How to Make Something Big

Workflow

Design

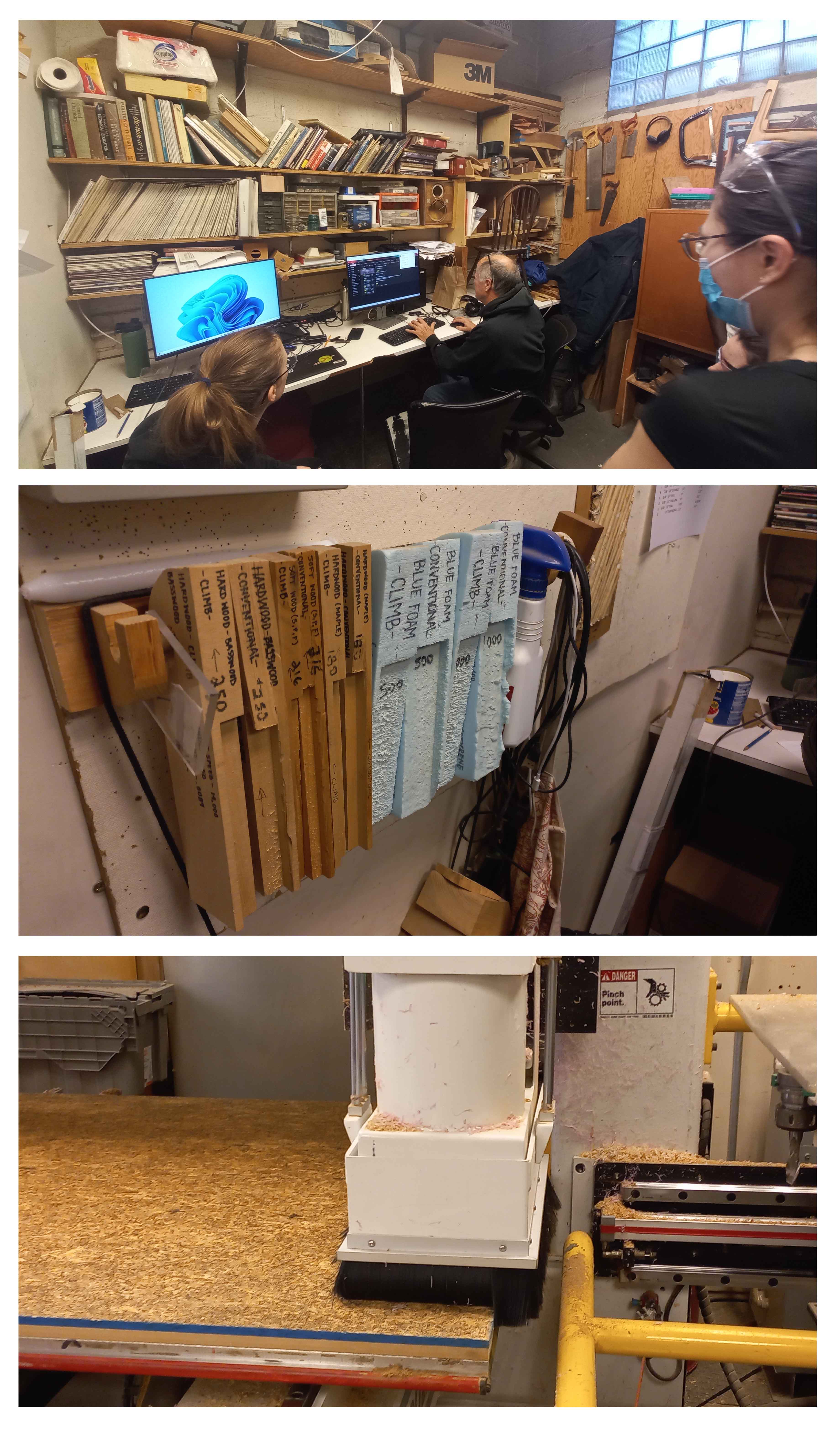

This week we were tasked to make something big using the CNC machine at N51. During the group project we ran several tutorials understanding how to set up MasterCAM and run the large CNC machine. Essentially, I surmised that this week’s task ran on the same principles as the laser cutting week. We needed to take into account how the parts in our design were going to it together. Defining the depth of the timber panels was also going to be intrinsic to the successful assemblage of the final product.

Initially I wanted to make a small children bicycle for adults. I wanted to prototype this in a group with Sergio. We eventually decided to go into this week as individual projects. I changed focus and wanted to make a large flip phone which I could use as a lap-laptop workspace. I ran some ideas in my head and in my sketchbook. It was going to be too much effort for a single weeks work. I decided to adapt the design to become even more useless.

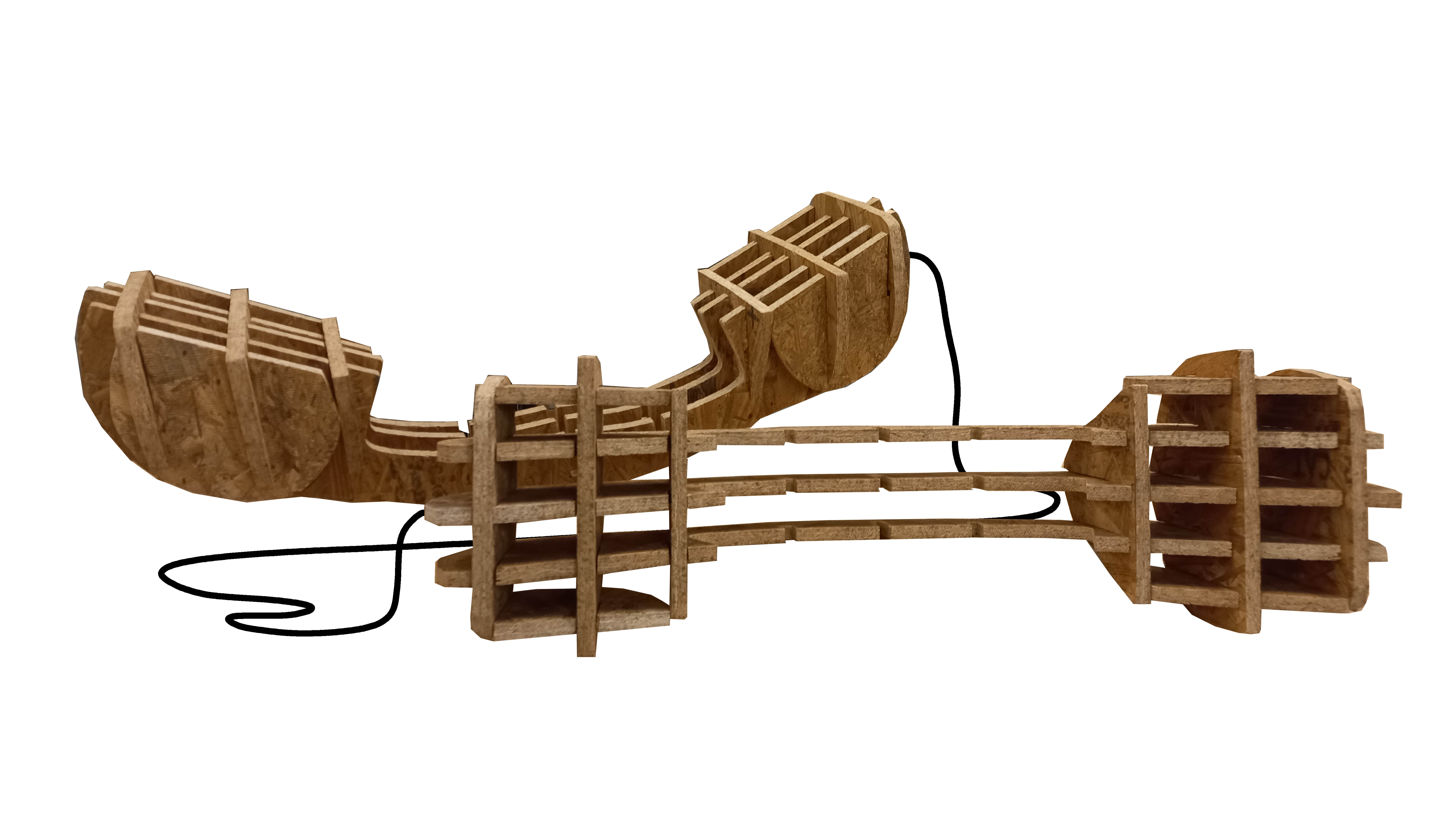

I was inspired by an old rotary phone which we had at our house, the retro revival movement in handheld technology, the rise of the dumb phone and those old tin can - string communication prototype – I decided to make a massive performative cellphone cover in the shape of an old rotary phone.

I started by finding a 3D model online. My preferred site is SketchFAB (it offers quite a substantial and easy to use library of 3D objects to download and use). Initially my plan was to start by scaling the phone model and then drawing the panels at appropriate intervals so that it could be booleaned.

After a few attempts, I decided to Boolean the phone and the panels first, and individually export them after they have been cut and boolened. Essentially the panels would be made and cut to account for the slots, then the exterior Boolean would be made. This would significantly speed up the proceedings and meant that I didn’t have to calculate the slits in the panels post Boolean.

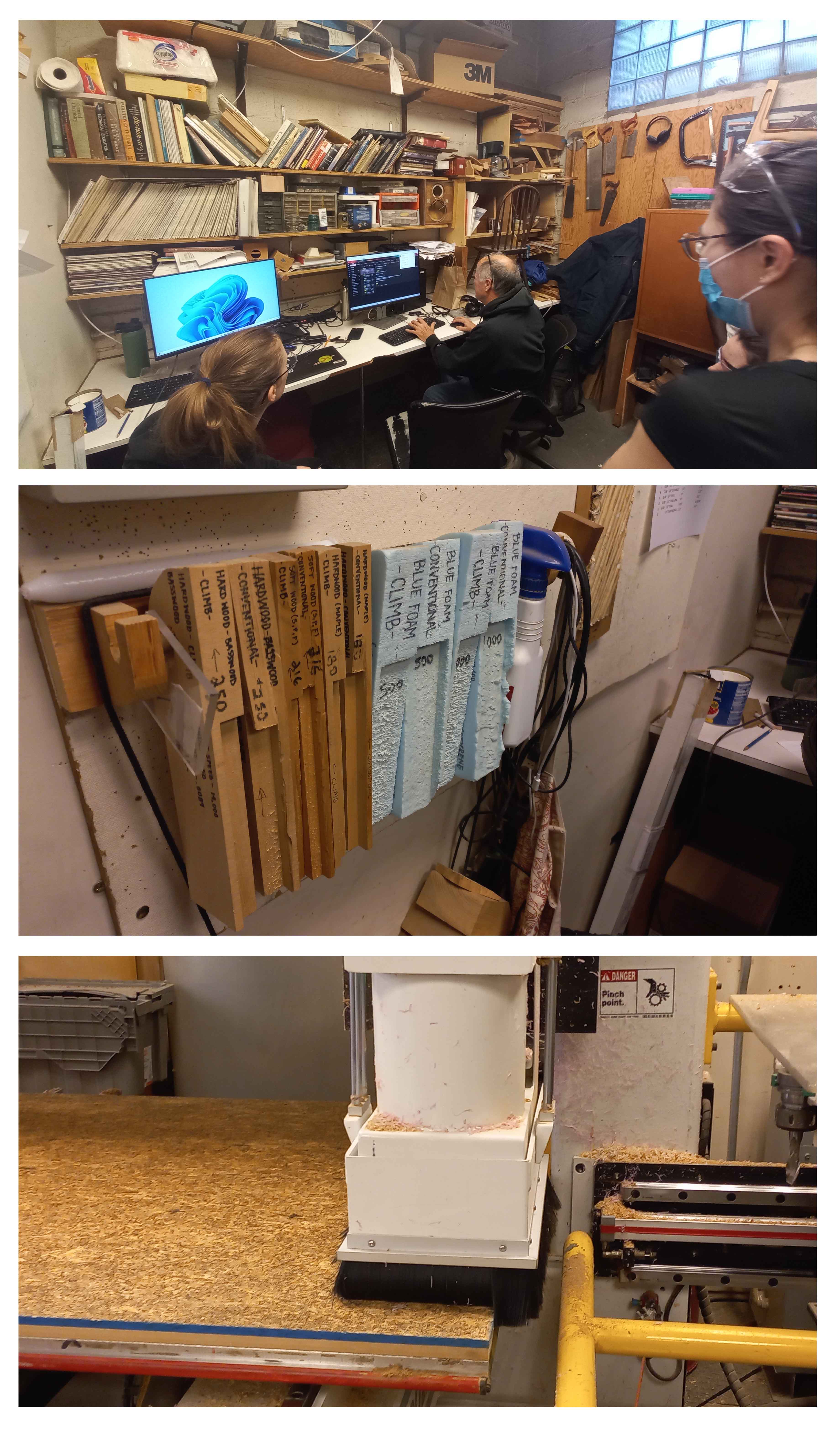

To make sure I didn’t make any unnecessary mistakes, I labeled each panel and generated a grid layout showing each joint as a consequence of its column and row. I placed the extracted panel sizings on a 4ft x 8ft block to see if the required number of panels need resizing or more efficient placement. Jen helped me with this step and suggested a thicker onion skin underneath the more fragile and smaller pieces.

One of the interesting and more challenging differences which this week has over the laser cutting week is that each batch and type of timber has different challenges. For example hardwood takes longer to mill but is stronger than composite materials like OSB (Oriented strand board). OSB is much cheaper than hardwood and depending on the needs of the project you might not need to spend much money on more expensive materials.

Manufacturing/Maing

Because of a mix-up and the ONSRUD machine breaking during the initial How to make something big week, I had postponed the actual making of the project. When I returned, I finished the project. I had already checked that the file was set up correctly and Jen had helped me to send it accordingly and accurately. Chris helped me to start everything back up and I milled it. Before starting, in the back of my mind, I was thinking If the drawings were still reflective of the actual board which we would be using, But I chose to ignore my instincts.

In the end this backfired because as I was sanding the onionskin off of the pieces, I came to the realization that neither of the slots were big enough. I had to decide whether I was going to redraw and recut or just try and adapt the existing pieces. I wanted to save on material and machine running cost – perhaps because I was from South Africa, and you have to be quite resourceful and reduce waste because things are expensive and not so readily available. Or maybe – or perhaps because I wasn’t in the mood nor had time. It was probably both.

I decided to push onward and modify the pieces until I could start fitting them together. The first phone was cut with more care and made to fit as I went along, and it kept together a lot better than the second one. To my detriment, I was also more stubborn and wasted a lot of my own time because I didn’t want to refer bac to my schematics, so I ended up speaking much more time than I should have.

I had several machine faults apart from the ONSRUD malfunctioning. The bandsaw’s blade came off of the track as I had 3 cuts left, and Chris helped me to get it back to functioning. Also, the extraction tube attached to the ONSRUD’s milling head also dislodged and Chris fixed it back up.