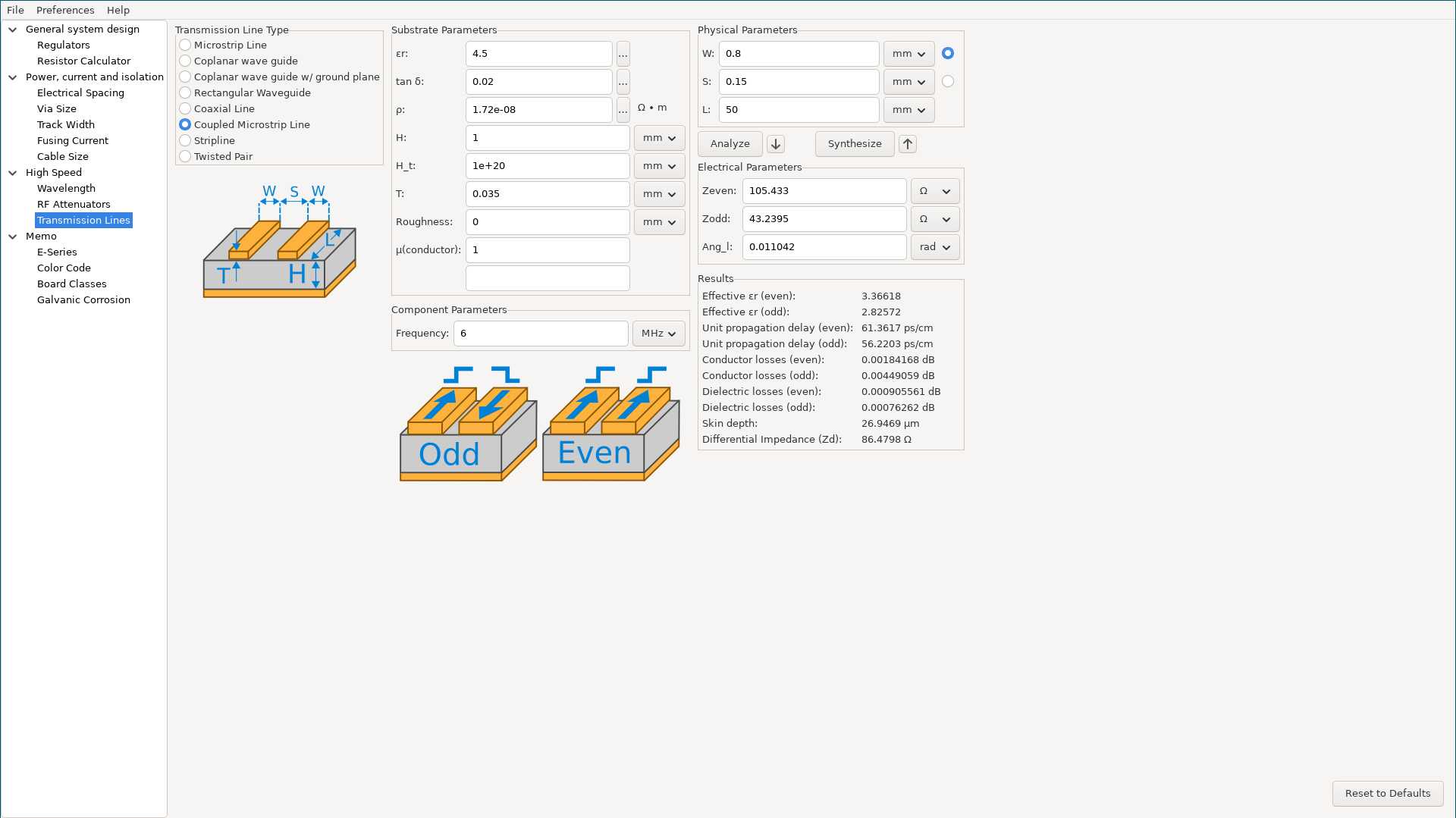

The differential impedance of the data lines should be 90Ω according to the spec. The hardware design guide claims to achieve this with 0.8mm traces spaced 0.15mm apart. The only information given about the board is that it has a height of 1mm. Using 6MHz as the target frequency (corresponding to 12Mbps, the FS data rate) and, more importantly, the dielectric constant for FR4, I see 105.4Ω in KiCAD:

So, I’m not totally confident that I am not missing something. But, this is close enough, so I used the KiCAD tool for our boards. I measured our stock to be approximately 1.6mm thick, which matches the documentation. I didn’t find anything on the copper thickness, so I’m assuming 1oz, or 0.35mm. Finally, I’m using a dielectric constant of 2.5 based on Quentin’s findings.

This gives a trace width of 2.54mm and a spacing of 0.29mm, which is impractical. Given the short run, and the inherent asymmetry from the crossover, I just made them as thick as possible:

Next, I had to add the input power supply.

I chose to use an LDO, like the example design did, but I chose one from the inventory (NCP1117).

When I went to lay it out, it occurred to me it makes more sense to flip the 3v3 and 1v1 pours,

so I worked through that as well:

Finally, I added the nRF24L01+ Breakout.

I used SPI1_RX, SPI1_SCK and SPI1_TX on GPIOs 8, 10 and 11, respectively, for routing convenience.

I also skipped the optional IRQ signal and used a different GPIO for CSn.

I put the board on the back, but couldn’t make it totally flush, because the planes have to route power around it.

The final result is shown below:

[12/5-12/7] DRV11873

My Week 9 experimentation with the A4949 was largely successful,

but it also taught me that the A4949 can only run motors in one direction.

I want the luggage to be able to move backwards and to turn in place,

so I had to find an alternative.

I picked the DRV11873 to try next.

According to the datasheet, reverse spinning is supported:

DRV11873 has an FR pin to set the motor for forward or reverse spin. During DRV11873 power up, FR status is set. During normal operation, the spin direction of the motor does not change if the FR status is changed. The FR status can be reset if the PWMIN is pulled low; if FS is high, PWM must be pulled low for 300 µs, and if FS is low, PWM must be low for 600 µs. After being pulled down for the appropriate time, the FR status resets upon the PWM rising edge. It requires resetting the PWM signal, but that should not be a problem.

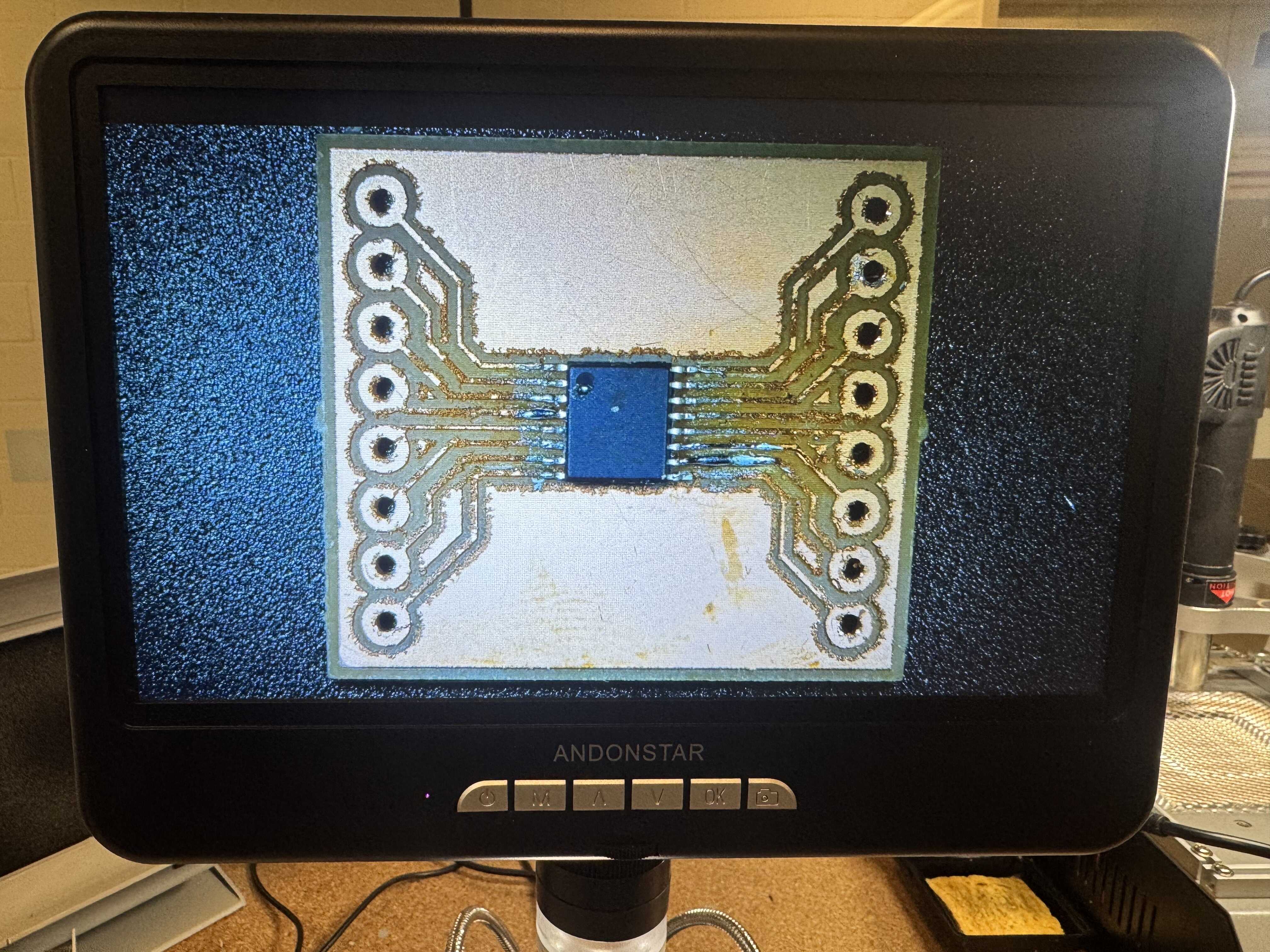

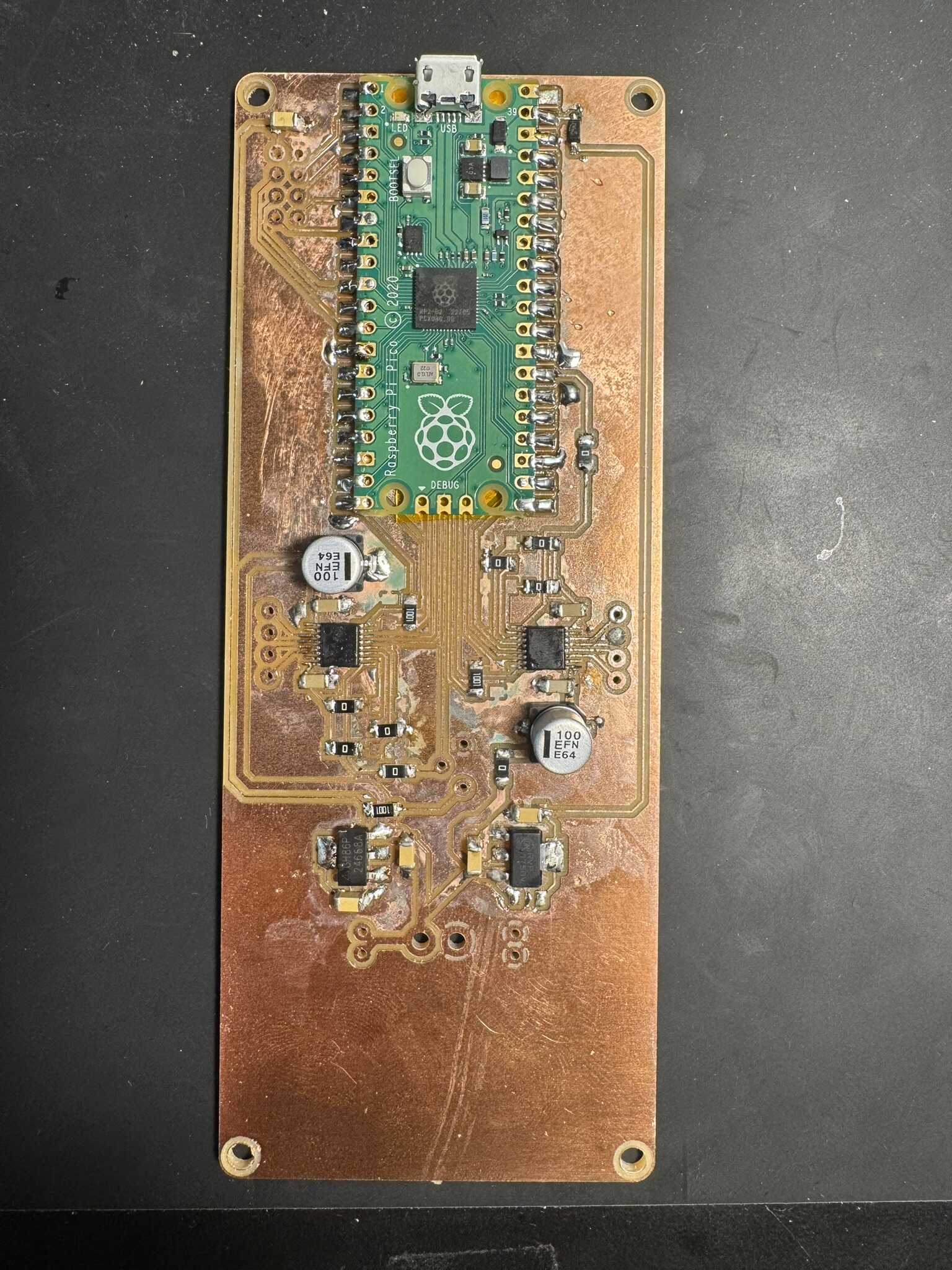

For prototyping, I made a breakout for the chip:

However, before I had a chance to test it, I discovered another problem:

The bore size of the BLDCs we stock is smaller than the bore size of the GT2 pulleys we stock. For this reason alone, I decided it’s better to pivot to a stepper motor. Besides, Jake told me that a stepper motor will give me more torque in this application.

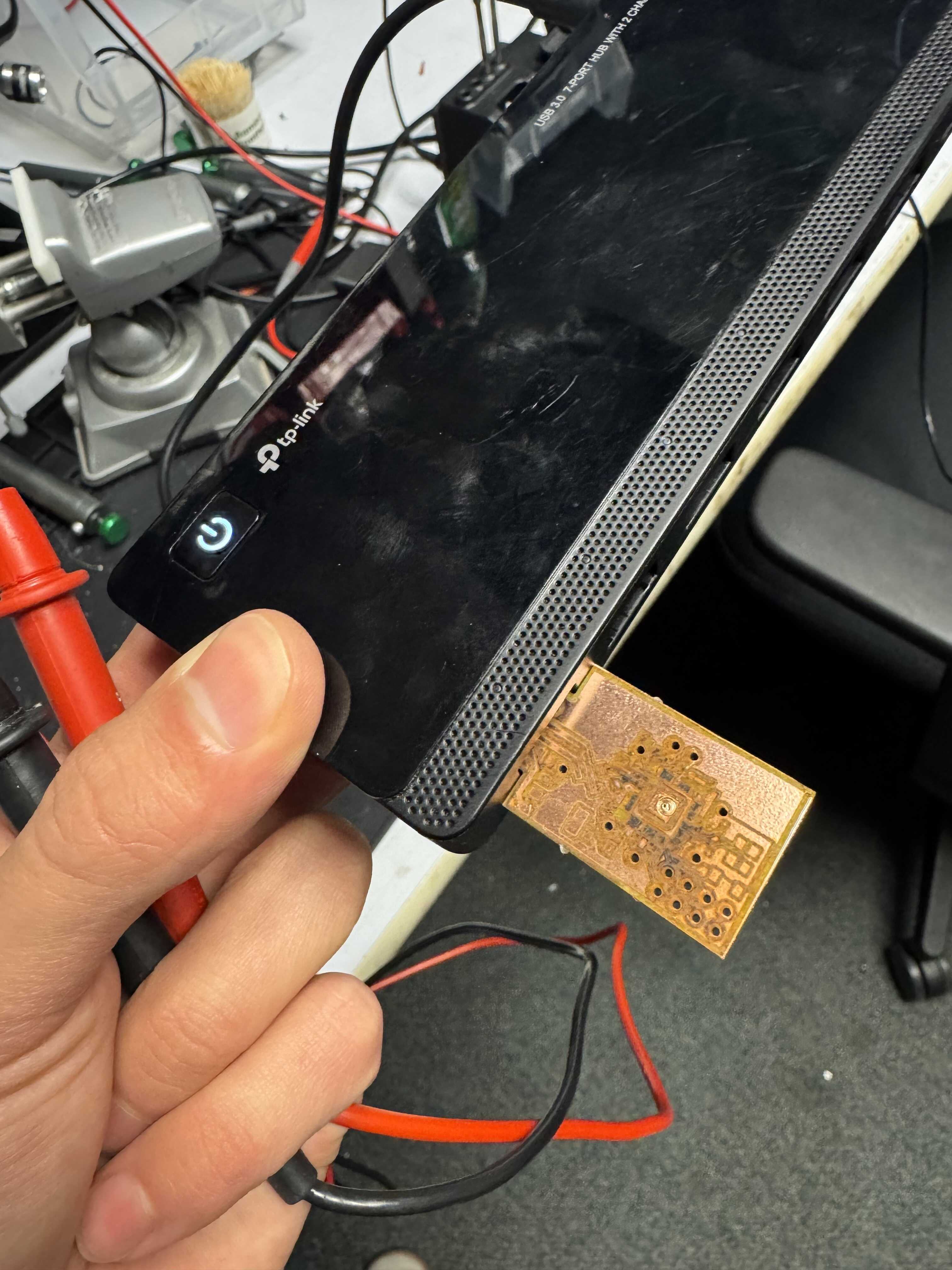

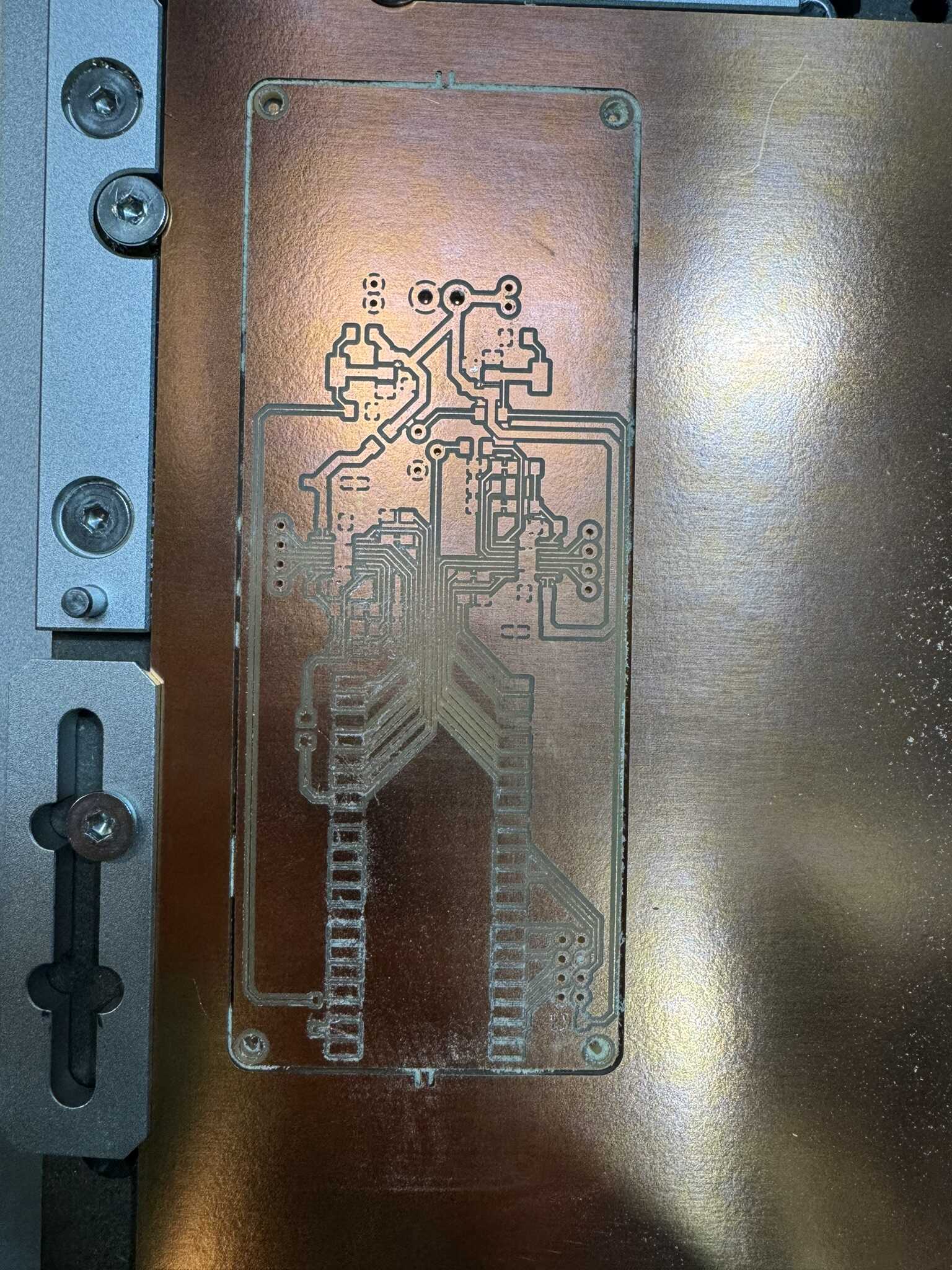

[12/8-12/9] Attempting to fabricate dongle_medium

I then went back to dongle_medium and attempted to fabricate it using the F2 Ultra.

My attempts are documented on my Week 14 page.

The good news was that the USB plug worked as expected (and supplied 5V):

Unfortunately, the laser engraving did not work so well, as discussed. I decided to abandon this approach for now in the interest of time. This leaves me with two possible paths forward:

- I can implement

dongle_largewith the RP2350 XIAO - I can keep a similar form-factor but use the tried and tested

ATSAMD21E18

I will think about which I prefer while I work on the mechanism a bit more.

[12/10] Figuring out the Mechanism

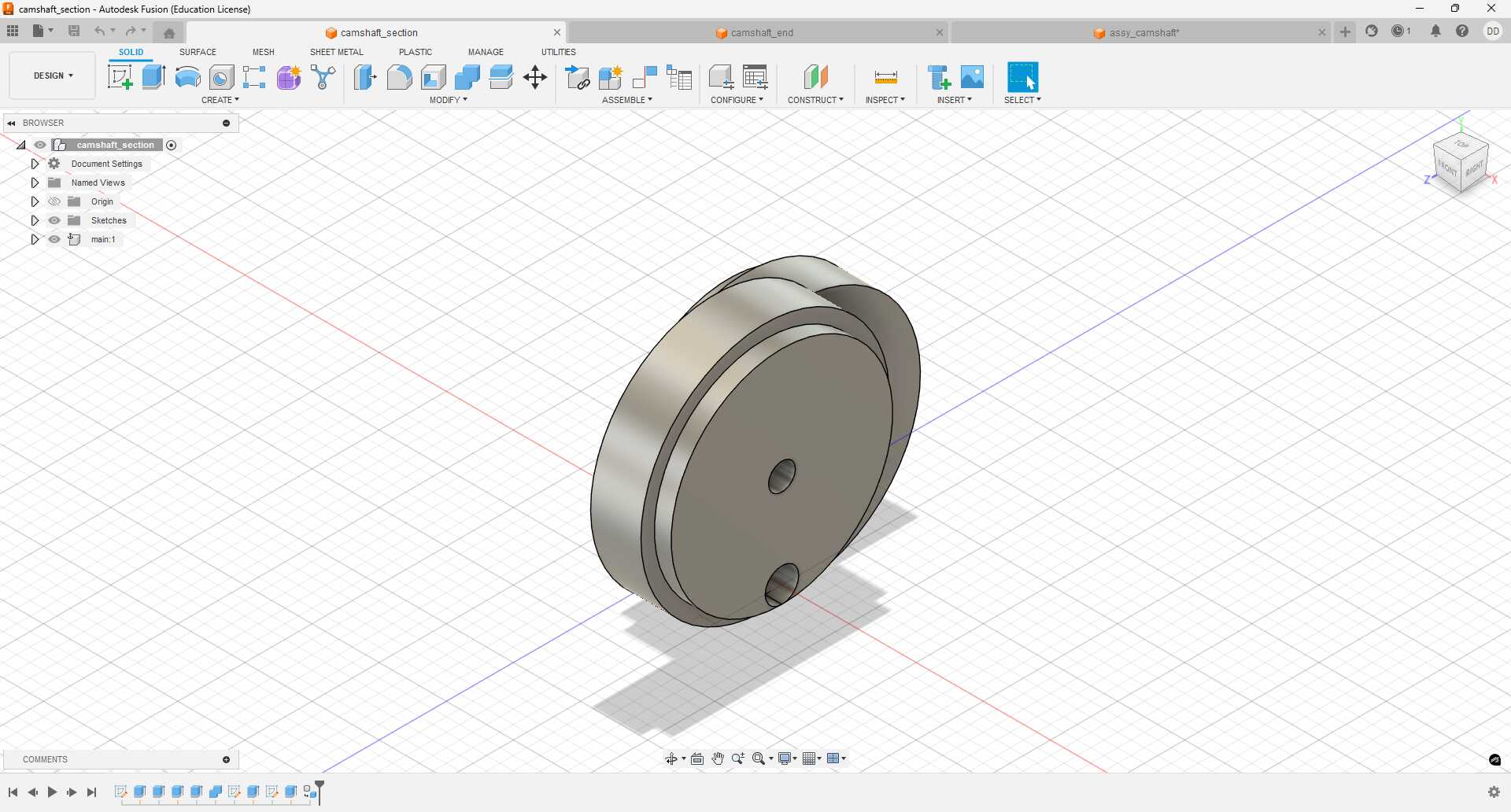

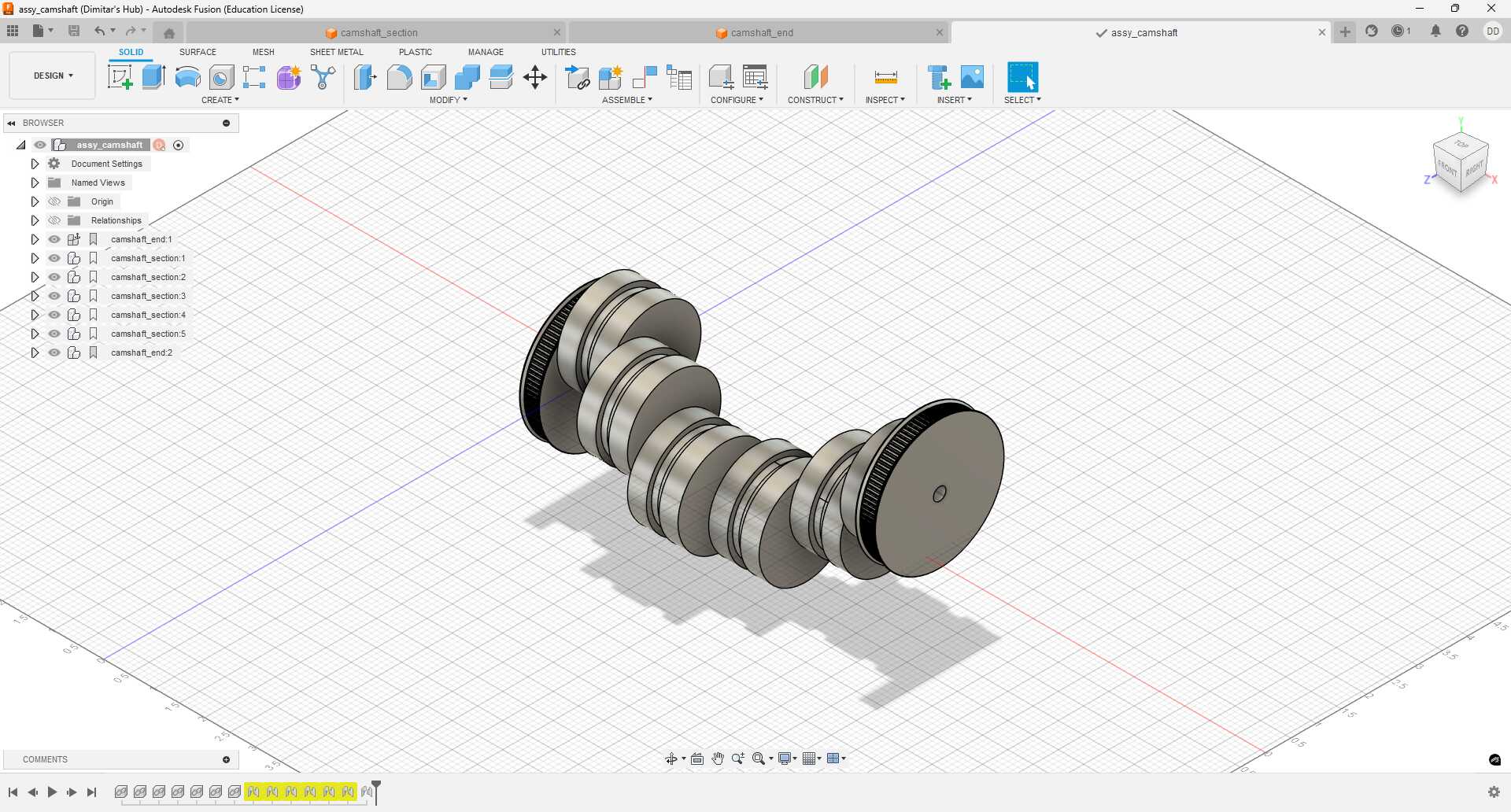

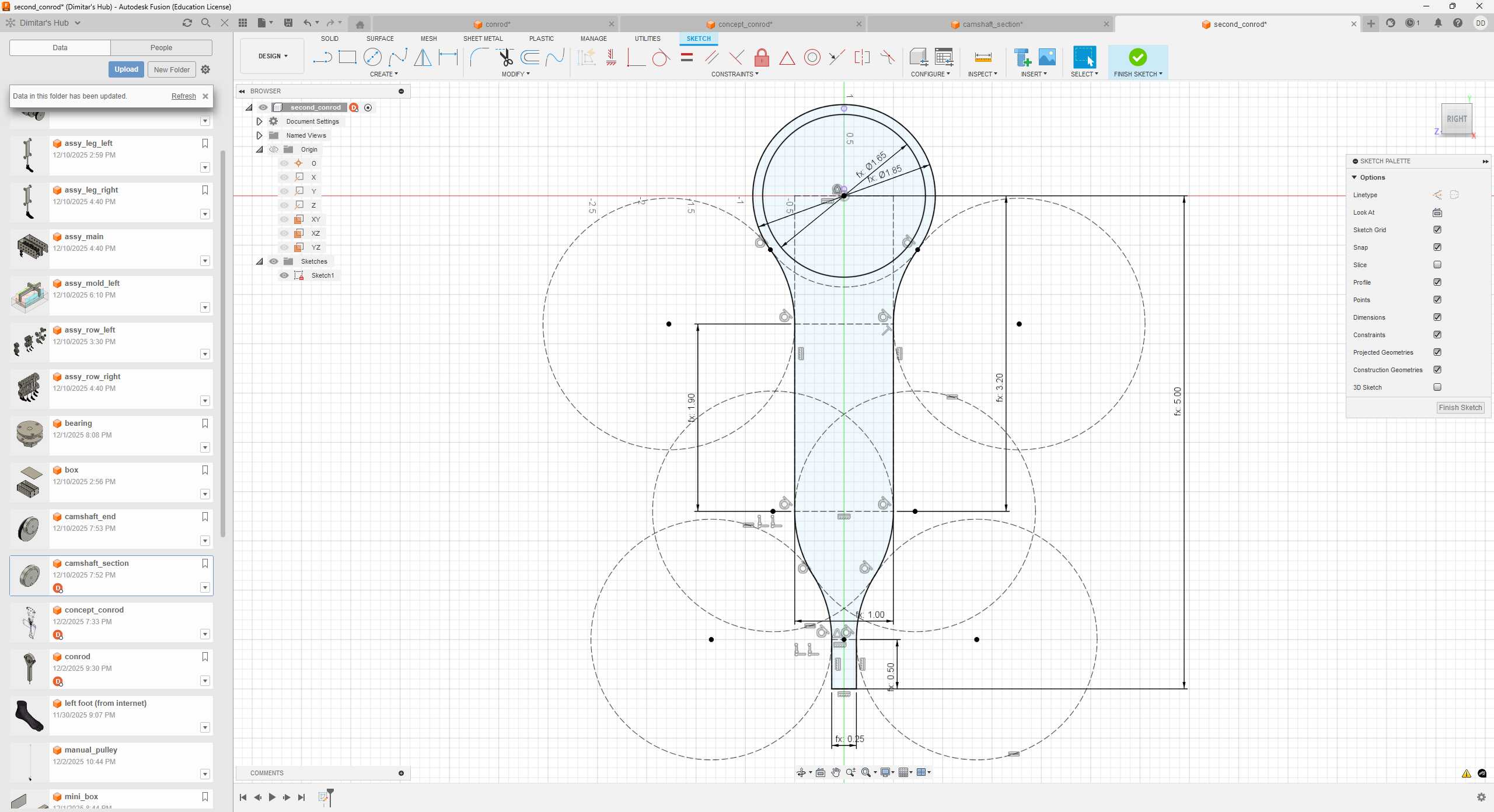

On Wednesday, I circled back to the mechanical components of my project (which carry the most risk because I have the least experience in this area). First, I talked to Dan, who helped me acquire wood for the outside of the box and cut it on the table saw to fit in the Thunder Laser. Then, I showed Jake my conrod design, and he gave me some great advice on how to improve it. So, I went back to the drawing board and started designing a third mechanism. This mechanism looks a lot more like a camshaft. It consists of five sections. Each two adjacent sections are held together by a conrod and a dowel. (Jake’s suggestion is to tighten the whole thing axially, but I’m still not totally clear on how to do that.)

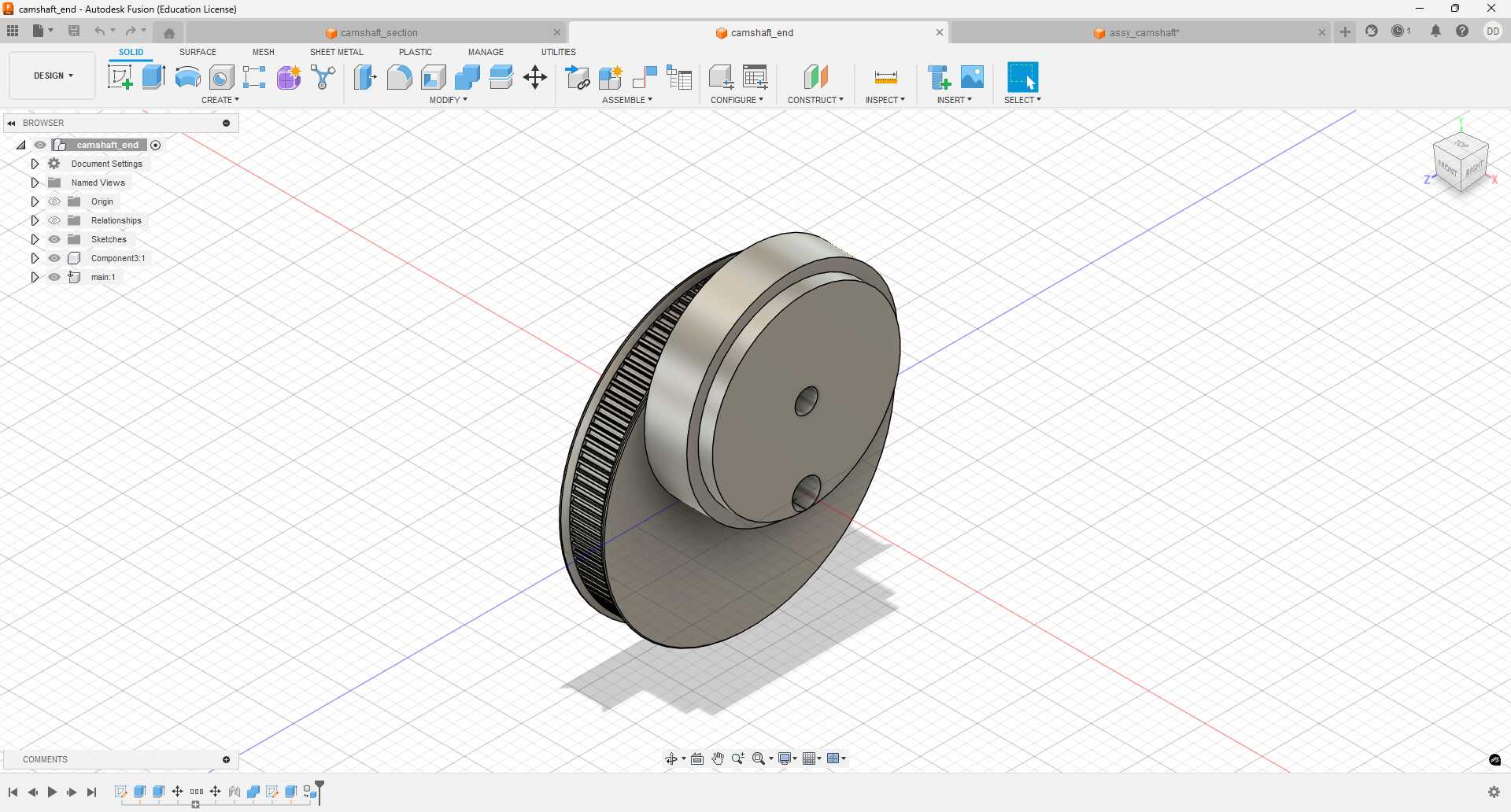

Five of the sections go between conrods (Figure 28). Two of the sections go on the ends, and include a GT2 gear, generated as described further above (Figure 29). Figure 30 shows how the whole camshaft comes together.

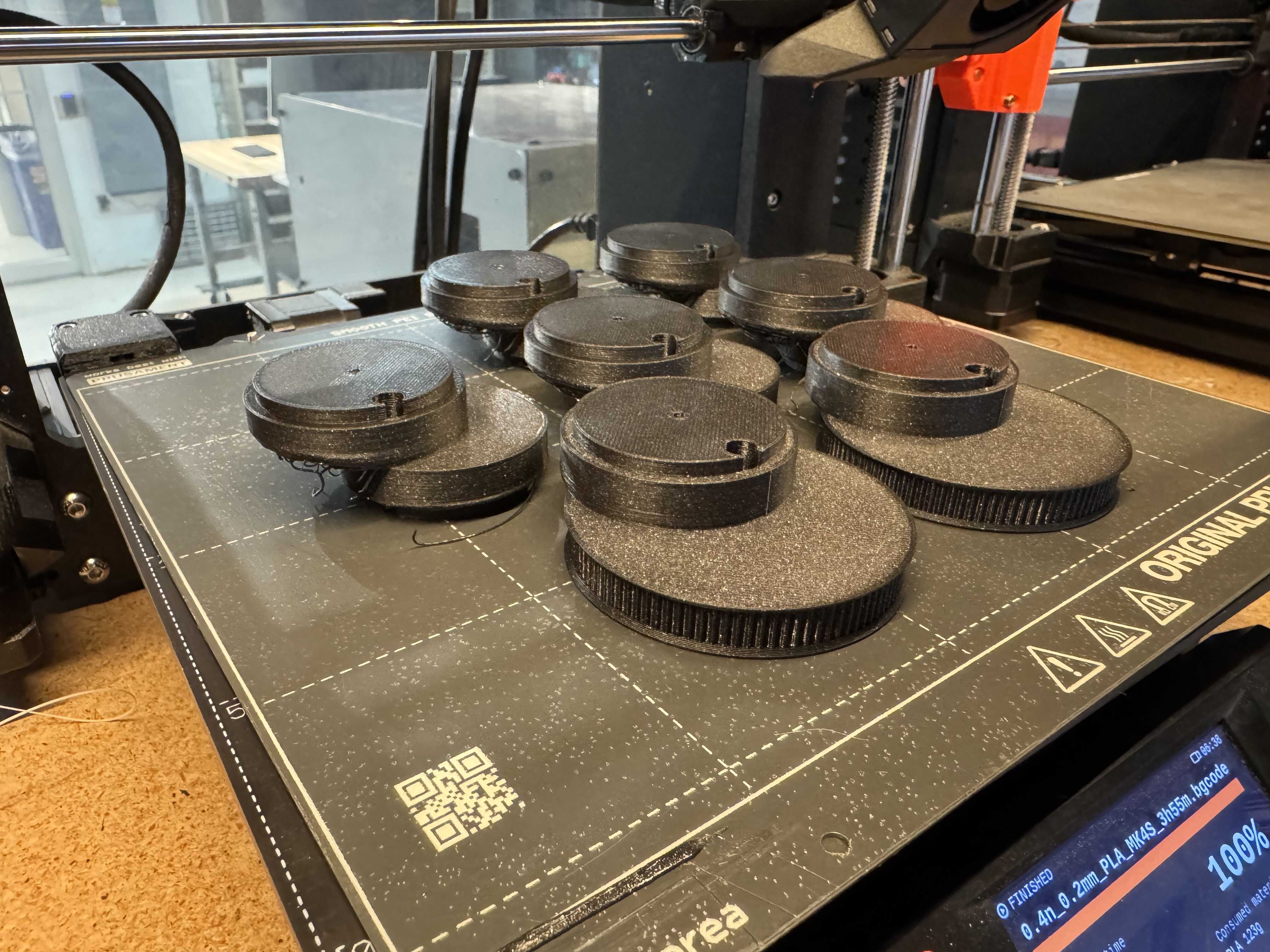

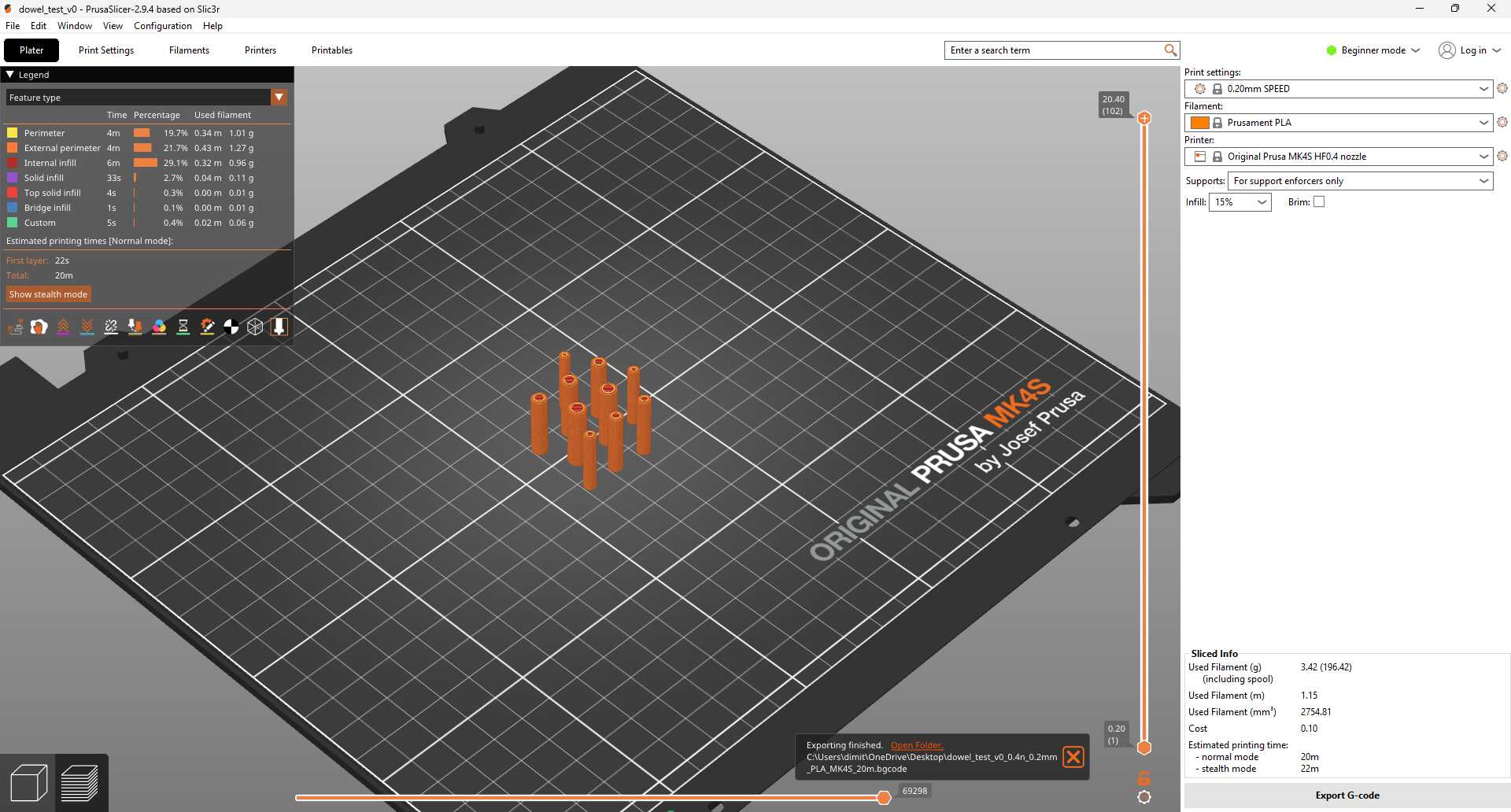

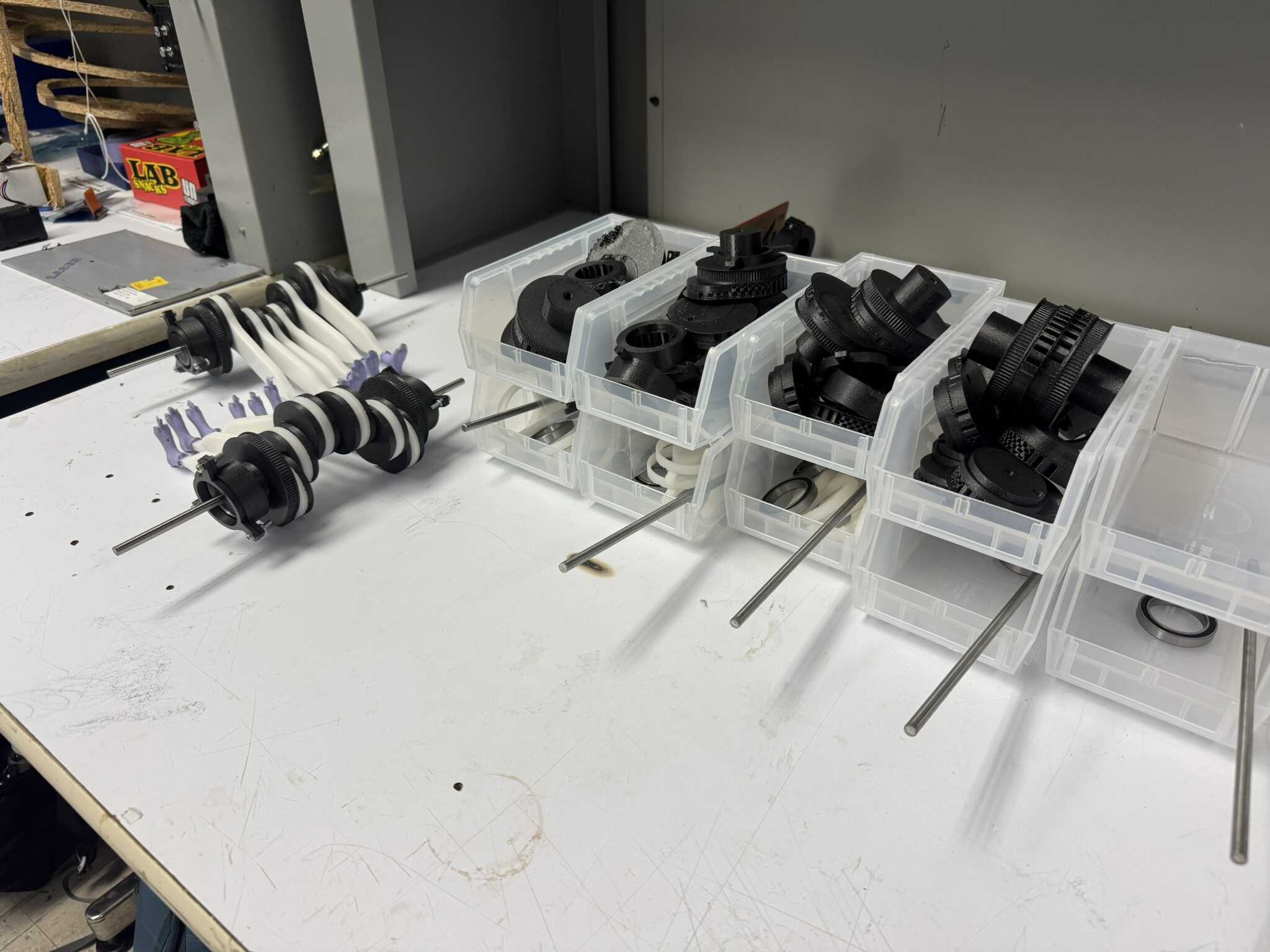

I 3D printed a set on the MK4S using Prusament PLA Galaxy Black.

I accidentally printed the wrong version (v0), so the dowel hole was 0.1in instead of 0.2in.

I kicked off a set of v1s, but let the first one finish so that I could start conrod testing as soon as possible.

The overhangs printed terribly, but luckily that surface is not important:

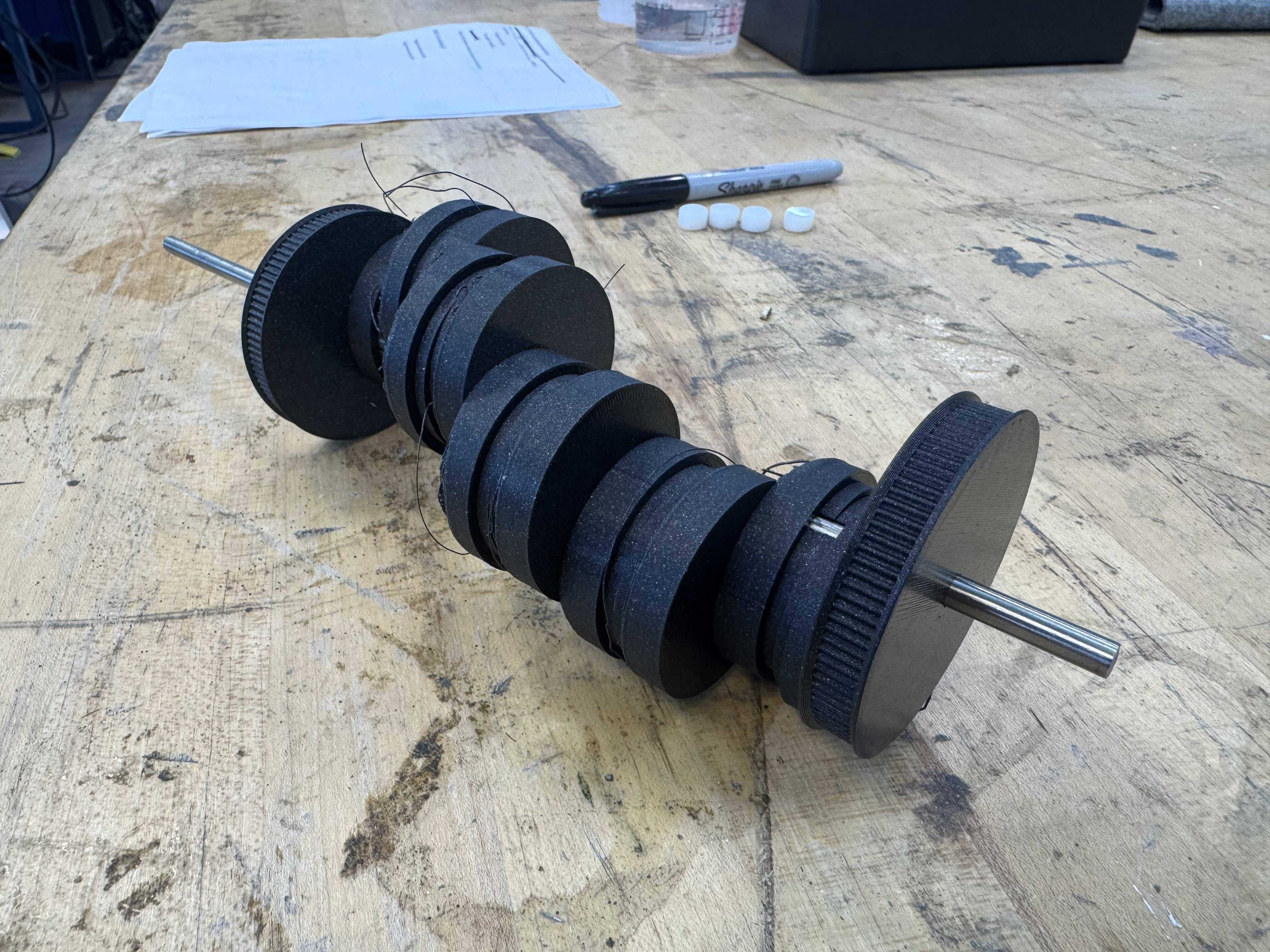

Here is the camshaft mounted on a 6mm rod:

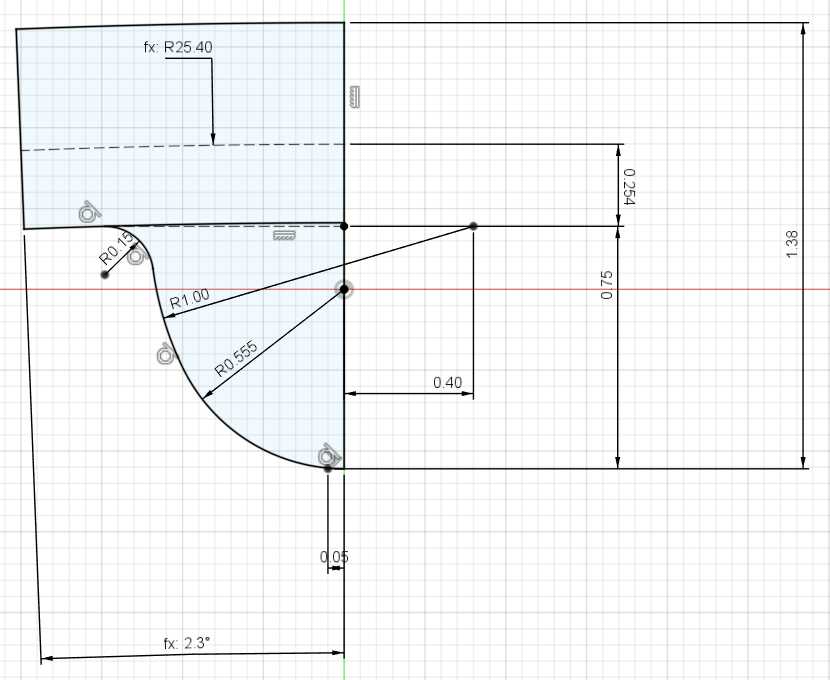

Next, I designed the new conrod:

A bonus of this approach is that we can safely increase the turning radius from 0.5in to 0.7in. This improves the geometry of motion nicely:

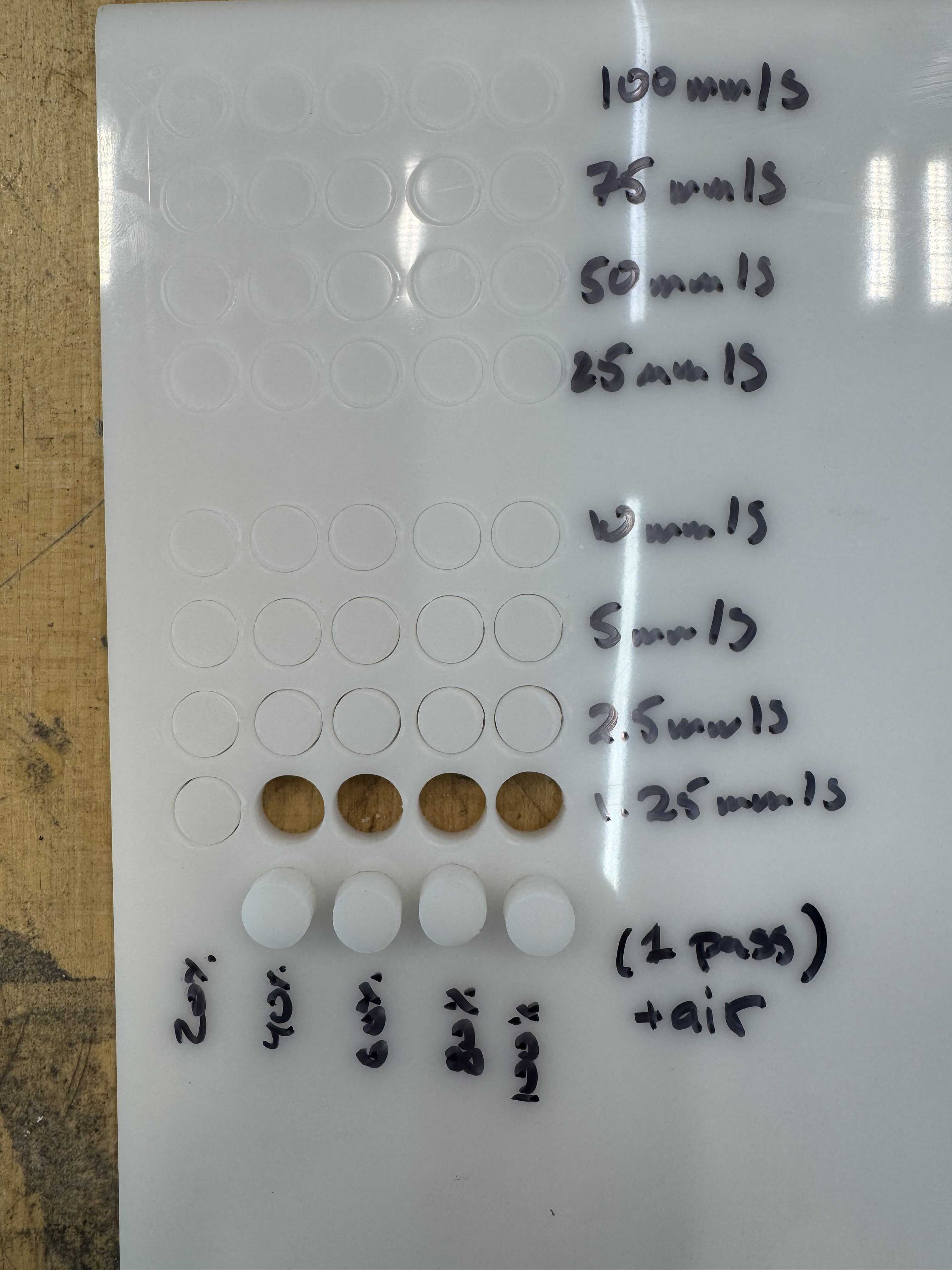

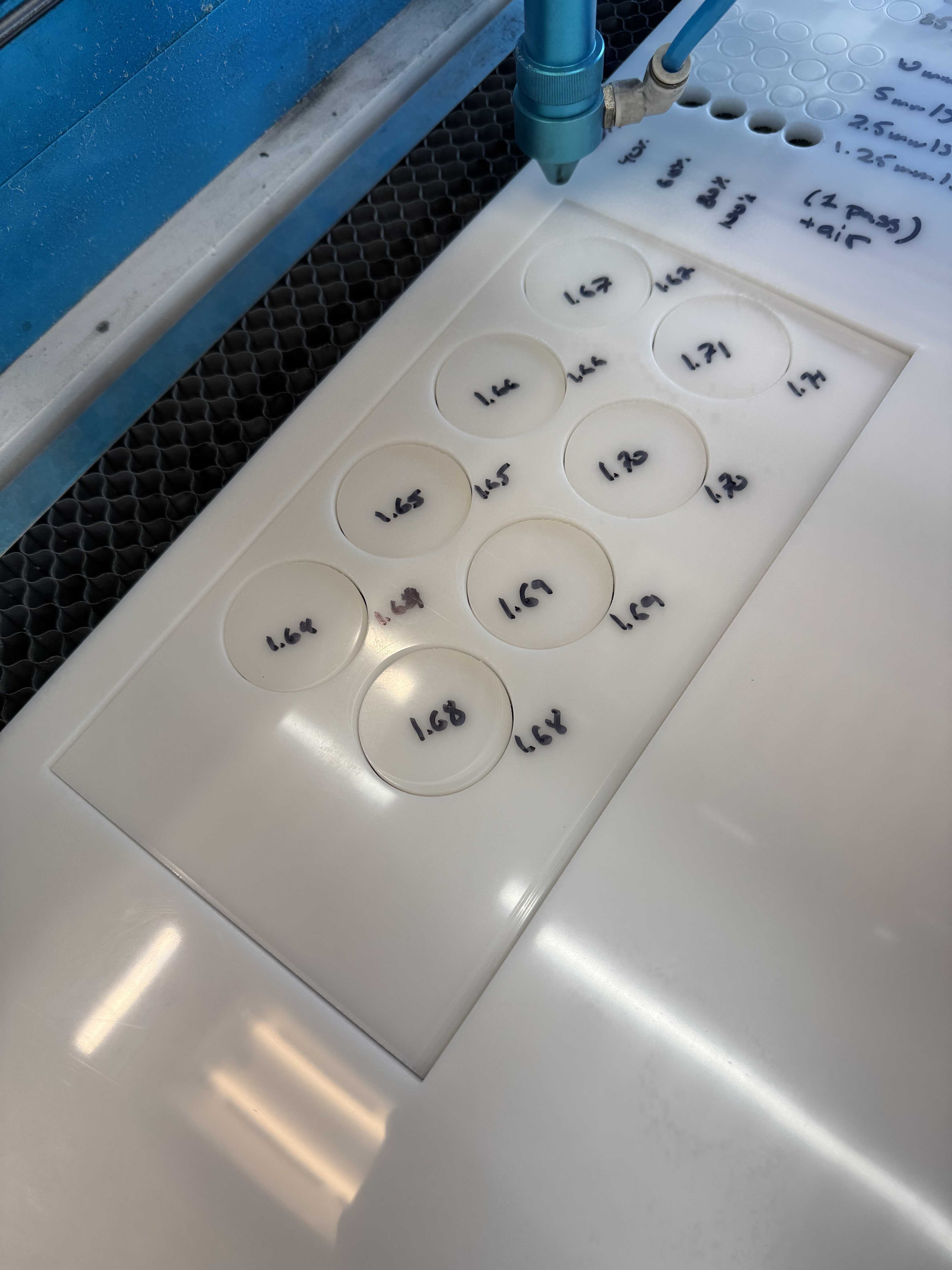

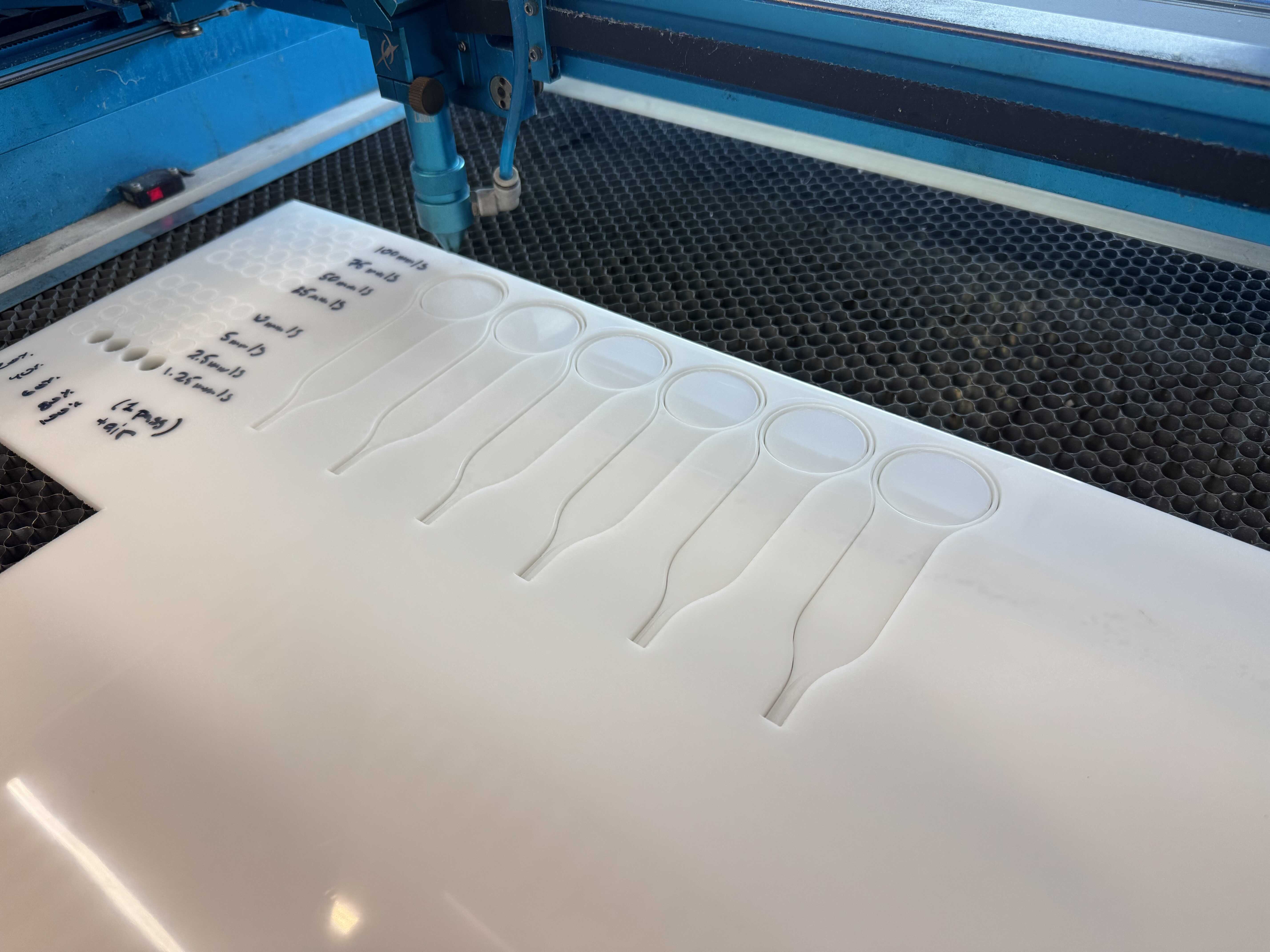

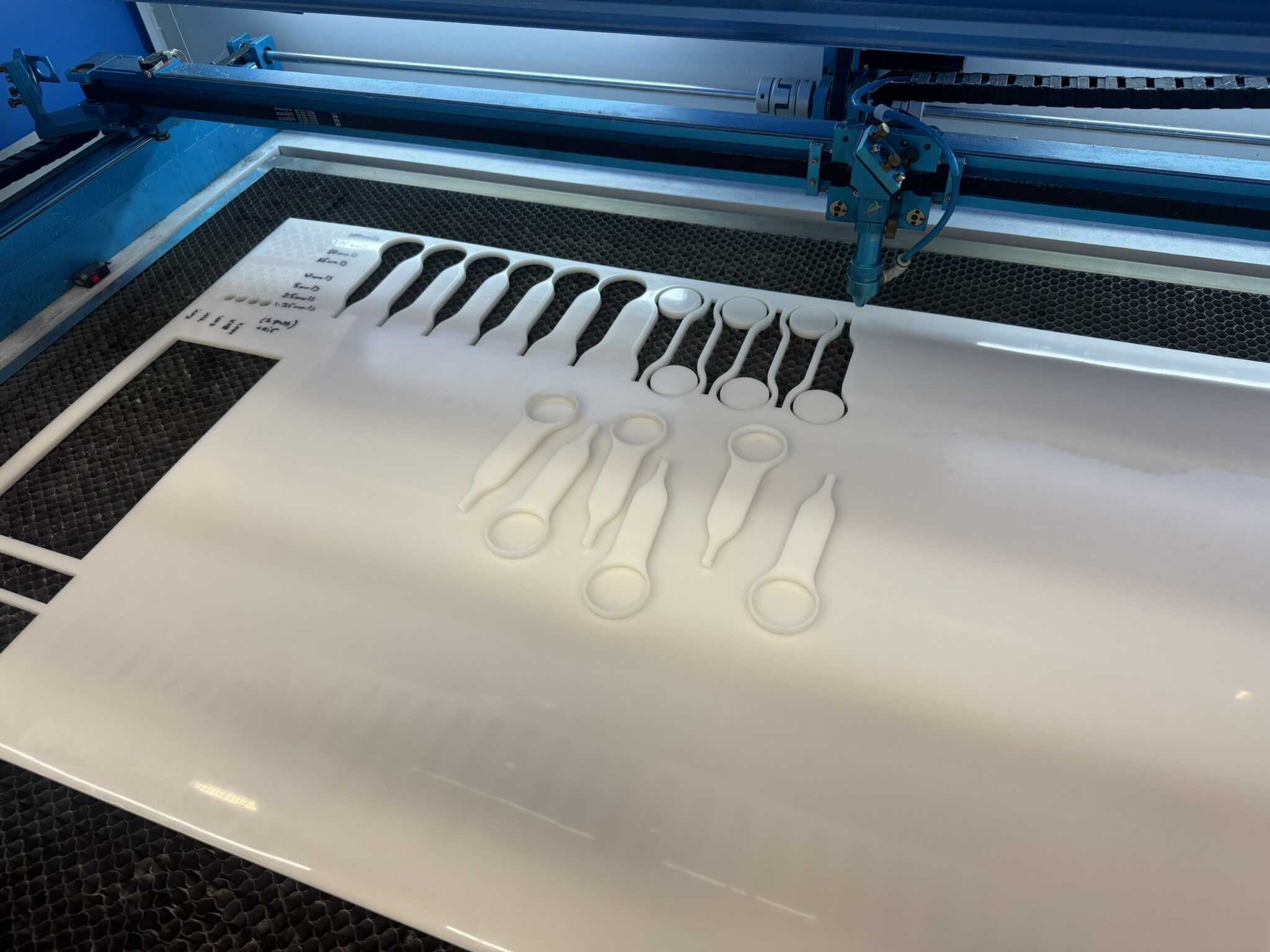

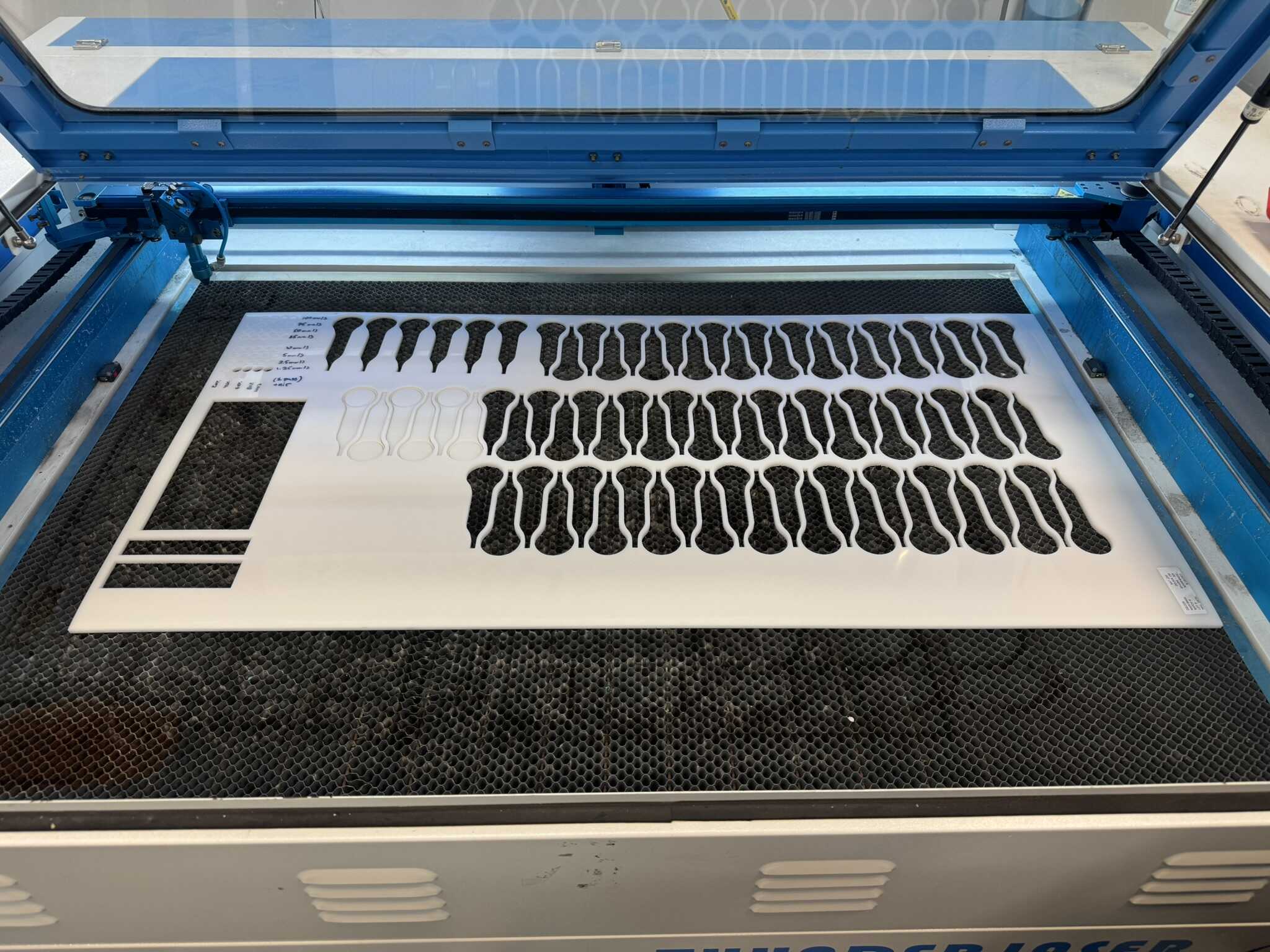

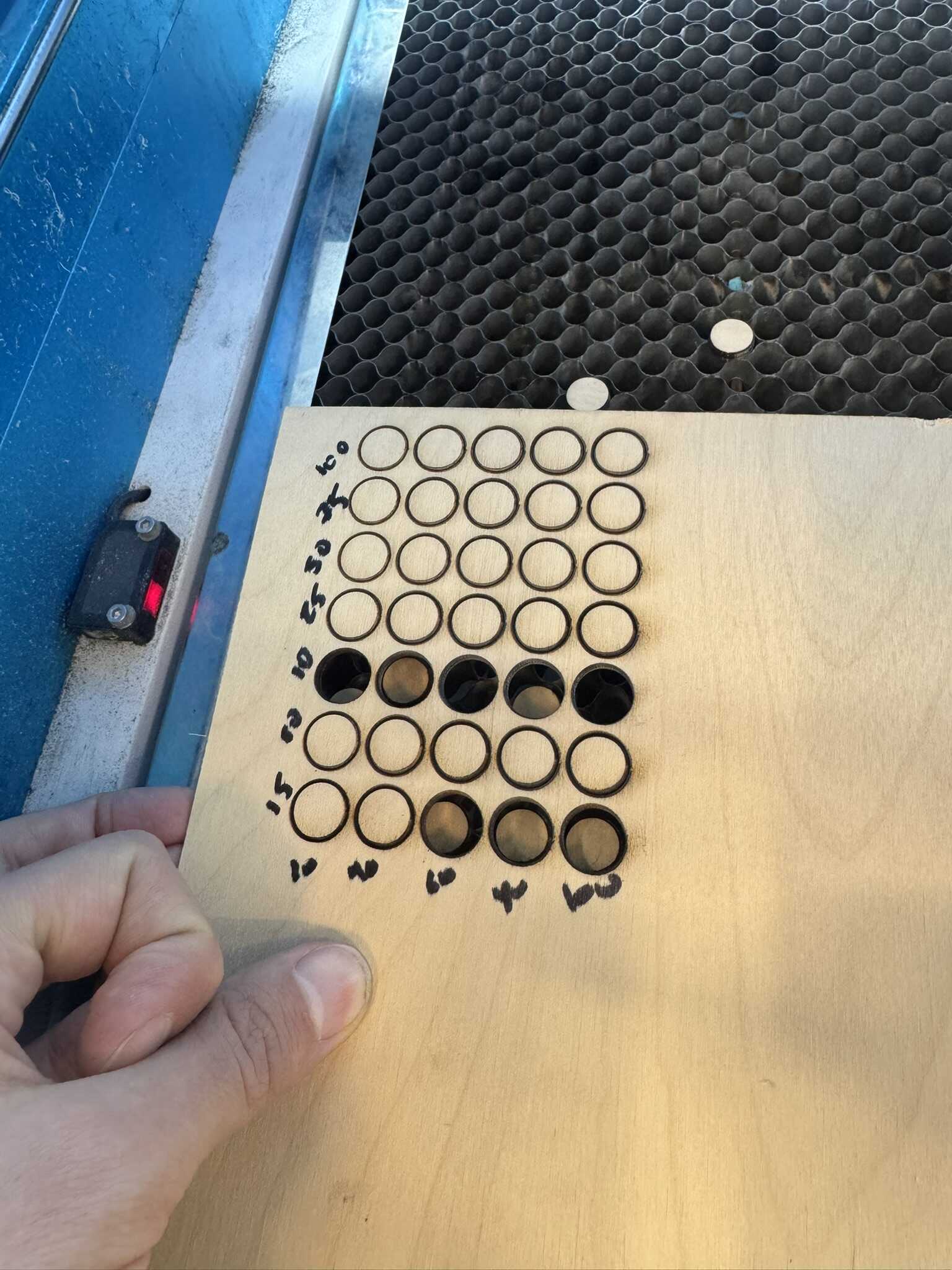

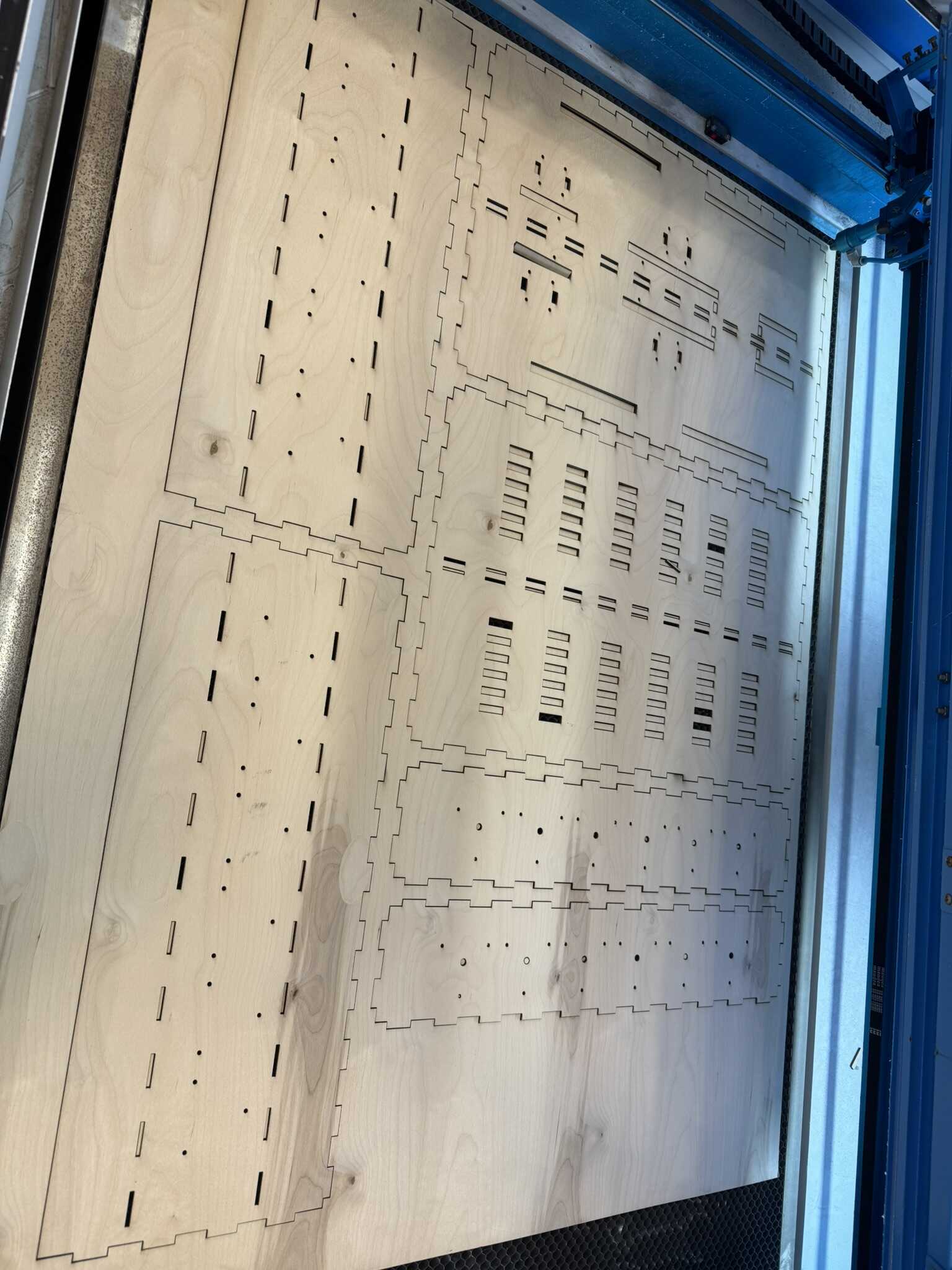

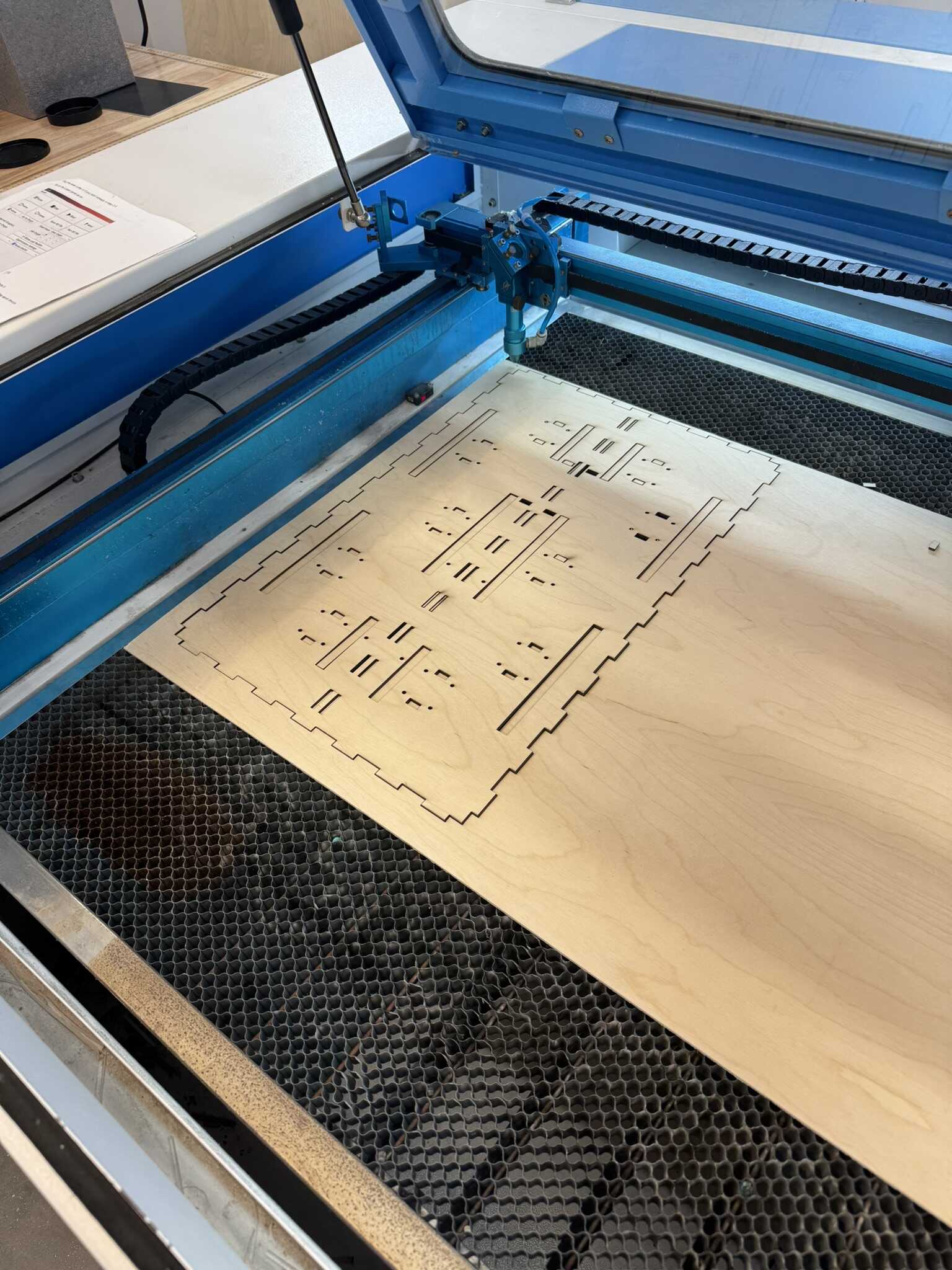

It would be prohibitively expensive to use bearings for the conrods, because there will be up to 72 of them. So, I decided to cut them out of Delrin instead. I acquired some 0.25in Delrin 150 and took it to the Thunder Laser. The first step was to figure out speed and power. I created a grid of 0.5in-diameter circles with powers in {20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%} and speeds in {100mm/s, 75mm/s, 50mm/s, 25mm/s}. None of them got even close to cutting through. So, I made a new grid with powers in {20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%} and speeds in {10mm/s, 5mm/s, 2.5mm/s, 1.25mm/s}. Only the 1.25mm/s with powers more than 20% cut through:

I settled on 1mm/s at 50%.

Next, I tested the inner diameter of the conrod. The corresponding diameter on the camshaft is nominally 1.65in. I cut out 8 circles of diameters between 1.64in and 1.71in (in increments of 0.1in).

It turns out I went in the wrong direction, as even the 1.64in fit happily:

This is because I didn’t account for the kerf of the laser when I chose where to start my array. The 1.65in fit well enough, so I kept it. The bigger issue was in the other dimension:

I can’t change the thickness of the Delrin, so this has to be solved in the 3D print. I was eager to test the mechanism, though, so I fabricated 6 conrods:

The back side of the cuts was a little rough, but it was really easy to sand it down. They fit the camshaft as expected from the previous test - that is to say, the fit was good in the diameter dimension, but tight in the lateral dimension. The good news was that the dowels seemed to be enough to hold the mechanism together!

I also figured out how large the pivot points have to be and fabricated a temporary bottom plate to test on:

When it came out of the laser cutter, I realized I had made two mistakes: I calculated the length using the wrong thickness (0.5in instead of 1in), and I didn’t test the cut width required for the 0.25in Delrin. I could fix the second problem with some light chiseling, but I decided to fabricate another version.

I fabricated a new plate and that worked better. I could see the expected motion! This one had a different issue though. The tolerance problem between the sections which was causing friction earlier was also causing a slight expansion of the camshaft, leading to an angle on the conrods. This meant the motion was jagged.

I went back to the CAD and fixed the issue, leaving a little tolerance on top (v2).

I also enabled supports this time, even though the slicer didn’t think they were necessary.

I started a new run (with one section too many, accidentally) and went home for the night.

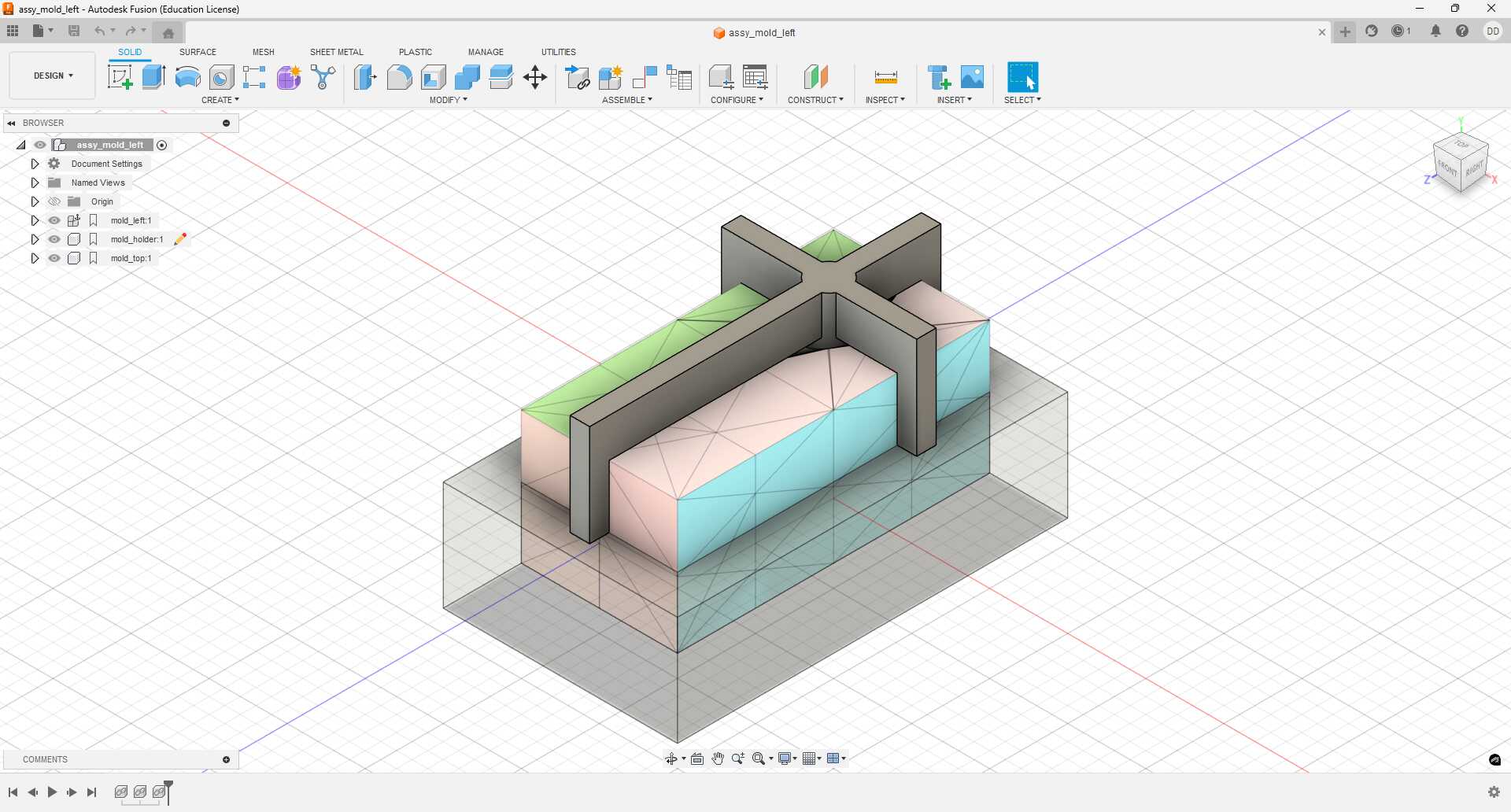

[12/10] Molding

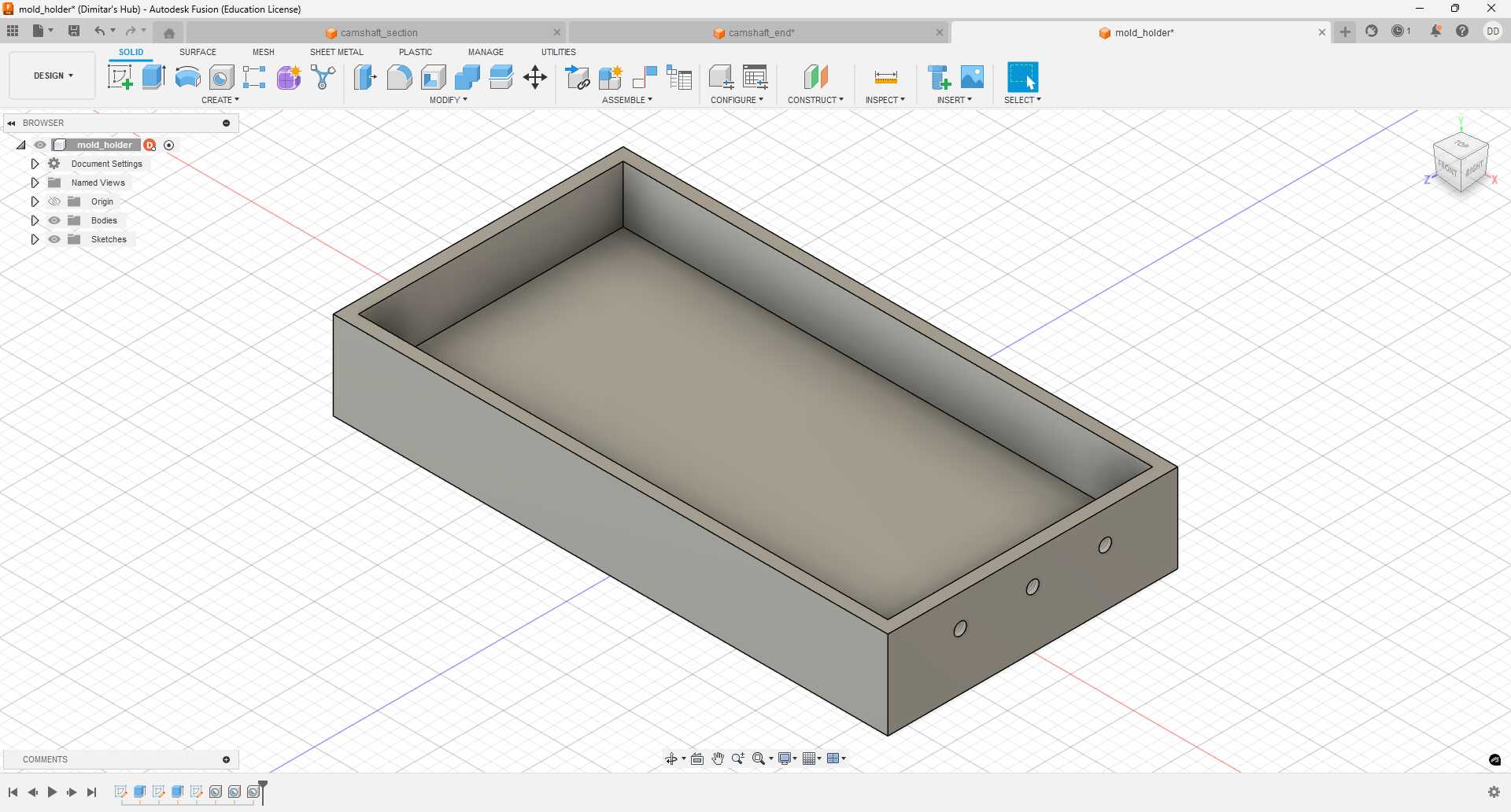

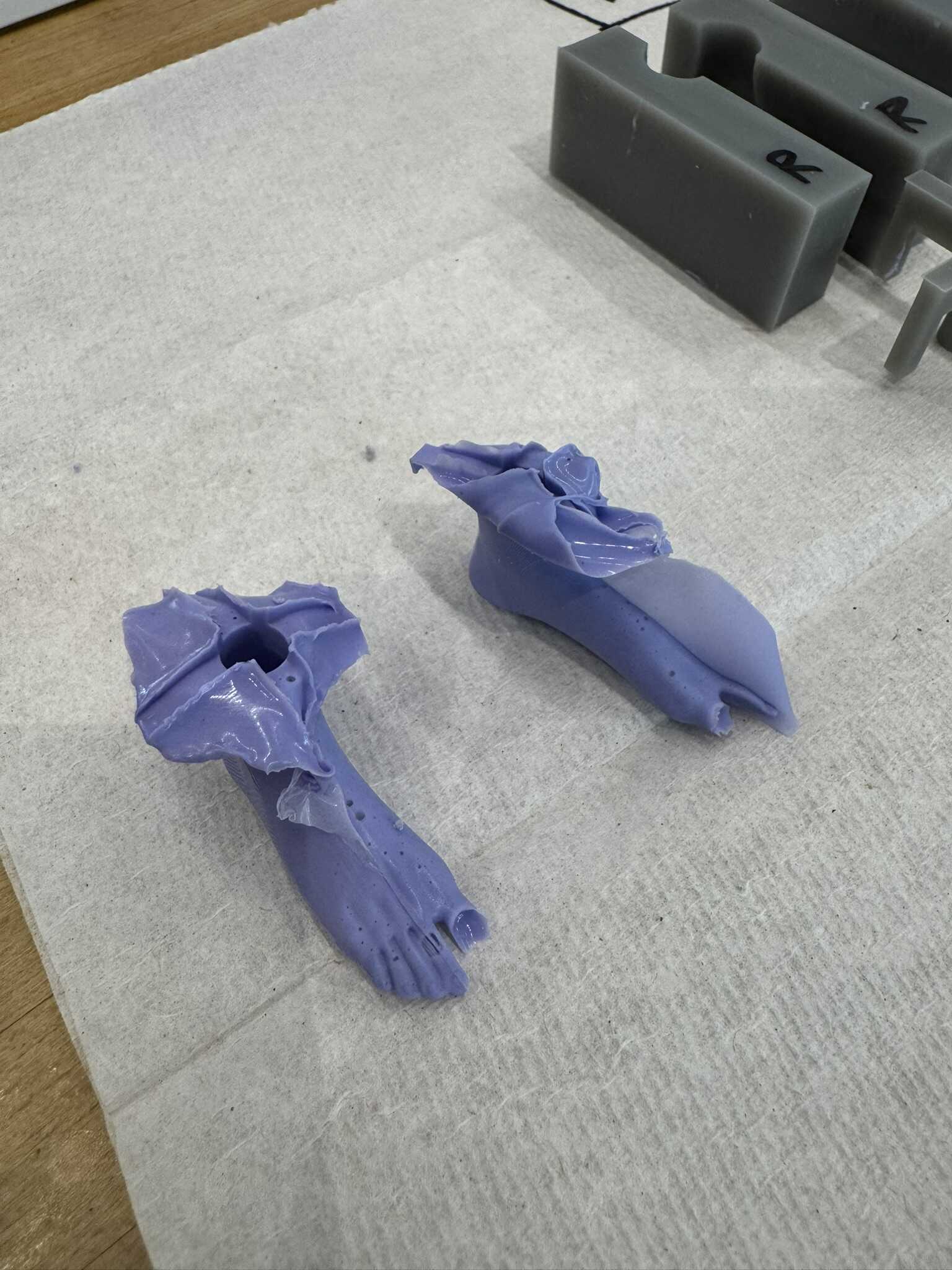

In parallel, I made progress on molding. In the interest of time, I decided not to sculpt my own boots, and moved forward with the STL from the internet (which I will make sure to credit in my final documentation). I started with the left boot. My computer could not handle converting it to a body, so I worked with the mesh directly in Fusion. I created a 1in x 2in x 0.85in prism around it, leaving just a little bit poking out the top, and then converted the prism to a mesh. I then subtracted the boot from it and cut it in 2 down its length (this left a small floating bit I couldn’t figure out how to remove). At this point, there was no way to mount it to the conrod, though. So, I added a third part to the mold - a 0.5in-long, 0.25in-diameter cylinder which hangs into the boot from above. The mount for the cylinder doubles as a mechanism to hold the three pieces of the mold together. Finally, I made a box to hold the molds from underneath.

I printed all four components on the Formlabs SLA printer using the Fast Model V1 material and a layer thickness of 0.100 mm. I found that with no tolerancing, the bottom box didn’t fit, but the top part did a fine job of holding the pieces together by itself. I mixed a little bit of OOMOO 30 and filled the mold. It was a little too viscous to go through the hole between the mold parts like I intended, so I filled the two parts first, and then pressed the cylinder in. I also found that the top holder alone wasn’t quite snug enough, so I added a clamp. The left boot seemed to be working well, so I repeated the same process for the right boot and left them both to cure overnight:

[12/11] Mechanism

The next morning, the print was complete.

The supports smoothed out the one important area, where the Delrin slides along the print, but were a huge pain to take off (especially out of the dowel hole). I will see if I’m able to add them selectively next time. If not, I will not use them. Once I got the supports off, I put together a new camshaft with the existing conrods. The bigger gap fixed both the friction and the alignment! The camshaft seemed to work really well!

Next, I wanted to find an alternative to the metal dowels, because I didn’t want to use so many. I decided to try to 3D print dowels. I printed a ranged of diameters, and found the one that fit best.

I printed them vertically, so that the print layers aligned. The one that fit best had the layers interlace, and made a really strong connection.

Next, I had to design a mount for the camshafts. I was originally using small bearings, and had a hard time designing a reliable connection. I talked to Jake again, and he recommended I use larger ones. He also recommended I place the bearing between the gear and the rest of the camshaft, but I ended up going with a simpler approach in the interest of time. I created a two-piece mount to attach the bearing to the sides of the box using three M3 bolts and nuts. I made sure that it only made contact with the outside part of the bearing. I then added a large cylindrical extrusion to the gear (with a hole for the axle to ease assembly).

I decreased the pitch of the conrods to make the mechanism fit in a 7-inch box

(keeping to my 14-inch carry-on constraint) and locked down the v3 camshaft.

I added six dowels and sliced the full set, keeping the supports for now. The whole print was estimated at five and a half hours, so I got started on printing the first one right away.

I spent the rest of my night focusing on my final report for 6.2540, so I had to stop there.

[12/11] Molding

That morning, the first set of molds was also done. There was a bit of a seamline, and the big toes were missing, but it was definitely good enough for this part of the project. And, they fit onto the conrods well! So, I decided not to iterate further in the interest of time. I started another pair and started mass-producing molds on the SLA (2 runs of 3 pairs each; I discovered that with the SLA, time is proportional to plate height!).

I also made a new holder, with more tolerance and holes for tension screws. I decided to print this on the MK4S to use SLA time for the molds.

3 more pairs of molds and one holder were done by the time the next pair of boots came out, so I got to molding. The printed holder did not work out great, because I didn’t account for the top part, which not only increases the total length, but was also above the tension point, which caused the molds to buckle when tightened.

By the time I was done pouring to OOMOO and figuring out the tension, the next set of molds was done as well! So, I started that one too. That was a total of seven pairs going at once. With the two pairs that I already fabricated, that’s only five rounds to get to exactly 72 boots. So, I decided to stop wasting resin. I didn’t have enough clamps, so I left some unclamped:

When I opened the molds up, some were not perfect:

But I determined it had more to do with me rushing against potting time, then it did with the clamps. So, for the next round, I went clampless for all 14 and left them overnight:

[12/12] Mechanism

In the morning, the first run of the v3 camshaft was done.

I struggled through the supports, but the results were great!

The bearing mechanism fit perfectly, and the camshaft rotated on it freely.

I kicked off two more sets. Unfortunately, one failed early on without me noticing. I let it finish for spare parts.

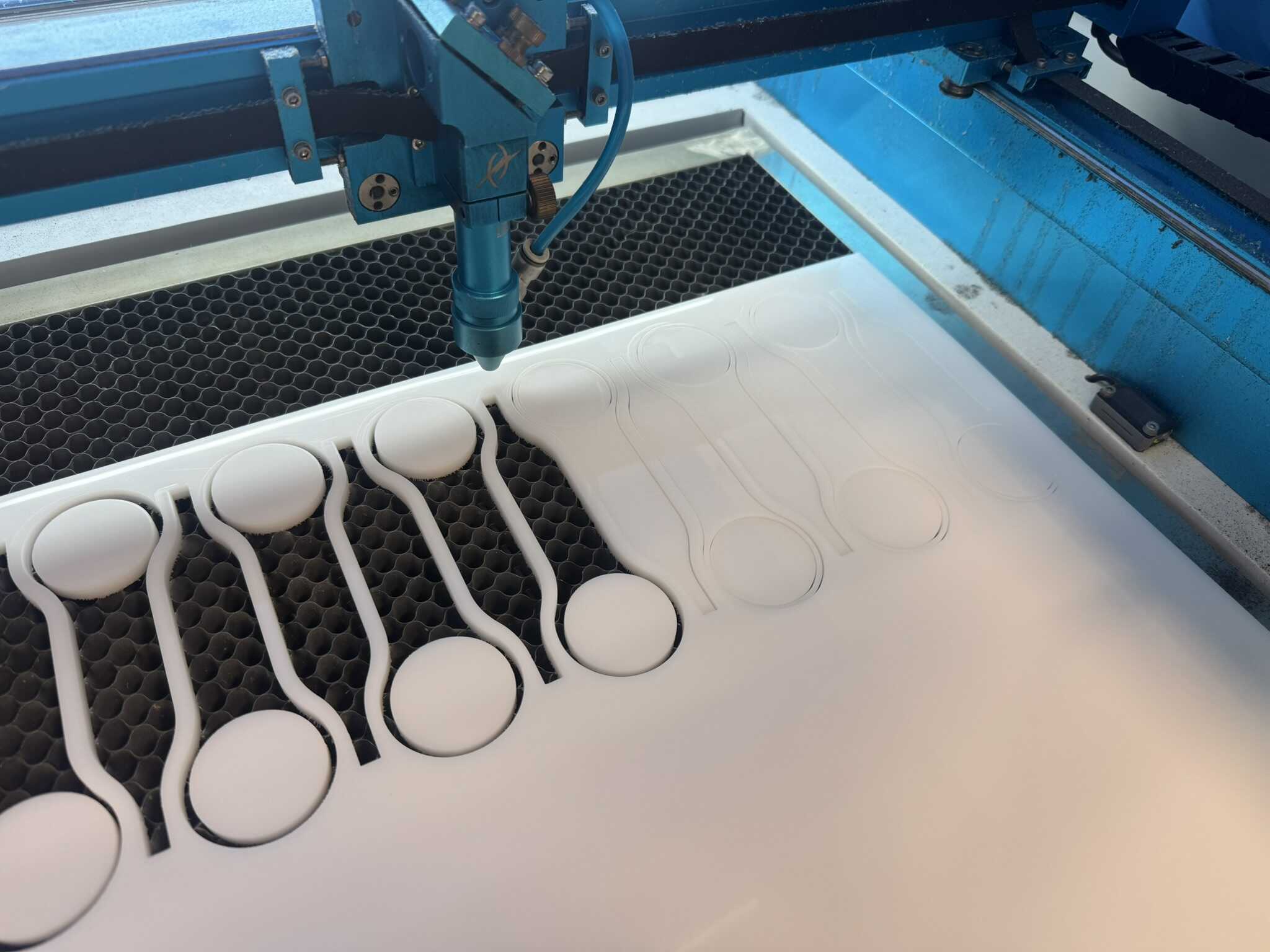

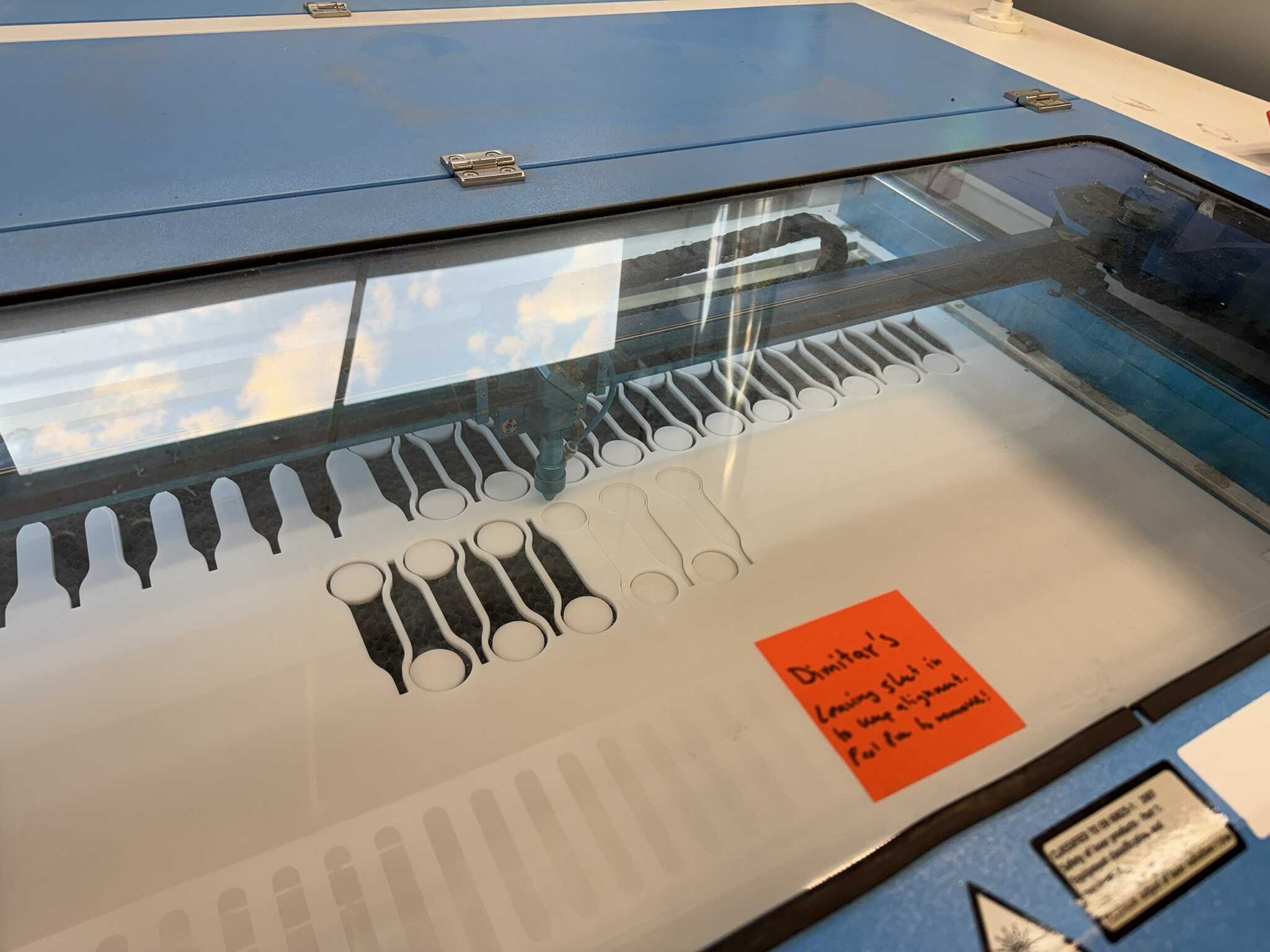

In parallel, I cut more conrods. I made a single cut file for 6 conrods nested together. It took 47 minutes.

I also figured out how much to offset the origin by on the laser cutter to nest subsequent sets nicely. I settled in at Mars and started mass producing them, taking out each set before starting the next, pausing only to load new 3D prints and new molds. The only issue I ran into was with the last conrod of the first row – it turns out that the Thunder Laser can’t cut all the way to the end of the bed.

I offset the next row by two to prevent this but keep the nesting.

By 4AM I had 6/12 sets of conrods cut (minus 1),

not counting the 6 I had used for the v2 assembly, which I chose to keep intact.

I also had a total of five v3 camshafts printed (including the suspect one).

I put together two complete assemblies using the first v3 print

and the non-failed v3 print of the second run:

I kicked off another two prints and went home.

[12/12] Molding

In the morning, this set turned out much better, as expected. I started the third full set, but one of the holders broke, so I had to add a clamp:

So, I designed new top holder, that did a better job of holding the molds together.

After the third set was done, I did the fourth with the new holders, which was much, much faster to set up.

Below are some pictures of me unmolding one boot from this set:

Before I left for the night, I started the fifth set as well.

[12/12] Stepper Motor

In addition to working on the mechanism and molding on Friday,

I also looked into the motor.

Since I decided to pivot to a stepper motor, I had to learn a little bit about how to control one.

I picked the NEMA-17 HS19-20004S1 and skimmed the datasheet for the DRV8428.

It turns out that it has a similar footprint to the DRV11873,

so I fabricated another copy of my breakout board from before and soldered one of the chips onto it.

I was originally excited about using the RP2354A for my board.

However, I was not able to figure out the laser engraving within my time box.

So, I need to pivot either to a RP2350 XIAO or to another micro.

The nRF24L01+ requires at least 5 pins and has 1 optional pin.

The DRV8428 requires a minimum of 2 pins and has 4 optional pins.

I need two DRV8428’s.

So, I need a minimum of 9 pins, but can make good use of up to 18 pins.

I decided not to sacrifice pins just to try to RP2350,

so I went with the RP2040 instead, in the form of a Raspberry Pi Pico.

The runner up was my favorite ATSAMD21E18,

but I wanted to have the option to use the PIOs on the RP series chips for the stepper motor controller.

I hooked up the HS19-20004S1 to the DRV8428 and the DRV8428 to the Pi Pico

as described in the DRV8428 datasheet.

I wrote a

simple test script

and got the motor spinning without a problem.

I used the 1/8th step and found that 83 microseconds was the minimum period that worked.

I confirmed that I can spin in both directions and that VREF changes the torque

(my laptop couldn’t handle values close to 3v3).

All of this testing was at 5V, but I plan to use it at a higher voltage.

Finally, I confirmed that the motor could drive the camshaft (without the pivot plate, which I chose not to re-print at the new pitch).

[12/13] Mechanism

In the morning, one of the two printers had run out of filament, so I replaced it. I had determined the previous day that despite my dowel test, I had an off-by-one error. So, while the second print was finishing up, I produced 18 correctly-sized dowels on the first printer. I also spent some time cleaning my desk to get organized. The first 6 camshafts are shown below:

Then, I modified the camshaft 3D print. I made four change:

- I fixed the dowel size

- I added support blocking under the dowel hole

- I increased the layer thickness

- I changed the supports to organic

I kicked off two prints with the new settings and went back to fabricating conrods. By midnight, I was done with all 12 sets in addition to the original one, as well as one spare set (of which one is spoken for).

The organic supports were not great. First of all, they required more space, so I had to print the bearing mounts separately. More critically, they did not leave as clean a surface when the came off. I put together one camshaft with them, and observed the friction was significantly higher. Despite having accumulated a few cuts on my hands already, I decided the normal supports were worth it, and reverted the change. Out of an abundance of caution, I also reverted the layer thickness. I kept the correct dowel size and the support blocking.

[12/13] Molding

In the morning, I started the final set of boots. In the evening, I started one extra set, as a set of spares.

[12/13] Radios

In addition to working on the mechanism and molding on Saturday, I also got the radios working. My work is documented documented on my Week 12 page.

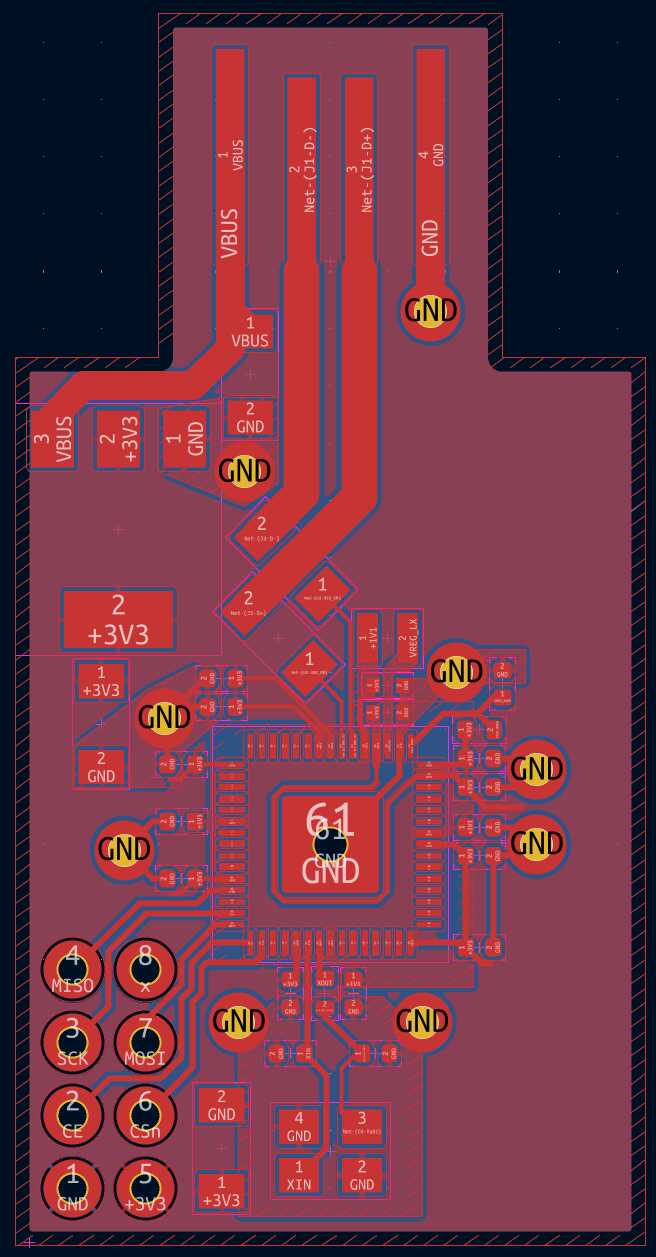

[12/14] PCB

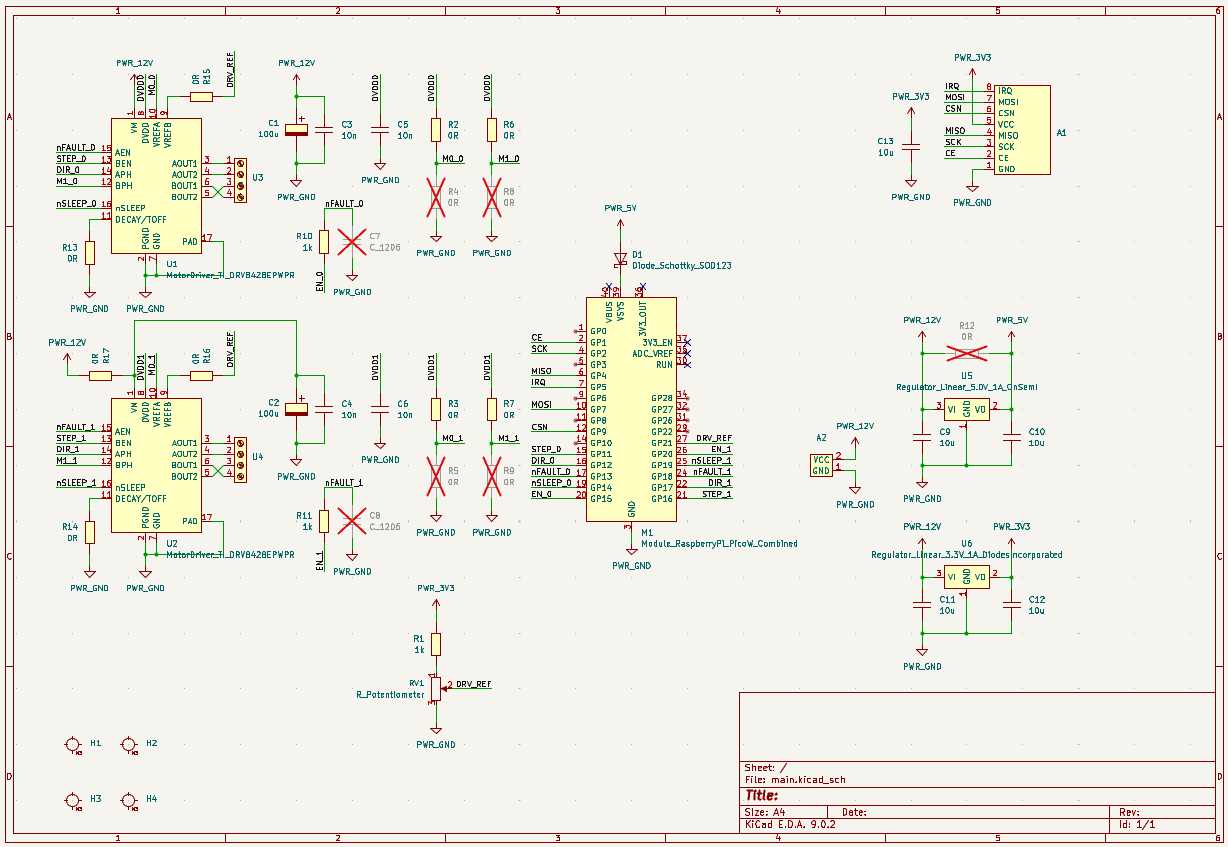

The first order of business on Sunday was designing and fabricating the main PCB. The schematic is shown below:

In addition to what I had prototyped,

I added input connections for nFAULT for the motor controllers and IRQ for the radio.

I also added DNP resistors for the micro-stepping setting pins.

I also added DRV_REF as an input, though truthfully it was mostly to help with routing.

I used screw terminals for the two stepper motors. I added a USB-C power extraction module, and linear regulators off that rail for all other devices. I also added a DNP bypass resistor to the 5V, since USB-C can supply 5V natively, and a diode to enable plugging in the Pico.

Then, I laid everything out:

I hooked up the IOs based on the layout. For the radio, this meant that I had to use non-default SPI pins, but was able to remap them in the sketch as follows:

SPI.setMISO(PIN_MISO);

SPI.setSCK(PIN_SCK);

SPI.setMOSI(PIN_MOSI);I fabricated the board on the Carvera:

The first turned out a little fuzzy, so I reran it. Then I stuffed it:

It worked as expected on the first try, in stark contrast to all my mechanical struggles.

[12/14] Firmware

I wrote an initial sketch by combining the stepper motor test code and the receiver test code.

I used atoi to parse serial data and used it as the delay directly, allowing for initial flexibility.

I used the same delay for both motors,

but I did encode direction in the sign of the number.

I mapped 0 to infinity.

This is a very crude approach, but is sufficient for integration. As excited as I was about the firmware, I made the decision to focus on integration next.

[12/14] Mini Box

For an initial integration test, I designed a mini box, that holds only one camshaft, not twelve. I used the same three “levels” I planned to use for the final:

- The bottom level is the legs below the pivots, with the ceiling being the pivots

- The middle level is the camshafts

- The top level is the PCB, battery, and motors, with belts fed through slots

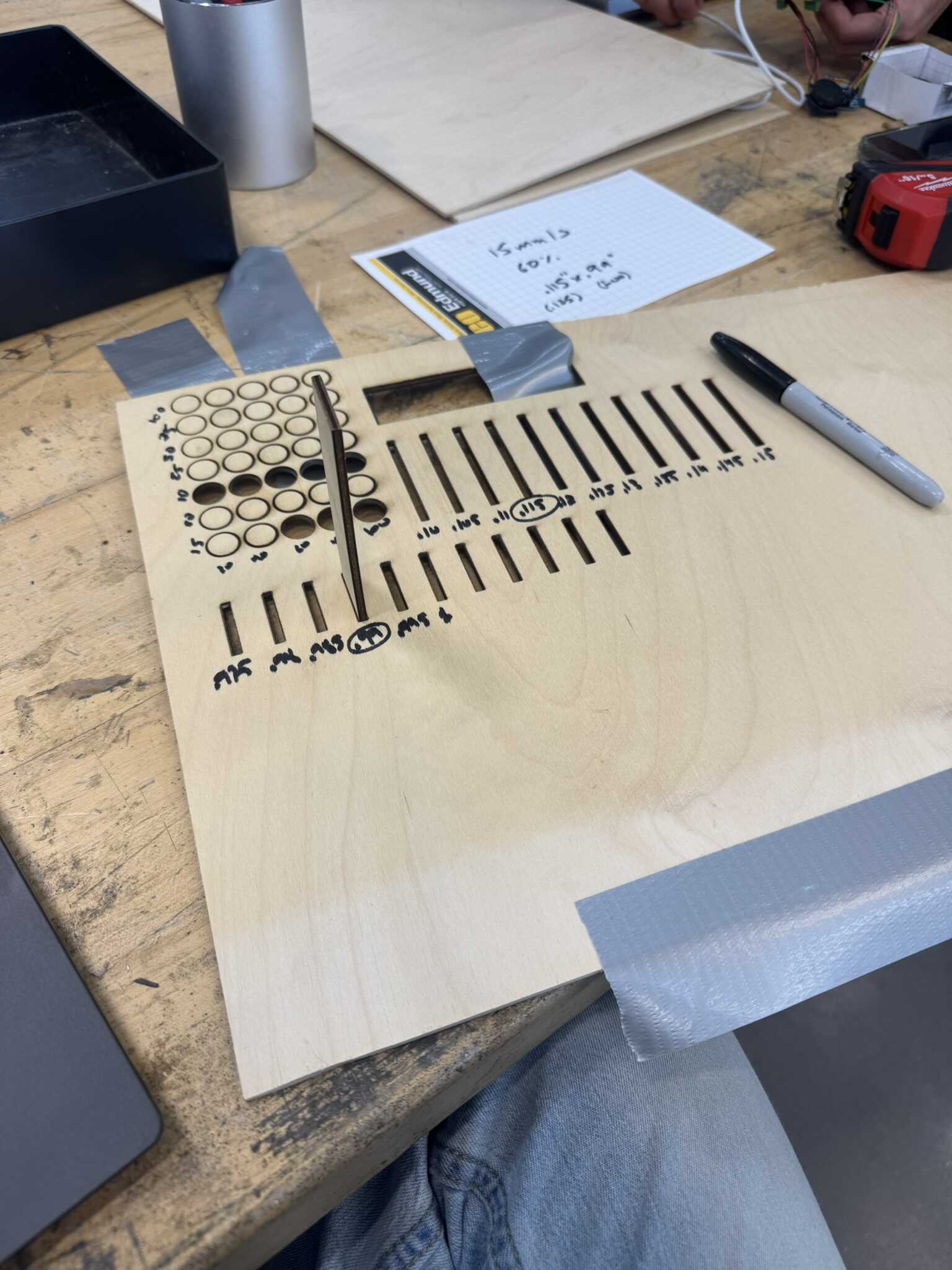

Finally, I circled back to my stock of wood. I started by doing the same cut test as I had on the Delrin. Again, the initial grid did not yield any results, buy the second grid revealed that a much faster cut time was sufficient:

I settled on 15mm/s and 60% power. Then, I tested the slot thickness necessary for a slot fit, in steps of .005in, finding .115in to fit most snugly:

Finally, I tested the length of the slot, again in steps of .005in, finding .99in to fit best for a nominal male with of 1in:

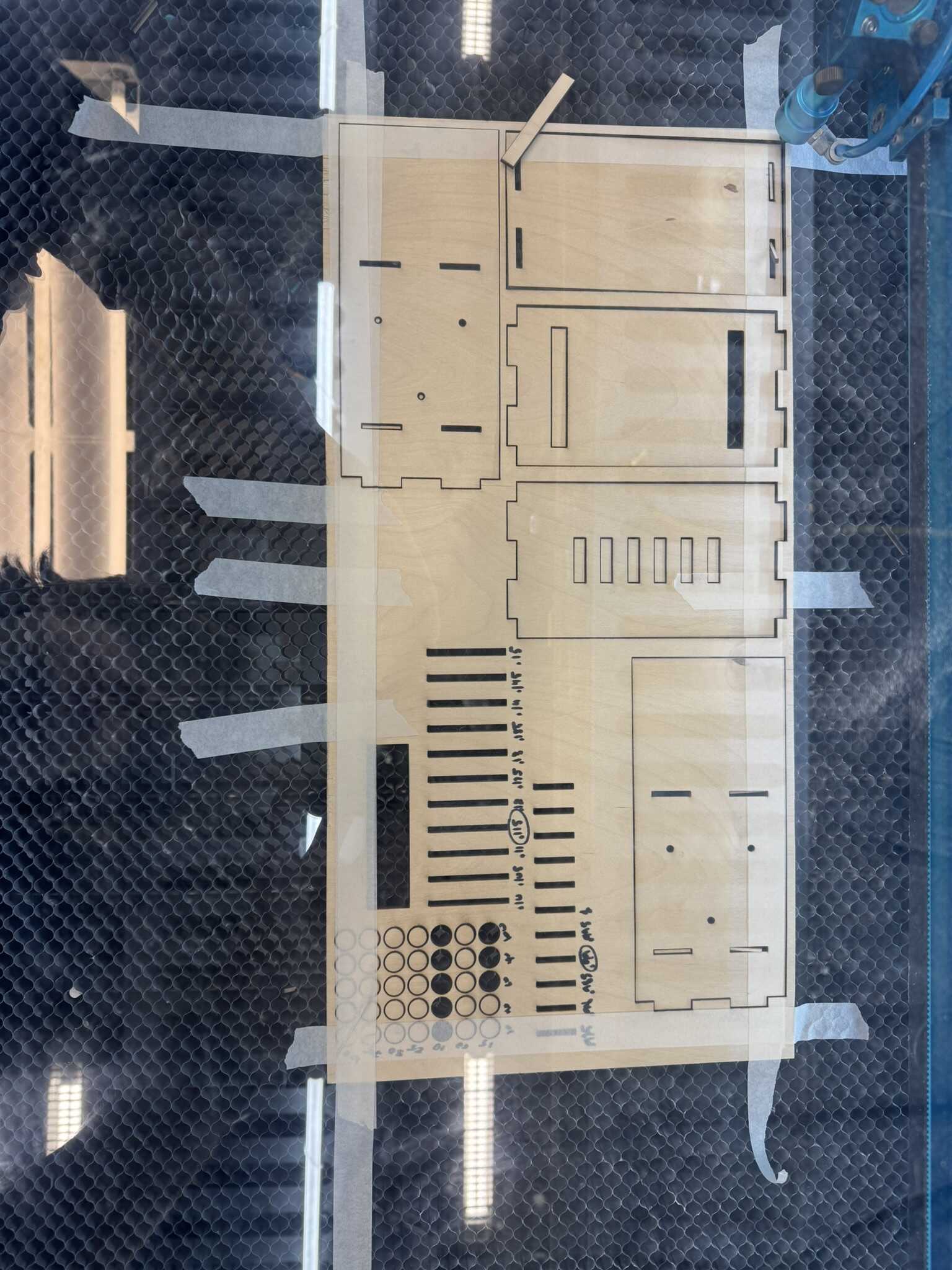

With this, I set the parameters in my design accordingly and cut the box:

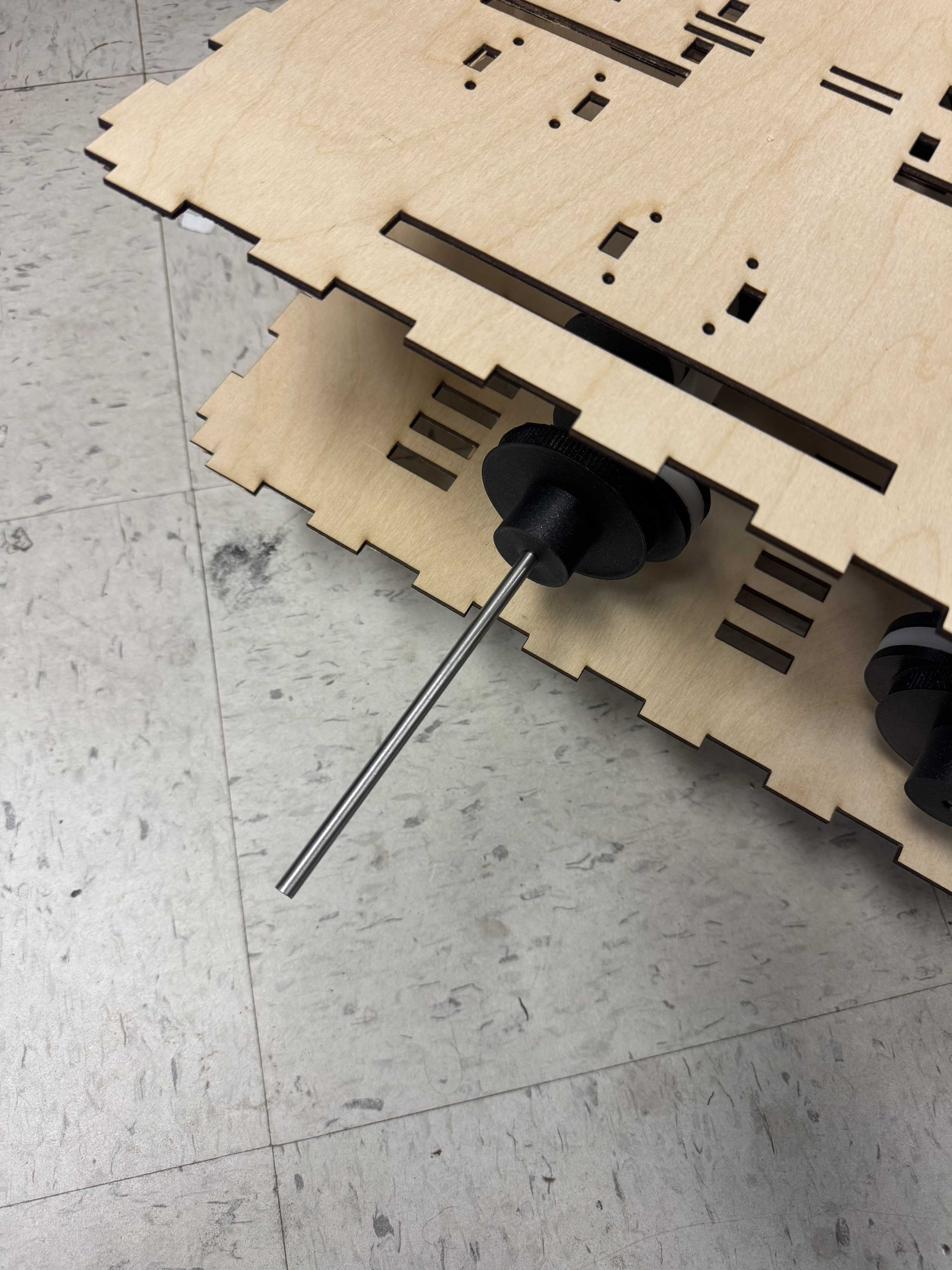

The design came together really easily. There were only two challenges. The first was the metal axle. I was hoping it wouldn’t be necessary, but this test proved that it was. However, I decided not to try to trim a steel rod to size at 2AM, so I drilled a hole in one of the sides instead (since this was just a prototype). The second challenge was tensioning the belt. I had a more sophisticated system worked out for the full design, but for the prototype, I placed a plank of wood on one side, and used a zip tie on the other side to create a lever over it. It worked great!

[12/15] Decision

At this point, demand-side time management had brought me to 2:30AM on Monday morning. I had three possible paths:

- Package up the prototype nicely

- Create a medium-sized box of 18 legs instead of 72 (which is also balanced)

- Create the full box of 72 legs

I had fabbed 72 of everything, so I of course went for the most ambitious of the three options.

[12/15] Large Box

Over the next 3 hours, I designed the full box.

I kept everything the same as the prototype, except that I took half an inch off the bottom level and add it it to the top level. Then I laser cut everything besides the top and sides, which took about an hour and a half:

The full sheet presented a problem, though. The laser did not go all the way through on the edges. I was able to cut some features out with a box cutter, but the most complex layer was impossible to cut and had to be run through the laser again. I decided to take a quick nap at this point and tried again, in the middle of the bed:

This worked well, so I cut the top cover while I started assembling.

I chose not to dismantle my mini box, just in case.

This left me with 6 assembled v3 camshafts, but one of those was the one I had printed with organic supports.

I tested it again and was still unhappy with the friction, so I got to work on assembling another camshaft.

This unfortunately did not go so well, and I had to make a quick pit stop for medical glue.

[12/15] Dongle PCB

Because I had found myself with some waiting time, I went back to redesign my dongle from a few days back.

I chose to pivot to the SAMD21 over the RP2354 in the interest of time,

and I decided to go with the XIAO version.

Hence,

dongle_samd_large.

The design was very simple and required only one jumper:

I was able to fabricate and stuff it quickly with no problem.

[12/15] Large Box Building

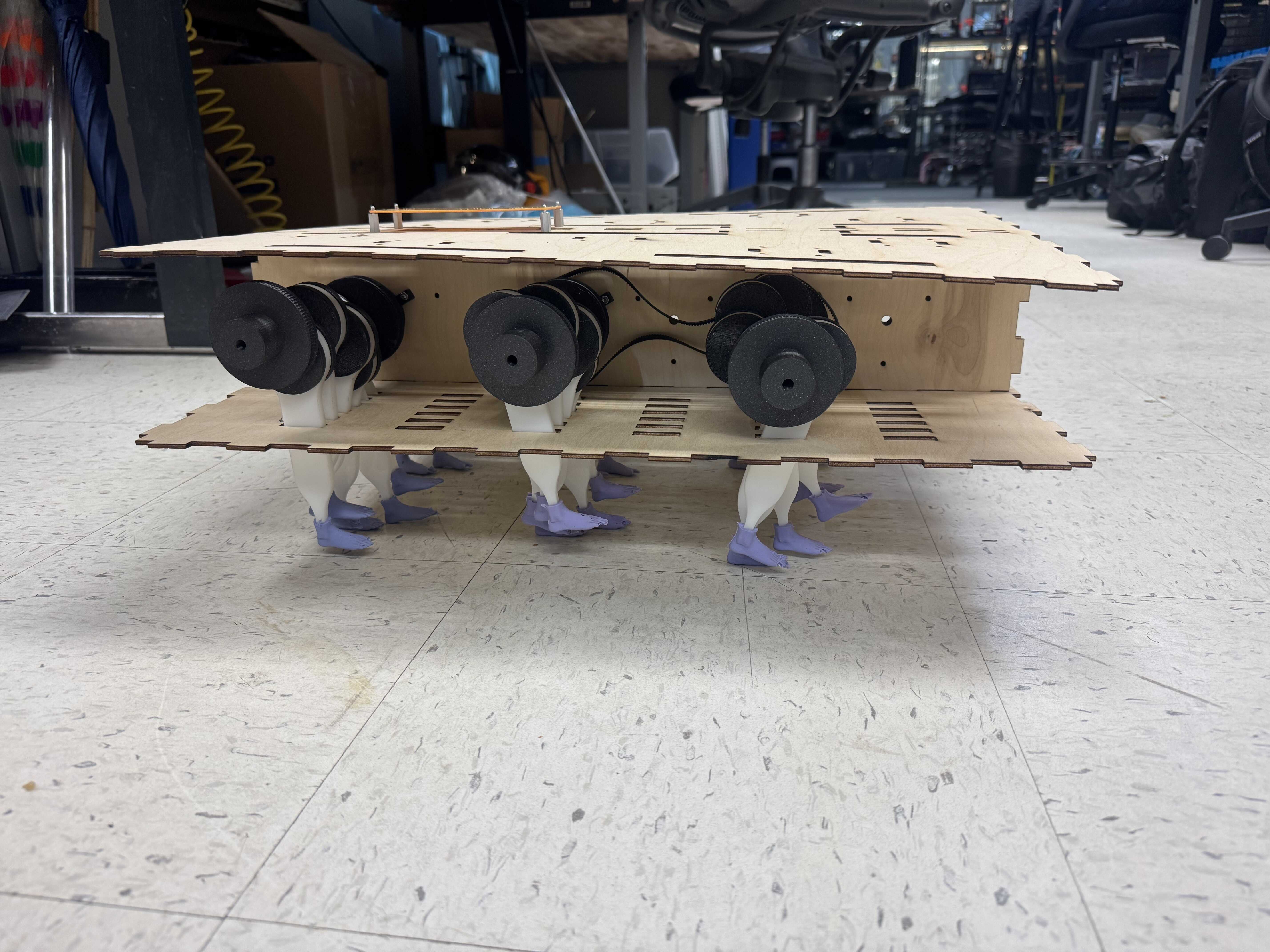

Going back to integration, I took a chance on the organic-support-printed camshaft, despite the friction. Unfortunately, once I assembled it, I could not push the axle through to the other side, as I had done with the other camshafts. With this, I gave up and moved the PCB back to my prototype for demo (and attached the unstuffed copy of the main PCB to the large box’s PCB mounting points). Some pictures of the final state of the large box are below:

All parts have been fabricated, and the integration if fairly close, so I hope to complete it soon. I will update this page once I do.

[12/16] Interface

I wrote a simple interface to control the luggage using the existing dongle design. My work is documented documented on my Week 13 page.

Questions

What does it do? It walks around.

Who’s done what beforehand? I didn’t find projects that have done this before. In 2013, I made a Strandbeest, which is somewhat similar, but uses a very different mechanism.

What sources did you use? The most important source I used was Jake Read.

What did you design? I designed the overall system. Mechanically, I designed the camshaft and conrod mechanism, the mounts, and the box (all through various iterations). I also designed the molds for the boots. I designed an assembly process for the camshafts and a molding process for the molds. Electrically, I designed the circuit and the PCB for both the on-board electronics and the remote “dongle”. Finally, I designed firmware for both, and a software interface for the latter.

What materials and components were used? The camshafts were made of PLA. The conrods were made of Delrin. The box was made of wood. The PCBs were made of FR1. The boots were made of OOMOO. The molds for the boots were made of resin. The axles were made of steel.

Where did they come from?

- The HTMAA/CBA inventory

- The machine week kit (which wasn’t fully consumed)

- My personal inventory at home

What parts and systems were made? All parts and systems were made except:

- Bearings

- GT2 Belts

- Stepper motors

- Raspberry Pi Pico module

- XIAO-SAMD21 module

nRF24L01+breakout board- USB-C Power Bank

What tools and processes were used?

- FDM 3D printing (Prusa MK4S)

- SLA 3D printing (Formlabs)

- Laser cutting, Delrin (Thunder Laser)

- Laser cutting, wood (Thunder Laser)

- Molding

- PCB Milling (Carvera)

- PCB hand-soldering

- Mechanical hand-assembly

What questions were answered? For me, the biggest unknown going in was if the friction on the camshaft without bearings would be too high. It did not seem to be.

What worked? What didn’t? The camshaft mechanism worked well, as did the electronics and firmware. Assembly did not work so well (or at least took very long).

How was it evaluated? I evaluated it by whether it could walk. Because I didn’t assemble the full version, the prototype could only walk while being held upright. So, partially.

What are the implications? Many little feet may be a impractical but functional alternative to wheels.

Sources

- Sketch, main: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/blob/main/firmware/main/main.ino

- Sketch, transmitter: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/blob/main/firmware/simple_transmitter/simple_transmitter.ino

- Sketch, receiver test: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/blob/main/firmware/simple_receiver/simple_receiver.ino

- Sketch, stepper motor test: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/blob/main/firmware/simple_stepper_control/simple_stepper_control.ino

- Python script, interface: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/blob/main/software/luggage-controller/main.py

- KiCad Project, main: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/tree/main/hardware/main

- KiCad Project, first dongle: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/tree/main/hardware/dongle_medium

- KiCad Project, second dongle: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/the-luggage/-/tree/main/hardware/dongle_samd_large

- KiCad Project, PWP0016A breakout: https://gitlab.cba.mit.edu/dimitar/kitchen-sink/-/tree/main/breakout_PWP0016A

- CAD, left foot (from internet): https://a360.co/4j6FoDk

- CAD, right foot (from internet): https://a360.co/4sqPCD5

- CAD, wheel: https://a360.co/4atVEvY

- CAD, bearing: https://a360.co/4j9iI5z

- CAD, conrod: https://a360.co/4j9cdzD

- CAD, manual_pulley: https://a360.co/4aoOgSA

- CAD, pulley: https://a360.co/49azPzm

- CAD, test_axle: https://a360.co/4p0r7cF

- CAD, mini_box: https://a360.co/496RY11

- CAD, box: https://a360.co/4s880QR

- CAD, plate: https://a360.co/4paKakx

- CAD, assy_leg_left: https://a360.co/4p5PjdG

- CAD, assy_row_left: https://a360.co/3MYRJxr

- CAD, assy_leg_right: https://a360.co/45jy1Ti

- CAD, assy_row_right: https://a360.co/4pN7yFT

- CAD, assy_main: https://a360.co/4ql9Dc2

- CAD, mold_left: https://a360.co/4qmevhh

- CAD, assy_mold_left: https://a360.co/4jfiXMy

- CAD, mold_right: https://a360.co/45cXFsV

- CAD, conrod_inner_test: https://a360.co/44F7uje

- CAD, second_conrod: https://a360.co/44GOEbs

- CAD, concept_conrod: https://a360.co/4jt5EIx

- CAD, bottom_plate_sketch: https://a360.co/45l7xAO

- CAD, mold_holder: https://a360.co/4qrDFet

- CAD, dowel_test: https://a360.co/4qpNHwE

- CAD, camshaft_end: https://a360.co/4j9x7OV

- CAD, camshaft_section: https://a360.co/44DAlo0

- CAD, mold_top: https://a360.co/3Lf3EXt

- CAD, dowel: https://a360.co/4au0NV0

- CAD, six_conrods: https://a360.co/4pPq8NR

- CAD, wood_test: https://a360.co/4atpaSG

- CAD, bearing_mount: https://a360.co/49jSBW9

- CAD, mini_box: https://a360.co/3KGv5JG

- CAD, second_box: https://a360.co/4p7HZOP

- CAD, assy_camshaft: https://a360.co/4p7DSlU